By Norm Fruchter

In late November in the Fordham Institute’s Flypaper, Chester Finn disparaged New York City’s Community School District 15’s effort to reduce segregation and improve integration across the district’s eleven middle schools. (The NYC school system, serving 1.1 million students, is divided into 32 administrative districts.) Finn framed District 15’s reform as “social engineering,” downplayed the almost uniformly positive gains in student diversity at the middle school level in the reform’s initial year, and focused on a struggling middle school that showed very limited enrollment gains for the reform’s targeted priority groups (see below).

Using social engineering as a disparaging label for government-driven planning has been a staple of conservative criticism for decades. The notion stems from the work of F. A. Hayek, an Austrian-British economist and philosopher whose theories inspired the Thatcher and Reagan regimes’ neo-conservative rollbacks of liberal/left economic policy in Great Britain and the U.S. Hayek championed the primacy of markets over centralized planning; he studied the dynamics of price-setting based on local and personal knowledge and concluded that individually rooted market-based practices were far more efficient than centralized planning driven by government bureaucracies. Influenced by the barbarities perpetrated by the centralized planning efforts of both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Hayek ultimately concluded that the social engineering at the core of centralized planning led inevitably to totalitarianism.

Hayek’s critique of social engineering became an axiom of conservative opposition to centralized planning in the latter half of the 20th century. Yet, ironically, government-directed planning efforts in post-WWII western Europe and the U.S. generated considerable success. Consider, for example, West Germany’s national apprenticeship program, France’s universal early childcare system, flood control and farmland reclamation in the Netherlands, the National Health Service in Great Britain, and in the U.S., southern rural electrification, the legitimation of labor unions and collective bargaining, and the Social Security system. But in spite of these enduring successes, social engineering has become a key focus of conservative animus toward government-directed centralized planning.

Finn characterizes social engineering in public education as “schemes devised by experts and officials confident that they know what’s best for kids and that manipulating who goes where to school is a way to bring about their vision of a better society.” Finn’s article characterizes the District 15 middle school diversity reform as an example of Mayor DeBlasio and Schools Chancellor Carranza’s social engineering efforts to “rooting out every form of selectivity and ‘disparate impact’ in the offerings of the country’s biggest public school system.”

Yet the 1971 Hecht-Calandra New York State law, which mandated entry testing as the sole criterion for admission to Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, and Brooklyn Technical high schools, was a form of legislative social engineering designed to ensure continuing white dominance at those elite NYC schools. Although Finn lauds former Mayor Bloomberg’s education reforms, they were clearly social engineering efforts that replaced a modicum of community decision-making in the city school system with market-based principles of choice, competition, and test-based accountability. Does Finn reserve the social engineering label only for planning efforts he opposes?

Worse, Finn’s use of social engineering to tar the District 15 reform is mistaken, if not bizarre. The district’s actual diversity effort was a remarkable example of a grassroots, bottom-up community engagement process, rather than the top-down bureaucratic planning exercise Finn imagines. It was preceded by more several decades of organizing by activists, parents, and educators struggling to increase diversity in the district’s schools. The NYC Department of Education (DOE) did indeed fund WXY, an urban planning/facilitation group, to coordinate the reform effort. But as the District 15 Diversity Plan’s Final Report states: “The DOE served as a partner and collaborator but left the decision-making for the plan’s recommendations to the Working Group.”

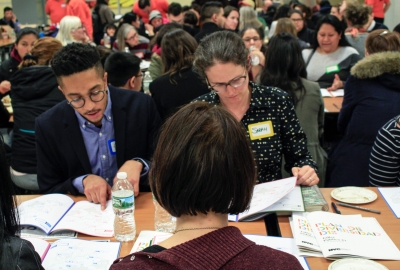

Composed of district parents, education activists, community stakeholders, frontline educators, and administrators, the District 15 Diversity Working Group held four large public planning sessions in district neighborhoods, organized 80 stakeholder meetings including Spanish and Mandarin sessions, distributed a community-wide survey in multiple languages, and maintained a website to post the Working Group’s documents, materials and minutes throughout the planning period.

Group deliberations began in February 2018 and concluded with a final report issued the following July. The Working Group’s recommendations focused on two major areas – Integration and Inclusion. Two key recommendations proposed restructuring middle school admissions policies to enhance integration and improve opportunities to learn, particularly for marginalized student groups and those least well-served by prior district educational policy, by:

- Ending all student screening by the district’s middle schools, including the use of student indicators of attendance, behavior, test scores, report card grades, as well as specific admissions-related testing and auditions;

- Setting admissions priorities for low-income students, English Language Learners, and Students in Temporary Housing at 52% of all seats in each District 15 middle school. (Because these three priority groups are predominantly composed of Black and Latinx students, increasing their representation in all the district’s middle schools would significantly increase diversity and reduce segregation.)

