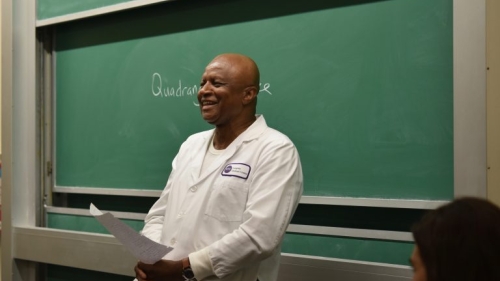

Offiong Aqua, MD, quizzes occupational therapy students on human anatomy at NYU Langone Health.

Human Anatomy, a lecture and lab course, teaches graduate occupational therapy students about the skeletal, muscular, and nervous systems through direct contact with a human cadaver.

It’s a hands-on learning experience, a “rite of passage for students,” says Offiong Aqua, MD, who holds a joint appointment as a clinical associate professor in Steinhardt’s departments of Occupational Therapy, Physical Therapy, and Communicative Sciences and Disorders.

Aqua has been teaching cadaver dissection class for 23 years; 13 years at NYU Steinhardt.

He says, “You obviously cannot study health care without understanding the structures and working of the human body. It would be like a mechanic having no clue about cars and working on them anyway.”

The class, part of the Professional Master of Science program in the occupational therapy curriculum, takes place in the basement of NYU Langone Health’s Medical School, close to the morgue. Occupational therapy students work on cadavers whose body cavities have been dissected by NYU medical students. Steinhardt students then dissect the external thoracic body, trunk, neck, back, and lower and upper extremities.

OT students during a lecture.

Aqua eases students into their dissection five months before they encounter the cadaver. During that time, they work at mastering the lecture material, a combination of intense in-class Aristotelian discussions, journal articles, and readings from Atlas of Human Anatomy. Students memorize thousands of body parts, which Aqua quizzes them on in a lecture hall adjacent to the dissection room.

He tells his students to treat the cadaver the same as they would a future patient, “with respect at all times.” He reminds them that the bodies they are about to encounter have been acquired at no cost through voluntary citizen donations.

“We are indebted to the donors and their families for giving us this opportunity to dissect and do research on human cadavers,” Aqua says.

___

On the day I visit, I watch students meet their cadavers for the very first time. They unzip a white body bag, then express varying degrees of horror and surprise when they see the body.

Then an air of clinical detachment fills the room and the students settle down and become deeply engrossed in their work. One of their assignments is to “follow the ulnar nerve to the notch where it twists around the medial epicondyle to emerge in the anterior forearm;” another is to “locate the brachial plexus.”

Finding the brachial plexus.

At each station, students collaborate with each other, pointing out the various internal organs with pincers, calling on Aqua and his teaching assistant occasionally for help.

One group’s cadaver gets special attention: a purple pacemaker is still attached to its chest wall.

The students are in a state of such deep concentration that they don’t hear Aqua tell them that class is over.

___

To some, human anatomy cadaver lab is an antiquated way of learning since plastinated bodies are state-of-the art, and 3-D software can offer a unique view of structural and topographical anatomy.

Aqua notes that the downside of anatomy software is that it is not dissectible and students cannot physically touch the computer images.

He predicts that in the future, students planning to go into surgical or health-related fields will still be using cadavers because they are unparalleled as a learning tool.

The cadaver assigned to Rachel Parroco taught her something new about the human body.

“It’s one thing to learn about the body from textbooks, visuals, and even animated videos, but to see everything in its real form and to have the privilege to touch and feel the actual body parts, is a true, authentic experience,” Parroco said.

She describes what it was like to find the brachial plexus — a network of nerves that run from the spinal cord to the armpit, supplying nerve fibers to the chest, shoulder, arm, and hand — on her cadaver.

“I used to think those nerves were very delicate and easy to tear. Feeling them at the cadaver lab, I was surprised to find out just how strong and coarse those nerves actually are,” she said.

Related Articles

Global Perspectives: OT Students Study Rehab in Israel

Associate Professors Yael Goverover and Jerry Voelbel traveled to Israel with students to participate in a course entitled “Disability in a Global Context.”

An Interview with OT Alum and Blogger Sarah Lyon

Lyon is the founder of the well-known OT blog, "Potential." Read on to learn about Sarah's experience at NYU Steinhardt and what inspired her to become a blogger.

OT Students Study Autism in London

We spoke with Francine Cacciola (MS '19) about her experience studying abroad in the United Kingdom.