James Weldon Johnson with Fisk University students and faculty in 1932. Two years later, he accepted the role of visiting professor of creative writing at NYU. (All photos appear courtesy of the Carl Van Vechten Papers Relating to African American Arts and Letters, James Weldon Johnson Collection, in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; the Carl Van Vechten Trust; and the James Weldon Johnson Foundation.)

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place For which our fathers died.

When Grammy-winner Andra Day performed “Lift Every Voice and Sing” at the Super Bowl earlier this month, a worldwide audience of 123 million people listened to its message of African American struggle and resilience. Evoking the Biblical exodus from slavery, the song was a frequent soundtrack of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s and is often called the Black National Anthem.

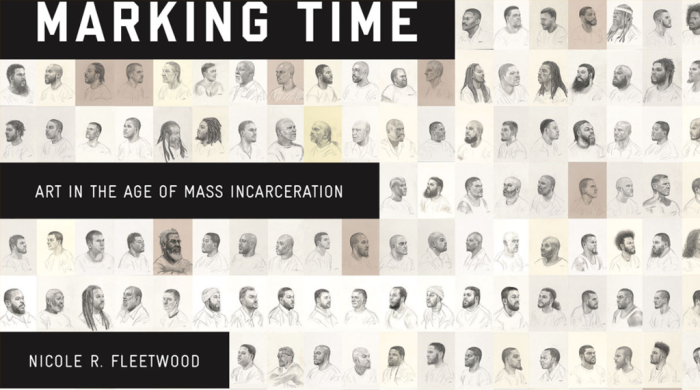

NYUers watching that performance may not have been aware of its connection to a major milestone in the University’s history: the lyrics of the song were written in 1900 by James Weldon Johnson, who would 34 years later become the University’s first Black faculty member. Today, the University honors his legacy of intellectual curiosity and social impact with the James Weldon Johnson Professorship, which offers research support to NYU faculty. These scholars represent disciplines such as law, education, global public health, and the arts, and are engaged in projects including the NYU Migration Network, the Attachment and Health Disparities Research Lab, and Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration.

As one of the leaders of the Harlem Renaissance, Johnson was, himself, a true Renaissance man. A civil rights activist, poet, lawyer, politician, writer, and educator, he was born in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1871, just eight years after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. He attended the Stanton School, the state’s first all-Black elementary school (where he would later become principal), and eventually graduated from what is now Clark Atlanta University, the first HBCU established in the South. He then studied law, and in 1898 became the first African American admitted by examination to the Florida Bar.

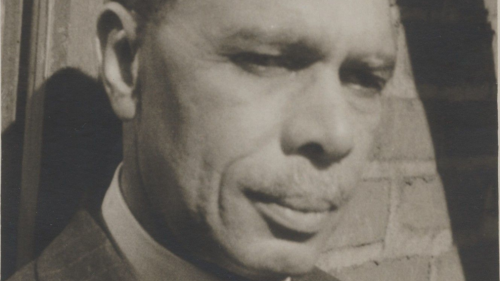

James Weldon Johnson in 1932

In 1901, a shared love for writing poetry, prose, and music drew him and his brother, John Rosamond Johnson, to New York City, where they immersed themselves in the theater scene, eventually writing and composing over 200 Broadway and Vaudeville tunes. They were inspired in part by their initial success with “Lift Every Voice,” written originally as a poem by James and then set to music by his brother to be sung by Stanton School students for a performance commemorating Abraham Lincoln’s birthday.

Life in New York captivated Johnson, and he used his array of skills and talents to forge connections within diverse communities. In 1904, he worked on Theodore Roosevelt’s successful presidential campaign, prompting Roosevelt in 1906 to appoint Johnson as US Consul to Venezuela, and then to Nicaragua three years later. After seven years of service overseas, he returned to the City in 1913.

Johnson's Harlem home at 187 W. 134th Street

In 1915, Johnson joined the staff of the NAACP, where he rose to eventually become its executive secretary. In the coming years, as racial tensions escalated throughout the US, he worked with contemporaries like W.E.B. Du Bois to speak out against lynchings and violence. He organized the NAACP’s Silent Protest Parade on Fifth Avenue in 1917, which was one of the first mass demonstrations by African Americans. The NAACP adopted “Lift Every Voice and Sing” as its official song in 1919.

