Seth Badu & Shana DeVlieger

In a world where the promise of education as the great equalizer remains unfulfilled, the pursuit of equity in early childhood education is more urgent than ever. Persistent opportunity gaps and disparities in outcomes for young children from marginalized communities highlight the ongoing work ahead. As a society, we cannot afford to ignore the critical role early childhood education plays in shaping young learners' futures and laying the foundation for a more just and inclusive world. Equity in early childhood education is not just a principle; it is a moral imperative.

Imagine: A world where every child, regardless of their background, enters a classroom that celebrates their unique cultural identities, diverse knowledge, and rich lived experiences. In this world, the cultural wealth (Yosso, 2005) they bring—the values, traditions, and knowledge passed down through generations—is recognized as an invaluable asset, enriching the learning environment. Each child’s story is a source of pride and wisdom, shaping the curriculum and informing teaching practices to honor the diversity of the world around them. Can you see it?

This is the world that our research team envisions. We are motivated by the unwavering belief that this vision is not just idealistic; it is achievable and essential. At the same time, we recognize the significant, longstanding deficit perspectives faced by historically marginalized caregivers and children, particularly those that are racially, culturally, linguistically, and socioeconomically diverse. Therefore, we advocate for disavowing terminology that diminishes their humanity and contributions, which is crucial for anti-racist and anti-bias transformations in early childhood education.

In this spirit, we recently investigated how the latest iterations of the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) texts, foundational guidelines for early childhood communities, have evolved (or not) to promote more inclusive, reciprocal partnerships between families and educators. We considered specific features of the editions published in 2009 and 2020/2022 by tracing changes in the language and framing of family-educator relationships and finding evidence of a commitment to shared power and collaboration. We found that the discursive changes in the DAP texts represent a comprehensive rethinking of what knowledge and whose culture “counts” in early childhood education contexts. This shift reflects a broader recognition that all children and their families possess valuable cultural resources and knowledge that should be actively integrated into early learning environments. This is encouraging. And, we argue for continued discursive shifts to bring us closer to actualizing the vision of justice.

NAEYC and DAP

NAEYC was founded in the 1920s by educators and professional researchers who initiated the organization of nursery schools for young children (NAEYC). Concerned about the quality of the proliferation of nursery school programs, Patty Smith Hill convened a multidisciplinary group of 25 individuals to discuss the need for a new organization. A public conference was held in Washington, DC in 1926. By 1929, the association had taken on the name National Association for Nursery Education (NANE). The organization was renamed the NAEYC in 1964, following a substantial surge in membership during the 1950s (NAEYC).

Grounded both in the research on child development and learning and in the knowledge base regarding educational effectiveness, NAEYC published a position statement in 1986 titled “Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs” (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009). The following year, it was expanded into a book that defines what is ‘appropriate and ideal’ for promoting children’s learning and development (Wright, Friedman & Bredekamp, 2024). Since then, they have come to serve as well-regarded benchmarks for implementing high-quality early learning and care pedagogies and practices in settings serving children from birth through age eight in the United States and abroad. Editions of the position statement and book have been published approximately every 10 years since then [1986/1987-1996/1997-2009 and 2020/2022 (Wright, Friedman & Bredekamp, 2024)]. Each publication has evolved slightly to reflect the zeitgeist and politics of the time.

In our present era marked by the defunding of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives and book bans across the United States, the role of organizations like NAEYC becomes increasingly complex. As a national organization with chapters in states such as Alabama (where educators and administrators often fear repercussions for being perceived as too progressive or "woke"), NAEYC must navigate divisive issues carefully. As researchers, we have the benefit of applying critical theory to interrogate policies’ underlying assumptions and implications. Our work falls within the critical tradition, scrutinizing social systems and structures, particularly focusing on power hierarchies, social injustices, and the unexamined presumptions of dominant ideologies such as settler colonialism, patriarchy, white supremacy, capitalism, and imperialism (Doucet 2019a). Key theoretical influences include Critical Race Theory (Delgado and Stefancic 2001), Black and intersectional feminist theories (Collins 2000; Combahee River Collective 1982; Crenshaw 1989a, 1989b; hooks 1981), and anticolonial theorists like Fanon (1961), Saïd (1979), and Spivak (2010).

We applied these critical perspectives to our analysis of the DAP texts, aiming to show how language shapes policy and practice, and how both can be reshaped to foster anti-racist partnerships. Specifically, we asked:

- What is the form and function of the language in the 2009 and 2020/2022 versions of the DAP texts?

- What discursive shifts have occurred between these versions?

- What might the discursive shifts between editions tell us about NAEYC’s stance vis-a-vis equity and anti-racism?

Our understanding of language is informed by Wodak’s critical linguistics (1989), Gee’s discourse theory (2008), and critical discourse analysis (CDA) (Fairclough 2015). Wodak examines how language mediates power and ideology, and in education, critical linguists reveal how political power relations shape school language.

Discourse involves the exchange of ideas through language, and Gee (2008) distinguishes between ‘little d’ discourse (specific language use) and ‘big D’ Discourse (broader ways of being). Critical discourse analysis (CDA) focuses on power relations and inequalities in producing social wrongs, aiming to identify causes and contribute to solutions (Fairclough 2015). In this study, we were specifically interested in understanding how the DAP texts might "operate in particular political interests to sustain relations of domination and power" (Luke 1995, 18). Quantitatively, we used text analysis software, including LIWC-22 and KH Coder, to support our qualitative findings. We analyzed word frequencies, co-occurrences, and designed custom dictionaries to capture our specific research interests.

