A new style of ‘memory activism’ has shifted focus from memory as a force for national unity to memory as a critique of national myth

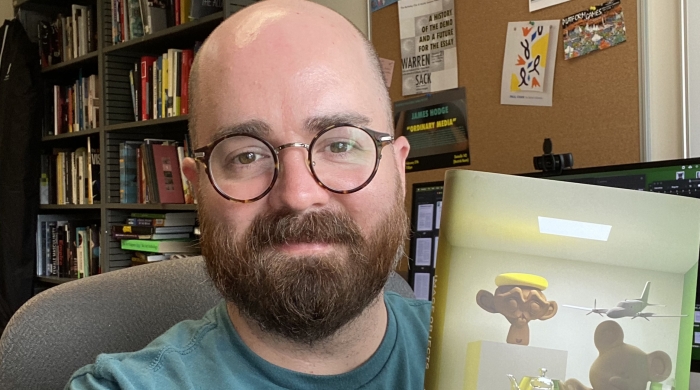

Marita Sturken

The United States has a memory problem. Whether through conflicts over statues or bills attempting to ban critical race theory in classrooms, how we tell the American story is under constant debate in our nation’s public spaces, schools, and legislatures. As these battles play out among increasingly polarized factions, new questions about memory, identity, and culture emerge as the US continues to grapple with an ever-mounting COVID-19 death toll, police brutality toward people of color, and anti-Asian hate crimes, among many other issues.

According to NYU Steinhardt Professor Marita Sturken, these recent events marked a “turning point in the priorities of the nation that demonstrated, a full generation after 9/11, that its primary sites of conflict and contention are internal rather than external.” Among the internal conflicts in the US, she notes deep political factionalism, domestic terrorism, a national reckoning on race relations, and the deep divisions created by the pandemic. These contested issues stand in contrast to the wide public support for the US wars in Afghanistan and Iraq during the post-9/11 era.

In her recently published book, Terrorism in American Memory: Memorials, Museums, and Architecture in the Post-9/11 Era (NYU Press 2022). Sturken explores the ways that the September 11 terror attacks catalyzed two decades of frenzied nationalism that shaped the way the US promoted patriotism in memorials of the period.

NYU News spoke to Sturken about her critiques of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum and other 9/11 memorials, and how the process of commemoration is being approached differently in this new era.

What inspired this book?

I have been writing for some time about the memory of 9/11 and the crazy politics of it in New York in particular. As the pandemic hit, and it became clear that the post-9/11 era had ended, the full argument of the book came together, with the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, forming a bookend to 9/11 memory and pointing to new forms of memory activism. While the nationalistic 9/11 memory allows the US to appear an innocent victim, the lynching memorial demands a reckoning with the nation’s guilt. A primary aim of the book is thus to situate the history of terrorism in the US, not simply as a force visited upon us from foreign entities, but as a key element of the history of the nation, evident in the long history of racial terrorism in the form of lynching and now clearly on view in the rise of domestic terrorism.

In the book, you discuss the redeveloped Ground Zero as a flawed architectural pursuit. Can you talk about the political, economic, and social factors that influenced its development?

The story of 9/11 is in part a story of architecture—after all the Twin Towers were targeted for their profile in the skyline more than for the companies within them. The demand for architectural icons and symbols in the rebuilding of Ground Zero was intensely politicized, and revealed the outsized role of real estate developers and star architects. Sadly, in a city with incredible design expertise, this has resulted in a series of banal corporate office buildings with little actual public space, and a kitschy transportation center that is really a shopping mall. In addition, all of this represents a massive transfer of billions of public funds to the private sector. The New York public deserved a lot better.

What are the memorialization trends that you see emerging in this post-9/11 period, and which trends do you see coming to an end?

The post-9/11 era can be seen as beginning with the patriotic embrace of 9/11 memorialization and ending with battles over whether to remove Confederate monuments and with the intervention of the lynching memorial into the national story. I see these forms of memory activism, whether about introducing new memories into the public arena or challenging the existing terrain of monuments and memorials, as indicative of where US cultural memory is headed. There is an increased awareness of the relationship of memory to national identity, of the importance of memorializing those who have been wrongfully killed, and of the power of cultural memory to bring key issues of the nation into the public arena.

Related Articles

Making Media Accessible to the Deaf and Hard of Hearing: an Interview with Destiny Lopez

In award-winning research, master's candidate Destiny Lopez proposes ways to make media accessible to the deaf and hard of hearing.

Media Studies Alumni Advance Field with New Scholarship

Over the past five years, graduates of the Media, Culture, and Communication doctoral program have published well received books on topics spanning the field of media studies.