Johnson did some of his most acclaimed writing in the 1920s and 30s, publishing The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927), and a 1927 reprint of his 1912 novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, which he originally published anonymously because he was concerned that the topic of racial discrimination might hurt his diplomatic career. In 1926, he and his wife, Grace Nail, bought a country home in the Berkshire Mountains of Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

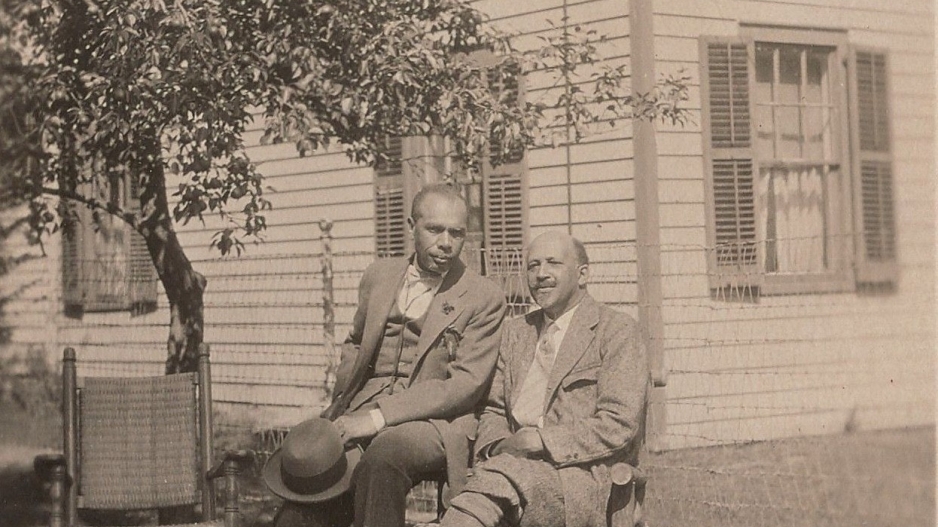

Johnson, left, with W.E.B. Du Bois in 1928 at his Five Acres home in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

Called Five Acres, the house became a haven for respite and creativity, and also a rare place for the Johnsons to feel a sense of belonging among fellow activists and artists. Johnson penned his autobiography, Along This Way (1933), in a small writing cabin in the nearby woods. Today the home is owned by Rufus Jones and Jill Rosenberg Jones, executor of Johnson’s literary estate. Together they run the James Weldon Johnson Foundation, which is devoted to advancing his legacy through artist residencies, student programs, and restoration of his writing cabin.

Johnson helped organize the NAACP’s Silent Protest Parade, which was one of the first mass demonstrations by African Americans.

After retiring as head of the NAACP at age 59, Johnson returned to education in 1930 as a creative writing teacher at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee.

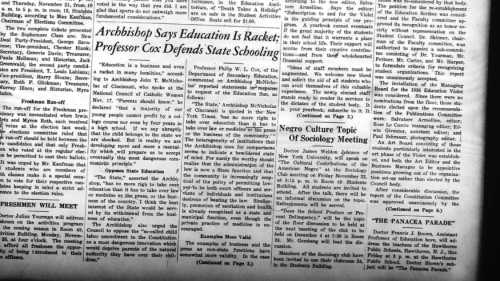

In 1934, he accepted another teaching appointment as Visiting Professor of Creative Writing at the NYU School of Education (now NYU Steinhardt), becoming the University’s first Black professor. Student newspaper accounts from this time note that Johnson spoke on “The Cultural Contributions of the American Negro” at a lecture hosted by the NYU Sociology Club, and that he hosted in his classes a number of acclaimed musicians of the day, including his brother as well as W.C. Handy, composer of the song “St. Louis Blues.”

A student paper from 1934 advertised one of Johnson's lectures to the greater NYU community. (NYU Archives)

Johnson died tragically at age 67 on June 26, 1938, when his car was hit by a train while he and Grace were vacationing in Maine. More than 2,000 people attended his funeral, which was held in Harlem. A eulogy delivered by Gene Buck, President of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers, noted that Johnson “found new frontiers of the heart and mind... He had nobility, culture, infinite taste and a burning desire for learning and tolerance that would not cease.”

All photos appear courtesy of the Carl Van Vechten Papers Relating to African American Arts and Letters, James Weldon Johnson Collection, in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; the Carl Van Vechten Trust; and the James Weldon Johnson Foundation.

Related Articles

More Acclaim for Professor Nicole Fleetwood's 'Marking Time'

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Harvard University Press, 2020) garners additional recognition with two prominent scholarly awards.

Global Media Research with Impact

Media, Culture, and Communication's Paula Chakravartty has been appointed a James Weldon Johnson Professor by the Provost's Office in recognition of her research on racial capitalism and global media infrastructures, as well as migrant labor mobility and justice.

Nicole Fleetwood Receives $1M Grant from the Mellon Foundation for Prison Art Initiative

Support of Steinhardt Professor Nicole Fleetwood's Marking Time initiative will amplify the art of the incarcerated.