Lara Saguisag, Steinhardt's Georgiou Chair of Children's Literature and Literacy, shares her vision for Steinhardt's Constantine Georgiou Library and Resource Center for Children and Literature.

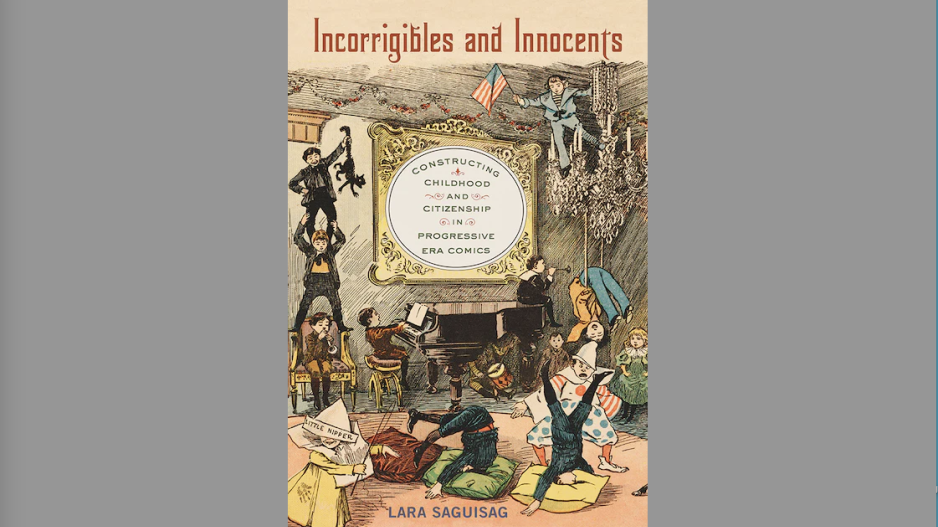

Lara Saguisag, holds NYU Steinhardt's Georgiou Chair in Children's Literature. She is the author of a monograph, Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics (Rutgers UP, 2018), and the author of several children’s books, including Animal Games (Anvil, 2016) and the award-winning Children of Two Seasons: Poems for Young People (Anvil 2007).

We spoke to her about her research, scholarships, and plans for Steinhardt's Constantine Georgiou Library.

Can you tell us about your current project on climate justice and children's literature?

A few years ago, I started experiencing intense climate grief. News of extreme weather events would just leave me despondent. I would start thinking, “What’s the use of my research and writing when the world is burning? How come people don’t seem to care about these heat waves and firestorms and superstorms?” To deal with my anguish and paralysis, I started getting involved with a local climate justice group and reading essays by climate activists. I realized then that a lot of people—including children and teens—do care. I also recognized that I can use my knowledges and academic training to contribute to the fight for a better world, a world where we care for one another and our planet.

My current project is hopefully one such contribution. I’m working on a book manuscript that is tentatively titled When Oil and Childhood Mix. It examines the ways fossil fuel industries are represented in children’s books. I’m still in the early stages of my research, but I’ve come across a number of picture books, nonfiction titles, and comics that depict coal, fracked gas, and oil as essential fuels that power the United States, that guarantee American exceptionalism. But there are also books that try to imagine a world beyond fossil fuels and encourage young people to recognize the terrible consequences of our continued dependence on coal, methane, and petroleum.

I also think a lot about how we can develop what I would call “climate justice pedagogies.” How can climate justice movements inform our teaching practices? I’m interested in how, in teaching about climate change, we can integrate literature and the arts and encouraging climate activism. I’m also looking at ways we can reorient teaching away from ideologies of extraction and accumulation and toward values such as renewal, reciprocity, repair, and community. I don’t think we have to reinvent the wheel here. We can turn to already existing critical pedagogy frameworks and models of equitable and accessible teaching to foster learning even in the face of increasingly more frequent climate disasters and to resist neoliberal education that treats people and nature as resources to be exploited.

I’m interested in how, in teaching about climate change, we can integrate literature and the arts and encouraging climate activism."

You are the author of Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics. Why do you think that comics are so appealing now to readers?