WXY, the planning/facilitation group, engaged parents, education activists, representatives of community-based organizations, and district teachers and administrators in an interactive, intensive and iterative process. The Working Group convened meetings across the district’s neighborhoods to maximize inclusive representation. Working Group sessions analyzed comprehensive and visually interactive data about the district’s schools, student and family demographics, neighborhood housing and income trends, results of previous middle school choice in terms of elementary school to middle school patterns, teacher demographics and other key variables. All data presentations and accompanying materials were translated into the several languages spoken in the district’s neighborhoods, and all Working Group deliberations used simultaneous translation–with headphones–for maximal inclusiveness and clarity of communication. Each meeting alternated large- and small-group presentation and breakout sessions. Note-takers documented all discussions, and minutes of all the previous meetings were distributed to the group’s participants before subsequent meetings and were posted on the Diversity Group’s website.

The Working Group’s practices were not problem-free. The initial planning sessions drew charges of marginalization and tokenism from some district neighborhoods, along with complaints about translation problems and the hurried pace of some breakout groups. But as the process continued, there were fewer complaints, a consistently high degree of participation, and an intensity of frank discussion and analysis that engaged hard questions and generated a raft of powerful recommendations.

After the district’s Community Education Council, the district superintendent and the citywide Department of Education approved the Working Group’s recommendations, the district’s annual middle school application/selection process was reconfigured to reflect the reforms. The initial round of student applications for middle schools under the new policies was held in the fall of 2018, students’ middle school assignments were announced in spring of 2019, and all the district’s middle school students began attending their selected middle schools this past September 2019.

In November 2019, the DOE issued a preliminary report on the impact of District 15’s middle school diversity reform. That report provided the fodder for Finn’s dismissal of the district’s reform effort. Yet the report actually demonstrated some dramatic gains. The District 15 Diversity Plan recommended that by 2021, all the district’s middle schools’ enrollment should comprise 40% to 75% of students from the following priority groups: students living in poverty, students who are Multilingual Learners, and students living in temporary housing. Last year, only three district middle schools met the Diversity Plan’s recommended targets; this current year, under the new reform, eight district middle schools met the targets. Moreover, three of the most high-demand middle schools increased their priority group composition by 33%, 32%, and 15%.

The DOE’s preliminary report also indicated that the demographics of the district’s racial/ethnic populations, and particularly white enrollment, were essentially unchanged from the previous year. (Official enrollment data, including race/ethnicity demographics for all District 15 schools, will be issued in Spring 2020.) However, two hyper-segregated district middle schools posted only small priority group reductions. The Charles O. Dewey middle school went from 95% of its students in the three priority groups to 92%; the other middle school reduced its priority group percentage from 95% to 89%. Though Dewey’s white student intake increased by almost 10%, 29 fewer students enrolled in the school’s incoming 6th grade. Presumably, these data generated Finn’s supposition that a large number of students “evidently shifted into charter or private schools or moved out of District 15 altogether.” Yet Finn’s ultimate judgment, “Bottom line: not much integrating, early signs of middle-class exit,” seems not even tangentially related to the data results for all eleven of the district’s middle schools.

Noting that the previous District 15 middle school selection process produced “unlovely student distributions,” Finn concedes that he is no fan of unfettered school choice, “especially where the good stuff is limited and rationed, competition for it is intense, and families, therefore, must strategize, game the system, and pull strings to produce satisfactory placements for their daughters and sons.” Presumably, he might even accept that these “unlovely distributions” often produce the hyper-segregation in urban school districts that severely limits the opportunity to learn and produces dismal student academic outcomes and stunted life-chances for millions of Black and Latinx students. Finn urges “the creation of lots more quality charters and voucher programs (which New York doesn’t have) so as to boost access to more excellent classrooms for more kids, particularly poor and minority youngsters.” But the research evidence for the academic effectiveness of vouchers is terrible, the results of charter school academic effectiveness are mixed, and thus far charters seem to increase segregation rather than mitigate it.

One might assume that given Finn’s concern to improve access to learning opportunity, “particularly for poor and minority youngsters,” he might be moved to celebrate the initial results of a grass-roots reform that has increased diversity and heightened integration since the research evidence that integration improves schooling outcomes for both marginalized and advantaged students are quite convincing. But on the evidence of Finn’s response to the District 15 reform, one would be wrong.