Editor's Note: We spoke with Alexander Galloway, Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication, about the recent release of Kriegspiel and its place in Galloway's singular approach to media scholarship.

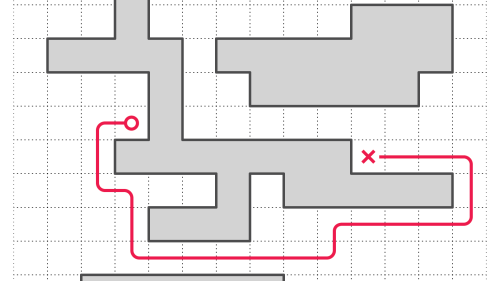

A pathfinder algorithm showing an efficient path from origin to destination that avoids obstacles.

You recently released a computer game on the App Store. That's not exactly a typical research profile for a professor in the humanities. Can you describe your approach to research, and how the game came to exist?

Research in the humanities typically involves writing articles and books. I value that aspect of the profession. But as someone who works on digital media, I also value a direct and material engagement with technology. For me this entails designing and building software. One approach I find fruitful is to unearth forgotten or otherwise obsolete software from history, and then rebuild these algorithms so they run on today's platforms. Here I use the concept of "software" very loosely; for instance a game can be reinterpreted as a form of software, even if the game was originally conceived without a computer in mind.

In this case the game comes from the 1970s. The path is a bit circuitous, if not also obscure, but in 1977 the French filmmaker and author Guy Debord released a tabletop game. I researched the game and rebuilt it to run on today's computers, along the way stumbling on some interesting mysteries (which I attempted to solve). I recount my relation to Debord's game and how it relates to computer culture more generally in the book Uncomputable: Play and Politics in the Long Digital Age.

Sometimes it's difficult to know how to make this research profile legible to others. Yet with 49,189 lines of code written over several years, followed by 9 months of beta testing, then ultimately a public release, this is the largest project I've ever worked on by far. While slightly unorthodox, hopefully it will encourage other researchers in the humanities who might also want to mix theory and practice.

You've worked on different iterations of Debord's "Kriegspiel" over a long time. Walk us through how the code has evolved into Debord AI.

The project has indeed gone through several iterations over many years. The first prototype was written in Java using a 3D game engine and a multi-player server repurposed from an MMO. It seems so bloated and over-designed in retrospect! The current version has been completely rewritten from scratch, with special attention paid to running well on mobile devices. "Debord AI" is a bit tongue-in-cheek. But I knew that I would have to model Debord's brain, or at least his play style, if I wanted the AI to work effectively. It was a difficult process, and, I admit, only moderately successful. I began using a min/max "brute force" approach, a bit like computer chess where the machine tries every possible move and then picks the best one. Although I quickly learned the shortcomings of this approach. In recent years AI has largely moved to data-driven statistical methods. Hopefully I can make a similar pivot for a future version of the game.

How does the practice of designing software inform your theoretical work?

It's a well-worn truism, but nothing can replace hands-on practical engagement with real materials. All sorts of new things appear if you pick up a device, spin it around, break it, fix it, and rebuild it. This is especially true for computers, no matter how abstract or immaterial they might seem. The book Uncomputable was organized with this in mind. I selected a series of algorithms from media history — again interpreting the term "algorithm" very broadly — and then restaged these algorithms by hand using contemporary tools. In one case it was a textile that had been originally woven using a pattern derived from algebra. In another case it was an experiment in making artificial life using short genetic codes. Or, with Guy Debord, it was a tabletop war game. In all of these case studies I tried to move simultaneously in two parallel tracks: on the one hand, engaging with more orthodox methods of historical and critical investigation (digging in archives, reading source texts, etc.); on the other hand, building working models in software, and even making some physical artifacts such as woven textiles. Working in parallel, the two tracks will necessarily inform and enrich each other.

Related Articles

In 'Uncomputable,' Alexander Galloway Offers Long History of the Digital Age

From algebraic patterns woven on a hand loom to artificial-life simulations, a new book by Media, Culture, and Communication Professor Galloway charts the history of digital media.

Alexander Galloway Named 2019 Guggenheim Fellow

Professor Alexander Galloway has been awarded a 2019 Guggenheim Fellowship.