This summer, three at-risk research partners from Afghanistan were evacuated after Kabul was captured by the Taliban in August 2021.

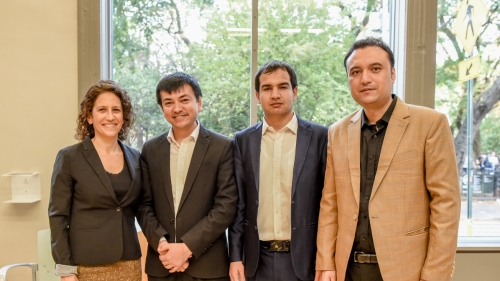

All three now study and work at NYU Steinhardt after a complicated process that took nearly a year and was the result of a collaboration between NYU Steinhardt’s International Education program, the Office of the Provost, Scholars at Risk, and a network of offices across the School and New York University.

Long-Term Education Research in Afghanistan

Since 2005, Dana Burde, associate professor and director of international education, has been conducting research on supporting education amid conflict in Afghanistan. One of her long-term engagements began in 2013, when she received funding for a research project called Assessment of Learning Outcomes and Social Effects of Community-Based Education in Afghanistan (ALSE) and worked with NYU to establish a non-governmental organization (NGO) called NYU Afghanistan.

“ALSE looked at what happens when you create small, community-run schools in remote and rural villages, considering questions like whether children attend and whether boys and girls learn at the same rates,” says Burde. The study showed that supporting community-based education eliminated gender disparity in enrollment and significantly narrowed the achievement gap.

ALSE was one of several programs across the country funded by US taxpayer money through 20 years of US intervention in Afghanistan, seeking to expand universal access to education across the country. ALSE also worked to study the institutionalization of these programs by assessing collaboration between communities and governments. To carry out the work, Burde and colleagues hired around 10 Afghan staff.

“Those staff were phenomenal, and we established strong relationships with them – some of them stayed through the project’s close in 2019, after which point a few kept very part-time roles to maintain the NGO,” says Burde. “When the Taliban takeover began in 2021, our staff and friends in Afghanistan were in serious danger because of their work with us.”

After garnering support from NYU leadership, Burde set the wheels in motion for NYU to leverage its power to help save lives.

When Kabul Fell

With a bachelor’s degree in political science, a master’s degree in business administration, and years of experience in the research field, Hamidullah Gharibzada joined NYU Afghanistan in 2015 as research associate. When ALSE ended, he became president of the NGO to maintain its presence in the country, while also working in Kabul as a senior monitoring and evaluation specialist at one of the international NGOs working on USAID projects in Kabul.

“On the morning of August 15, 2021, I went into my office early and everything was mixed up – all of the foreigners had been evacuated, and we were told to clean out our desks and destroy everything that had people’s names on it,” says Gharibzada.

In addition to the paperwork at his current job, Gharibzada also had all the old ALSE paperwork archived at his home – which also had to be destroyed for safety.

“If the Taliban found any evidence of work with an American organization, it would have been the end for me,” says Gharibzada. “My wife and mother and I spent hours tearing names out of the paperwork from NYU Afghanistan and putting them into plastic bags. We would carry the bags out to different places to dump the bits of paper so that nothing was traceable or identifiable.”

Through a colleague, Gharibzada reached out to Burde and asked what to do with everything else – printers, scanners, satellite phones. She told him to dump it all. Gharibzada smashed everything into small pieces, dropping the satellite phone into the sewer of his house; at this point it was 4 p.m. and the Taliban was all over the city.

Mohammad Jawed Nazari was a research officer with NYU Afghanistan for the duration of ALSE, working closely with key staff at the Ministry of Education, provincial education directors, school management counselors, teachers, community leaders, and students. After ALSE ended, Nazari worked as senior education research specialist with another US-based institution: the USAID-funded Afghan Children Read Project, implemented by Creative International Associates. He also worked as a researcher in Afghanistan for other organizations such as the Asian Development Bank and Afghanistan Institute for Civil Society.

“On August 15, 2021, I was at my office at the Afghanistan Institute for Civil Society, where I was a research and policy engagement manager,” says Nazari. “I received a message from my family that the Taliban had entered Kabul. In the office, we were told to leave as quickly as possible and go to a safe place.”

Nazari’s one-hour drive home took four hours that day because of the number of people running through the streets.

I had been seriously considering applying to the PhD in International Education, and Dana [Burde] had encouraged me to apply. When the government fell, I reached out to Dana and asked for her support because our lives were in danger.

“The whole system collapsed overnight,” he says. “Because of my strong working relationships with US agencies, I knew that if the Taliban found out who I was working for, they would come for me. So, I deactivated my social media, deleted the contacts for all US colleagues, and tore up documents that related me to the US. Then I changed my house, contacted Dana, and told her we were in a grave danger and didn’t know what might happen.”

After his time working as a research officer for NYU Afghanistan, Abdul Hamid Hatsaandh had come to the United States as a Fulbright Scholar for a master’s in international education policy at Harvard University. After earning his degree, he returned to Afghanistan in 2019 to work for several years as a fulfillment of his Fulbright. He was serving as an educational research manager for Afghan Children Read, a US-government-funded project implemented by the US-based Creative Associates International Inc., when the Taliban took control.