I think comics have always been appealing! My sense is that young people are drawn to comics because of their “forbidden” status, and because comics often provide the action, humor, and energy that readers might feel are missing from so-called traditional literature. There is no doubt that comics have become more mainstream in the twenty-first century. Dav Pilkey’s and Raina Telgemeier’s books are runaway bestsellers and their creations have become cultural phenomena. I still do hear people asking if reading comics counts as real reading. There is a lingering distrust of the medium, or a persistent view that comics are legitimate only because they are stepping-stones to “real” books. Many parents happily give their children copies of Dog Manand Captain Underpants, but I suspect they some of them think these are “silly books” that their children will eventually outgrow. But when you examine Pilkey’s series, you’ll see how incredibly radical and challenging they are. He encourages young people to create their own comics, to recognize and reject adult hypocrisy, to realize how schools focus more on standardized testing than fostering creative and critical thinking.

In Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics (Rutgers University Press, 2018), Lara Saguisag, associate professor and Georgiou Chair, shows how child characters in comic strips expressed and complicated contemporary notions of who had a right to claim membership in a modernizing, expanding nation.

In comics, as in other forms of popular culture, racist, sexist, homophobic, and transphobic images often bubble up and circulate. The medium typically utilizes caricature, and so often we encounter characters that are simplified, flattened, and reduced. But comics is also a space where we can question such images and turn them on their heads. Comics requires active participation from the reader—we fill in the gaps between the panels, we try to make sense of the relationships between the words and images. So, as active readers, comics readers, young and old, have the capacity to refuse and question harmful characterizations. We don’t have to be passive receptacles that just uncritically imbibe reductive images—we can engage with them by questioning them, rejecting them, and providing alternatives.

Many authors are turning to comics because they understand it to be a medium that appeals to young people, and they thus use comics to give voice to communities that have been silenced and to introduce readers to histories that have been erased. For example, Brian K. Mitchell worked with Barrington S. Edwards and Nick Weldon to produce Monumental (2021), a graphic novel that tells the astonishing story of Oscar Dunn, the first Black American to serve as lieutenant governor and acting governor. Frank Abe collaborated with Tamiko Nimura, Ross Ishikawa, and Matt Sasaki to produce We Hereby Refuse, a powerful graphic novel about Japanese incarceration during World War II. These titles remind us that comics have long been used to educate readers and raise political consciousness.

A student teacher shares a science book and experiment with young readers at the Georgiou Library.

As a literary scholar, researcher, and poet, what will you bring to your position as Georgiou Chair?

One of my aims as Georgiou Chair is to honor the global diversity of children’s literature, and specifically bring more attention to books produced in the Global South. Institutions in wealthier nations often have the resources to collect, study, and promote their literature for young people.

I grew up in the Philippines and most of the books that I read as a child were published in the US and the UK. When I thought of building a career in children’s literature studies, I decided to go to graduate school in the US because I felt I had to study in a country that had a rich history of children’s literature. It was being away from my home country that made me recognize and appreciate the complex and dynamic history of Filipino children’s literature. I had to confront the colonial mentality that made me assume that books published in the Philippines are inferior to those produced in the US and the UK.

Literatures produced in economically poor nations are often neglected in histories and criticism. I’m hoping that my work at NYU can support scholars, authors, and illustrators from the Global South; highlight the diversity of children’s stories and lived experiences around the world; and ultimately facilitate expansion of our definitions of children’s literature.

I am excited to work closely with Kendra Tyson and discuss what we can do to expand and diversify the Georgiou Library collection, find more space so young visitors can enjoy the library, and offer robust programming throughout the school year. I’m really hoping that we can turn the Georgiou Library into a hub for scholars in the New York metropolitan area—I would love for it to become a space where folks interested in studying issues of justice in children’s literature can meet, co-create, and build relationships.

I also want to make sure that the Georgiou Library can showcase the intersections of academic research, activism, and community engagement. Through partnerships with other New York City institutions, by cultivating long-term relationships with members of Black, Brown, immigrant, working-class, and poor communities across the five boroughs, the Georgiou Library can generate and sustain programming that promotes reading as well as provides children and teens the space and means to write, collaborate, share, and distribute their own stories. I’m hoping it can be place where we can share and create and respect stories that come in different forms and are told from different perspectives.

I