It is quite common during our work exploring issues of race, power, and privilege with schools around the country for white participants to suggest we should shy away from inflammatory terms like “white privilege.” They assert, by avoiding being provocative, we could rally more folks around efforts to address inequity. Exerting the very privilege they are afraid to discuss, they are looking to use their power in determining what, if at all, they will actually do differently in the interest of racial justice. Ali Michael defines racial competence as:

Having the skills and confidence to engage in healthy and reciprocal cross-racial relationships; to recognize and honor difference without judgment; to notice and analyze racial dynamics as they occur; to confront racism at the individual, group, and systems level; to cultivate support mechanisms for continuing to be involved in anti-racist practice even when it is discouraging or conflictual; to speak one’s mind and be open to feedback on one’s ideas; to ask for feedback about one’s ideas and work; and to raise race questions about oneself and one’s practice (2015).

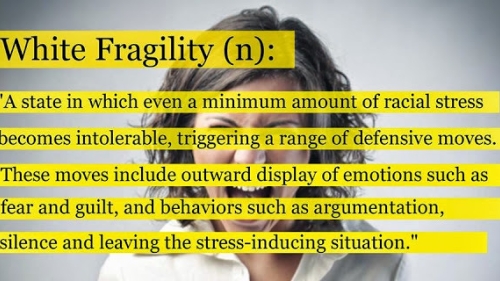

Having this racial competence requires overcoming what Robin DiAngelo terms white fragility.

White Fragility is a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include the outward display of emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence, and leaving the stress-inducing situation (2011).

Overcoming this fragility and fear demands that those who hold the power and privilege in the current system be willing to make sacrifices for change. In PBS’s documentary, The Talk: Race in America, white folks are asked to reconsider being allies and to commit to being accomplices because accomplices risk losing something. The very first loss will be some level of comfort. When we become used to the status quo, any deviation from it can shake us up. Make us feel a certain way. This is often the fork in the road that determines the real level of depth and transformation a school or district can attain. The goal of promoting a positive climate for racially, culturally, and linguistically diverse students and staff means disrupting and dismantling existing systems that privilege whiteness as power.

Michael (2015) suggests, “You can have a multicultural curriculum and still not have an anti-racist classroom” (2015, p. 2). You can say you believe in equity and even mean it, and still not be anti-racist. You can profess your allyship for people of color, but never be willing to do the deeply personal, revolutionary work of moving beyond your fragility and fear in fighting for racial justice. So, to those folks who ask us not to discuss the uncomfortable, not to name what must be named, I ask, “Then what really, if anything, are you willing to lose in this fight? How much does it mean to you and how much are you willing to sacrifice?” Only you know the answer.