“When Kabul fell, it was a terrifying time,” says Hatsaandh. “For anyone with connections to US education and government-funded projects, we knew that if the Taliban found out who we had been working for, we would be in big trouble. I was living in hiding.”

Hatsaandh diverted the Taliban’s door-to-door search of his neighborhood by taking his wife and kids to a friend’s home in an area that was already searched, giving his own house key to his neighbor.

“I told my neighbor to tell the searching group that the apartment was his brother’s and that he had gone visiting his parents,” says Hatsaandh. “I feel really fortunate that the searching team did not find out about me that day.”

Hatsaandh had also deleted from his phone and computer all the contact names and numbers of US-based colleagues, as well as his classmates at Harvard. He stayed in communication with Burde, but he would dial and then delete her number every time he contacted her so it wouldn’t be found if he got caught and his phone was searched.

“I had been seriously considering applying to the PhD in International Education, and Dana had encouraged me to apply,” says Hatsaandh, who had a wife and three young children – including a newborn baby – at the time. “When the government fell, I reached out to Dana and asked for her support because our lives were in danger.”

A New Chapter Begins

Burde had begun making connections for Gharibzada, Nazari, and Hatsaandh to figure out how to get them to the US and safety. After trying many different pathways, the network of supporters throughout NYU were able to organize evacuation efforts for all three – in slightly different ways.

For Nazari and Hatsaandh, Burde worked closely with Steinhardt Graduate Admissions, the Office of Doctoral Studies, and the Office of Global Services with additional guidance from Scholars at Risk to put together packages for J-1 visa applications for students and scholars.

“Studying a PhD was my lifetime dream since I began working in education in 2015,” says Nazari, who is on track to graduate in 2027. “I’ve worked for a long time in international education, especially in emergency and conflict contexts. The atrocity in Afghanistan was a catalyst for me thinking about this seriously as a life-saving option.”

I really thank Dana [Burde] and everyone at NYU for supporting us and providing us with what was both a life-changing and life-saving opportunity. This was not a one-person job. It was an honor to work with NYU back then on ALSE, and I’m honored again to have found these wonderful people who helped provide me with this opportunity to work together again in different circumstances.

Nazari was accepted into the PhD program and was able to fly to Islamabad in March, where he and his wife, who had been working as an administrative officer with the Ministry of Interior Affairs in Afghanistan before the collapse, lived for three months before arriving in New York City on May 26, 2022. His mother, sister, brothers, and other family members are still in Afghanistan.

After eight months in Afghanistan with the Taliban in charge, Hatsaandh was also able to fly with his family to Pakistan, where they lived for several tense months while they waited for their visas to come through.

“If our visas to the US were denied, what were we going to do?” says Hatsaandh. “We could only stay in Pakistan for two months straight, even though our visas were valid for a year. Back then, everyone in Afghanistan knew that traveling to Pakistan meant fleeing from the Taliban, so going back was not an option anymore.”

Thankfully, the visa process was completed, and Hatsaandh is now undertaking his PhD with an interest in understanding the role of educational technology in providing access to education in areas that are affected by major disruptions, such as natural disasters or war. His two older children are in elementary school, and his wife is learning English through online classes at the International Rescue Committee.

Gharibzada also had a long road between the fall of the government and his arrival in New York. His employer was able to arrange a small, twenty-seat evacuation flight in September to get him and his family to safety in Pakistan. He, his wife, daughter, and two boys lived there for nine months while he worked with NYU on his H-1B visa application to the US, which would allow him to come to NYU as an employee.

When his visa was finally approved after an initial rejection, Gharibzada’s flight to JFK Airport arrived on June 26, 2022. He is now an associate research scientist working with Burde to conduct follow-up work on their previous education research. His mother remains in Afghanistan.

“I really thank Dana and everyone at NYU for supporting us and providing us with what was both a life-changing and life-saving opportunity,” says Nazari. “This was not a one-person job. It was an honor to work with NYU back then on ALSE, and I’m honored again to have found these wonderful people who helped provide me with this opportunity to work together again in different circumstances.”

On November 4, 2022, Steinhardt hosted a celebratory event to honor the journey of the three scholars and the hard work of the many people who contributed to their arrival in New York. Less than 24 hours later, Gharibzada and his wife celebrated the birth of their fourth child.

Related Articles

International Education Students Make a Social Impact with CAIR

IE students help CAIR Philadelphia win grant support.

Education in Afghanistan: How to Move Forward

Amid Afghanistan's significant humanitarian crisis, the Taliban continue to ban secondary education for girls in most provinces. As foreign governments contemplate if and how to engage with the Taliban to support the population, it is essential that they understand what Afghans themselves think of the Taliban’s edicts, particularly with regard to girls’ education.

Professor Teboho Moja Invited to Speak at the World Science Forum in Cape Town, South Africa

The Forum included representatives from leading global science organizations and explored the role of science in advancing social justice.