By Norm Fruchter

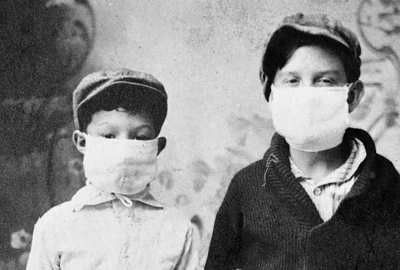

In 1918 the Spanish Flu, an epidemic caused by the H1N1 influenza virus, swiftly became a pandemic that ultimately infected some 500 million people worldwide, almost 30% of the global population. Across the U.S., the Spanish Flu killed an estimated 675,000 people out of a U.S. population of 105 million, a .6% deaths-to-population rate. In New York City, the pandemic caused more than 33,000 deaths in a population of 5.6 million, a deaths-to-population rate that very closely mirrored the nation’s. This unexpectedly low rate belied the reigning assumption that New York City’s density and poor living conditions would intensify the flu’s infection rate and increase its virulence.

Given New York City’s very high infection and death rates in the initial stages of the current COVID-19 pandemic, what can be learned from how the city responded to the 1918 Spanish Flu? A 2010 paper, “Better Off in School”: School Medical Inspection as a Public Health Strategy During the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic in the United States, by Alexandra Minna Stern, Mary Beth Reilly, Martin S. Cetron, and Howard Markel, provides a fulsome account of how New York City and its school system dealt with the Spanish Flu. There are some obvious comparisons. In 1918 New York City’s leaders chose to keep the school system open, while most U.S. cities closed their schools. To combat the COVID 2019 pandemic, state and city leadership closed schools and essentially shut down the city. As of Fall 2020, most U.S. urban school districts have gone virtual to mitigate the pandemic, while NYC is struggling to make a hybrid system work. Another major difference is that in 1918, many of the city school system’s buildings, and its public health and school health efforts, were designed to meet the challenges of a major pandemic. The following account summarizes Stern and her colleagues’ description and analysis of public health and public schooling as New York City confronted the Spanish Flu.

In the fall of 1918, U.S. schools were experiencing dramatic physical, social, and pedagogical challenges. Public school enrollment had increased considerably since the late 19th century, particularly in urban areas, which by 1920 accounted for more than 50% of the U.S. population. But conditions in city schools, many of them serving a burgeoning immigrant population, were often squalid and unhealthy – buildings weren’t fireproof, there was rarely electricity or indoor plumbing, and classes were often held in poorly lit, poorly-ventilated space. Consequently, improving public school facilities and upgrading schools’ poor sanitary conditions became a central focus of Progressive-era reformers.

In 1898 a New York City reform administration appointed Charles B.J. Snyder as the school system’s Chief Architect. Snyder believed school buildings should function as civic platforms for a better society and worked to improve fire protection, ventilation, sanitation, lighting, and flexible space in the city’s schools. He incorporated new engineering concepts and new materials to design schools with walls of large windows to provide ample light and ventilation. The new materials he used also reduced flammability and allowed for lighter but sturdier floor loads. Snyder’s hallway designs improved traffic and air circulation, and he incorporated auditoriums, gyms, pools, and rooftop playgrounds into his new buildings. His H-plan design provided two wings with side courts to bring floods of light and fresh air into classrooms. The H-plan schools also featured grand courtyard entrances and provided spacious and protected recreational areas between the wings. From 1898 till his retirement in 1923, Snyder designed more than 400 schools; most are still in use throughout the city. “Where he found barracks,” Jacob Riis, the author of How the Other Half Lives, wrote of Snyder, “he is leaving palaces to the people.” (Thanks to Jean Arrington for her photos and her dedicated research on Snyder’s buildings.)

