A researcher at NYU Steinhardt concluded that 19th-century mathematicians used game theory to create algorithms used in today’s computation, sequencing, and logic modeling.

Want to play tic-tac-toe? You place an X in one space, your opponent places an O in another. You continue until one party has three in a row.

While the game seems simple, tic-tac-toe—along with other classic games of chance and skill—laid the foundation for the design of modern-day computers, concludes an NYU Steinhardt researcher in a newly published analysis.

“Modern computers were first imagined by mathematicians Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace in the mid-19th century, but we’re still learning more about how they did so,” says Samuel Pizelo, visiting assistant professor in the Department of Media, Culture, and Communication at Steinhardt. “The fact that games were such powerful modeling tools helps us to understand games as agents of historical change more broadly. This also gives historians and computer theorists a new vocabulary for thinking about what computation is, and what else it can do.”

Citing journal entries, publications, drawings, and correspondence by Babbage and Lovelace, Pizelo argues that they used gaming theories to model and develop complex mathematical algorithms, spatial and temporal calculations, and predictive reasoning.

These calculations were then used for Babbage’s design of the analytical engine—a steam-powered mechanical computer that inspired the first digital computers a century later. Babbage’s designs were meant to create a machine that was not only capable of storing memory and performing mathematical calculations, but also of playing games against humans by receiving information and calculating various outcomes and strategies to inform its next move.

The fact that games were such powerful modeling tools helps us to understand games as agents of historical change more broadly.

Pizelo’s article, published in Game Studies, draws connections between the duo’s work and observations, and several features of computers, including algebraic computation, probability calculations, sequencing, and if-then logic modeling.

“Have you ever seen a game, or rather puzzle, called Solitaire?...There must be a definite principle, a compound I imagine of numerical and geometrical properties on which the solution depends, and which can be put into symbolic language,” Lovelace writes in a letter to Babbage. In her letter, Lovelace refers to a version of solitaire known as “peg solitaire” played with marbles on a board.

Pizelo outlines three primary types of games and how they informed computational functioning.

Types of Games

Games of Chance

According to Pizelo, Babbage studied games of chance, such as dice games or lotteries, to develop approaches for situations where probability theory fails. Babbage observed that some games of chance that involved sequences of decisions (e.g., choosing how many times to toss a coin, or making selections of colored lottery balls from an urn) introduced new variables that are “not themselves dependent on chance.” To account for those situations, he developed formulas to explain multiple outcomes in repeated sequences.

Puzzle Games

Puzzle games like peg solitaire offered explanations of sequencing. Babbage and Lovelace both developed mathematical equations for planning out all possible marble jumps necessary for the game’s solution. Pizelo argues that these equations helped them to develop algorithms for planning successive movements of the calculating engine.

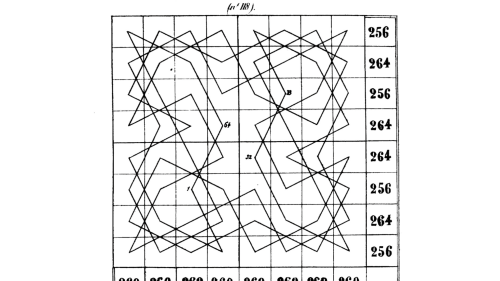

A representation of the Knight’s Tour around every square of the chessboard (Jaenisch 1862, Plate XVIII).

Games of Skill

Peg solitaire and chess offered Babbage and Lovelace opportunities to explore logic modeling. Babbage, for example, modeled every possible move that a knight could make on a chess board to inform how spaces related to one another at various time sequences. At the end of his life, he designed the first computer game for tic-tac-toe, and the first artificial intelligence program for chess.

Babbage wrote, “Is the position of the men…consistent with the rules of the game? If so, has Automaton himself already lost the game?...If not, can he win it at the next move? If so, make that move.”

“These findings are important because games are so often ignored by historians. Having clear instances where games influenced major technological innovations helps us to trace other uses for games, such as in mathematics, psychology, and artificial intelligence,” says Pizelo. The fact that dice and board games are ancient technologies that continue to influence modern technology also helps us to better understand the relationship between ancient history and our own moment. Computers are a technology the whole world helped to create.”

Press Contact

(646) 469-8496

Related Articles

African Journalists Reporting on Africa

A new book by Media, Culture, and Communication Assistant Professor j. Siguru Wahutu speaks with, and looks at the reportage of, African journalists depicting their own continent.

NEH Grant to Study Implications of AI Listening Technologies

With a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Media, Culture, and Communication Assistant Professor Edward Kang will convene experts to examine the relationship between machine listening systems and society.

How the Computer Became Personal

Media historian Laine Nooney documents the rise of the personal computer in the new book, The Apple II Age.

Related Department

Media, Culture, and Communication

239 Greene Street, 8th floor

New York, NY 10003

212-998-5191 | contact