Benjamin Westphalen

Congratulations to Benjamin Westphalen, masters student in the Program in Screen Scoring, for composing the score for A Dream Called Khushi (Happiness), which won the 2024 Student Academy Award Bronze in Best Documentary category. The documentary tells the story of a young Rohingya refugee, Khushi, and her desire to receive an education while enduring the harsh reality of life in a Bangladesh refugee camp. Her encounter with Rishabh Jain, an AP journalist, becomes a turning point, as his reporting on her struggles ignites public outrage and highlights the plight of the Rohingya, a community deprived of basic rights. Benjamin discussed his experience in scoring the documentary.

What was the most challenging part of composing for this documentary considering its sensitive and complex subject matter?

The most challenging part was probably that it's such a big issue, and the story is about one person. One of the things I was always thinking about when writing the score was that I needed to write sad, but also hopeful music. I mean, it’s a hopeful story, but at the same time, it only scratches the surface of a much bigger problem. I had to make the music sound not too big, but still give it a sense of potential. So you feel it’s a big thing that’s happening.

Another challenge was having the music, in some way, represent the location. But as I’m not remotely from there and not a composer of Rohingya music or, in any way, Southeast Asian music, I had to find a way to do that without sounding fake.

How did you approach capturing the emotions and experiences of the young girl, Khushi?

I tried to capture what Khushi went through by presenting emotions that maybe don’t fully come through on screen. I mean, there’s a saying in film music: “Tell the story that isn’t told,” or that is hard to see on screen. That means sometimes it’s important to leave out music if it’s very clear what’s on the screen. You don’t want to interfere with what’s being said or shown. There were some scenes where I thought, “Should I even add more to this?” and decided not to. I was in contact with my director—who is a great guy—and we were on the same page the entire time.

Were there any particular instruments you used to represent the refugee camp or Khushi's desire for an education?

That kind of relates to the first question—how to represent this story as a whole. I always went for something more intimate with a subtle but bigger-appearing background. For example, I mostly used a simple nylon guitar for anything related to Khushi and her journey to get an education.

Otherwise, I incorporated some percussion sounds whenever something was moving in a particular direction. Doing something more rhythmic felt natural—it’s quite common in film music. Also, whenever the documentary shifted, whether in tone or setting, I tried to incorporate original Rohingya music and, at some point, mixed it with film music. For example, when Khushi makes it to Canada, there’s a scene where they leave Bangladesh. You hear Rohingya music at first, but as they fly out, that music gradually fades into a more spacious, synthesizer-based score—though still organic-sounding.

How has your time in the Screen Scoring Program shaped your approach, decision making and confidence?

The Screen Scoring Program and the experiences I have had in it definitely shape my approach to scoring and decision-making. You’re constantly seeing how talented your classmates are, which can be intimidating at first, but it also makes you feel like you’re part of an incredible group. That’s something filmmakers notice too.

Being part of such a skilled group of composers leads to filmmakers placing a lot of trust in us. That respect is really motivating. When you’re trusted, it naturally makes you more confident, and that confidence allows you to make decisions without overthinking too much. Of course, if you do find yourself overthinking, it’s usually because something isn’t quite working, and it’s worth addressing.

Another factor is the restricted amount of time. That forces you to make decisions quickly and not hesitate too much. You’re writing music all the time—before the program, but especially during it, you’re composing daily—and that constant practice helps you trust your instincts. You don’t worry so much about whether something is perfect; you just keep moving forward.

Are there collaborative opportunities in the Screen Scoring Program that mirrored the experience of working on this documentary?

Yes, they’ve all been different in terms of how you work with the director and approach the film. Every film is unique—unless, of course, you’re working with the same director. I worked on a documentary with my friend and classmate, Josh Conway, who is also in the Screen Scoring program. That collaboration was fantastic because it reinforced something I’ve realized over time: the more you delve into film music and how to work as a composer, the more you appreciate sticking to your strengths.

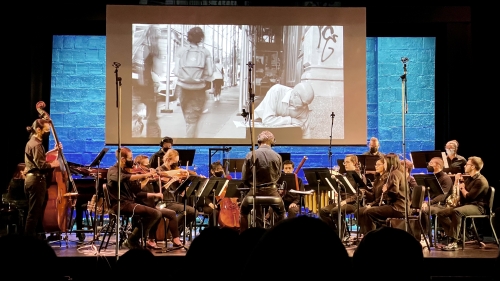

My background is a bit unusual—it’s rooted in hip-hop production, electronic music, and, of course, the style I used in A Dream Called Khushi. When I collaborated with Josh, who’s an incredible orchestral composer, we decided to merge our strengths. The documentary we worked on was about street art in London and its history, so we created a score blending orchestral music with drill beats. Josh wrote the orchestral parts, and I sampled them into hip-hop and drill beats. The director loved the concept, and it turned out really well.

I’ve worked on other collaborations, like a dance film by a Tisch drama student. That was a completely different experience. It was only about three and a half minutes long, but because it was choreographed, it essentially became a music video. Music played a huge role in shaping the choreography, so it felt very impactful.

Right now I’m working on a documentary about an Indigenous community in Mexico. It’s still in the early stages, but I feel like my previous experiences, especially with documentaries, have prepared me to approach this project thoughtfully. While every film is different, I’ve learned to identify what’s important for the format I’m working on and how to adapt to it.

A big part of these collaborations is getting along with the director. If you click with them, it’s ideal because, ultimately, the dynamic matters as much as the music. You need to be able to spend hours together under stressful conditions—whether in an editing booth or a mixing room—and still get along by the end of it.

One thing I’ve noticed in the Screen Scoring Program is how talented everyone is. It’s not like anyone can walk in and claim, “I’m the best composer in my cohort.” Everyone has their own strengths, and that’s what makes it exciting. The goal isn’t to compete; it’s about finding the right fit for each project. So, yes, collaborations are as much about understanding the director’s vision as they are about working well together. It’s crucial to build a relationship where you respect each other’s input and feel comfortable working together long-term without personality clashes.