Discursive Shifts and Implications for Equity

We found that there is a substantial linguistic shift between the two versions of the texts that we analyzed. For example, in the 2009 edition, "practitioners" and "teachers" were used to describe people who work with young children. In the 2020/2022, "educators" was used instead, acknowledging their broader roles and responsibilities. Also, the language transitioned from passive constructions to explicitly identifying educators as responsible agents who initiate engagement, welcome participation, and adapt communication strategies. The framing of family-educator relationships also evolved to emphasize more inclusive and reciprocal partnerships, honoring families' goals, perspectives, as well as capacities for decision-making.

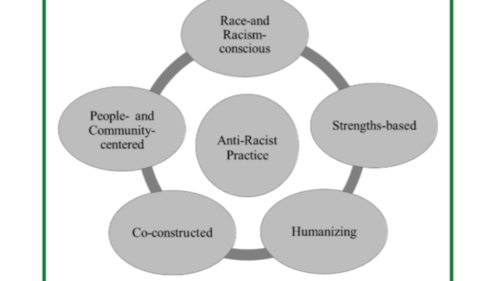

We also found that the 2020/2022 texts place greater emphasis on cultural inclusivity and anti-bias strategies, acknowledging the importance of understanding the unique context of each child and the valuable knowledge held by families. Nevertheless, our analysis through the lens of Doucet’s anti-racist framework revealed that, while the texts pay attention to some aspects of the framework, such as being strengths-based, co-constructed, humanizing, and people- and community-centered, there is a lack of explicit attention to race and racism. Even though we find the changes to be a big step forward, we believe that NAEYC needs to make a stronger and direct call for anti-racist practices in family-school partnership. By openly discussing race, racism, and power relations, NAEYC may help promote equity and social justice in early childhood education.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Policymakers should consider revising existing guidelines and standards to better reflect the importance of culturally responsive practices and reciprocal partnerships with families and communities. We call for incorporation of explicit language about anti-racism, equity, and social justice into policy documents and providing resources to support the implementation of these principles in practice.

At the classroom level, we recommend that educators should begin to critically examine their own biases and assumptions about children and families from diverse backgrounds. They should strive to create inclusive learning environments that value and build upon the unique strengths, knowledge, and experiences of all children and their families. This involves adopting culturally responsive teaching strategies, such as incorporating children's home languages and cultural traditions into the curriculum, and engaging in ongoing, two-way communication with families to foster mutual understanding and respect.

We recognize that implementing these changes may present challenges, such as resistance from stakeholders who are accustomed to traditional, school-centric approaches to family engagement. Educators will also need additional training and support to develop the skills and knowledge necessary to effectively engage in reciprocal partnerships with diverse families and communities. Despite these challenges, embracing culturally responsive practices and authentic partnerships presents valuable opportunities to promote equity, social justice, and improved outcomes for all children.

Suggestions for Future Research

Future research could look at how these guidelines and the broader DAP framework are adopted, interpreted, and implemented in low-and-middle income country contexts outside of the United States. As mentioned, previous studies have pointed out tensions between DAP principles grounded largely in practices of WEIRD communities (Castner 2021; Hsieh 2004). Hence, there may be even greater mismatches in countries classified as low - or middle-income, where lack of resources, high teacher-student ratios, emphasis on academic achievement, and cultural variability pose barriers to strictly implementing the DAP framework. It would be important to investigate how educators and policymakers in specific low- and middle-income countries make sense of and reconcile external guidelines like NAEYC’s DAP framework. Two questions to address include.

- What aspects of DAP align with or contradict local norms around areas like learning through play, child-centered pedagogy, and family-school partnerships?

- How do educators in these settings negotiate external pressures and recommendations with community needs and perspectives?

Studying the localisation process as DAP principles spread globally can further enrich critical perspectives and help ensure greater cultural responsiveness.

Conclusion

We envision a world where every child's cultural identity and lived experiences are celebrated and integrated into their learning journey from the outset. By addressing deficit stereotypes and fostering anti-racist and anti-bias transformations, we move closer to ensuring that every child has access to high-quality early education, laying the foundation for a more equitable future. Our recent paper illustrates how the language we use can play an important role in shaping guidelines for these efforts that promote inclusivity and reciprocal partnerships. While some efforts have been made to reflect a broader recognition of the valuable cultural resources that all children and their families bring to early learning environments, much work remains to be done. We look forward to advancing this work in our upcoming research on exploring how Ghanaian early childhood education stakeholders (e.g., teachers and early childhood coordinators) can bridge cultural diversity and NAEYC’s DAP guideline ‘2’ to enhance school-family partnerships. We seek to identify barriers to effective school-family partnerships and develop strategies that honor the cultural wealth present in Ghanaian communities.

Seth Badu, MPhil, is a PhD student in Early Chldhood Education in the NYU Steinhardt Department of Teaching & Learning.

Shana DeVlieger, MAT, Ed.M, is a PhD candidate in Urban & Early Childhood Education in the NYU Steinhardt Department of Teaching & Learning.