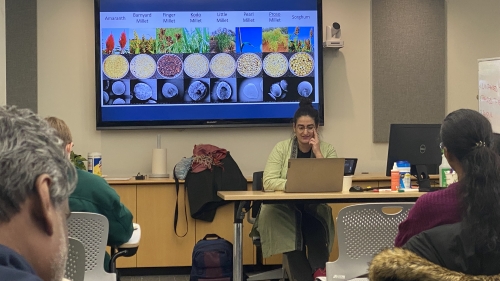

Lily Kelting, a professor of Literary and Cultural Studies at FLAME University in Pune, India, spoke about the resurgence of interest in a group of grains called millets in India and abroad. In South Asia, as elsewhere, rice and wheat have come to replace the visibility of these grains in riverine and urban diets over the last millenium. Yet many poor people living off marginal drylands have always depended on them. Their resilience in face of climate change, especially in the tropics, was underlined. This new consumer movement around grains such as sorghum, finger millet, little and kodo millet, foxtail and barnyard millet is often driven by urban residents, sometimes returnees from global professional careers. What are the connections and the contrasts between the old strength of millets and their new visibility? She addressed the new momentum -- including the declaration of 2023 as The Year of the Millet -- of these grains, including the investment of Indian government's soft power in this area. In the Q & A session, numerous interesting questions were raised about the relationship between the cultural politics of taste and personal health, and the political economy of livelihoods and infrastructural investments in poor peoples' lives.