The Progressive reformers also implemented school health programs to develop a healthy and intelligent citizenry, along with public health programs to reduce the ravages of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, especially in immigrant communities. Before the Progressive era, vulnerable children with contagious diseases were barred from schooling and, consequently, from prompt medical attention and treatment. To remedy this, in 1893, New York City appointed the nation's first medical inspector and established a school health inspectors’ corps. The nation’s first school nurse program began in New York City in 1902 and was quickly expanded to all the city’s public schools. Nurses examined students’ eyes, hands, throats, and hair, treated individual students’ health needs, and visited homes to provide information about communicable diseases. When the Spanish Flu arrived in NYC in late September 1918, the city had built a comprehensive school health infrastructure to mobilize against it.

Dr. Royal S. Copeland, the city’s Health Commissioner, initially opted for quarantine and isolation to mitigate the pandemic, and contemplated closing schools with infected students and imposing system-wide closure if necessary. Most U.S. cities had closed their public schools as the Spanish Flu spread. But Dr. Josephine Baker, director of the city’s Department of Health Bureau of Child Hygiene and a leading Progressive-era reformer, persuaded Copeland to keep the city’s schools open. Baker argued that the city’s school health system would keep students safer in their classrooms than in their homes and neighborhoods.

In 1918 the city’s school system served nearly a million students, the great majority crowded into tenements whose conditions made their dwellers vulnerable to infectious diseases. For students from tenement districts, Baker argued, schools offered a clean, well-ventilated environment where teachers, nurses, and doctors could monitor, identify, and combat the Spanish flu. Teachers could look for signs of upper respiratory conditions, and students with symptoms could be sent to an isolation room for a medical examination. If they needed to be quarantined at home, Health Department personnel could accompany them and assess whether home conditions could support effective isolation and care. When homes seemed inadequate, children could be sent to a hospital. Copeland ultimately decided to keep schools open, agreeing with Baker that the city’s students would be better protected in their schools.

In their study, Stern and her colleagues conclude that New York City limited the toll of the Spanish Flu for several reasons. First, citywide forces implementing mitigation strategies were effectively coordinated by a citywide advisory committee, a women’s volunteer committee, and a nursing committee. Second, the city’s leadership mobilized its public health resources, its comprehensive school health system, and implemented the lessons learned from responses to earlier outbreaks of polio, diphtheria, and cholera in the struggle against the Spanish flu. Finally, Copeland consistently displayed effective leadership and his public persona projected a sense of calm, reasonable assurance.

As we enter the eighth month of the current COVID-19 pandemic, consider some clear contrasts to the city’s efforts in 1918. Current city leadership has not effectively mobilized the city’s volunteer capacities, though thousands of non-profit service agencies and grass-roots groups are independently working to staunch the gaping holes in the city’s threadbare and inequitable safety net. Both city and state political leaders have often been irresolute, indecisive, and fractious. The city school system, for example, was not closed quickly enough. Worse, the six-month planning period between the closing and reopening of schools was squandered, resulting in reopening plans that were so inadequate they necessitated at least two postponements.

But the sharpest contrast between the present and 1918 is the erosion of the city’s schooling and health systems that fought the Spanish flu. From 1900 to 1950, New York City built five times the number of schools than were constructed in the seventy subsequent years (1950 to 2020). And as the city’s schooling population shifted from majority white to majority students of color in the years following 1950, recurrent fiscal crises, savage budget cuts, and systemic neglect imposed by city and state leadership severely weakened the capacity and effectiveness of the city’s school system.

Similarly, from 1900 to 1950, the city developed the nation’s largest public hospital system and a school health service renowned for protecting its vulnerable students. After 1950, as the city’s white population began to move to the suburbs and was replaced by growing numbers of Black, Latinx, and Asian families, city and state leadership consistently underfunded the city’s public health services. The hospitals, clinics, and community health centers that predominantly served those newer populations were denied the critical resources they needed, and many were shuttered. As a consequence, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck New York City early in 2020, two of the city’s basic infrastructures, public schooling, and public health, had been so systemically weakened that they were often overwhelmed in the struggle to protect and sustain our city’s most vulnerable populations. Atul Gawanda, in a column about the COVID-19 pandemic in the October 5th issue of The New Yorker, ends his piece with a similar warning: “Repairing our systems of medical care and public health isn’t an elective procedure. The afflictions of our body politic threaten the well-being of us all.”