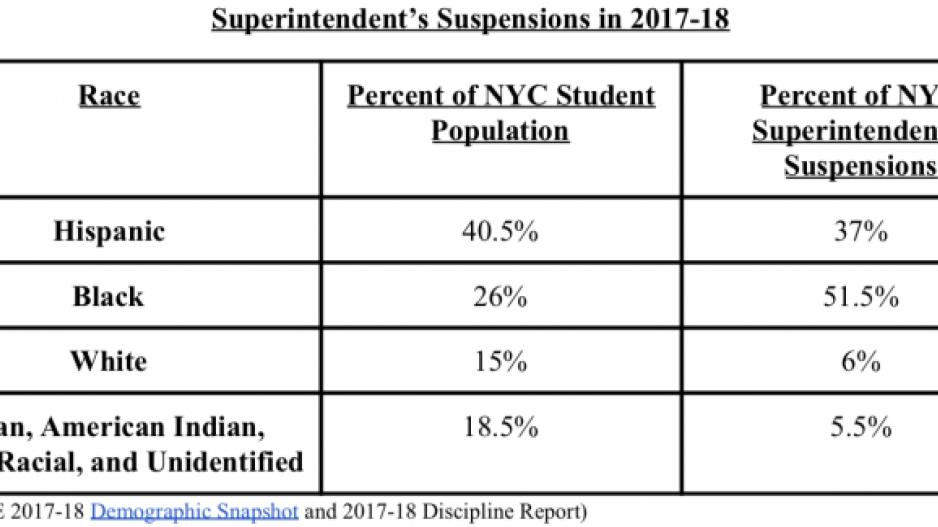

The New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE) recently released its annual data report on school discipline for the 2017-2018 school year. Following a trend of three consecutive years since data have been reported, Black and Latinx New York City public school students were once again disproportionately suspended last school year. Despite comprising 67 percent of the NYC student population, Black and Latinx students were issued almost 90 percent of all superintendent suspensions during the 2017-18 school year. A superintendent suspension is issued for serious behaviors and can be for a period of up to 180 days, with a mandatory minimum of five days. With the current disciplinary policies, students in New York City can be suspended for up to an entire academic school year, 180 days. This punitive discipline policy with racially disproportionate effects is not unique to New York City. Students throughout the US share similar disproportionate disciplinary outcomes due to racialized experiences.

The current NYC DOE discipline policies harshly punish and criminalize Black and Latinx students for behaviors not deemed appropriate. Given the alarming number of Black and Latinx children who are handed down a superintendent suspension in one school year, the conversation around the intersection of education and school discipline is one that must include race.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings crafted the often-cited understanding of culturally responsive education (CRE) in the context of Black students. Many of CRE’s tenets focus on students’ cultures as central to their educational process and teachers’ pedagogical process; they highlight inclusivity in all aspects of education, not just pedagogy. CRE also includes ways of learning, positive community and family engagement, student-centered learning, and a reshaping of the curriculum to incorporate a purposeful inclusion of students’ backgrounds. Moreover, it includes a shift in educators’ and administrators’ mindsets.

In the context of discipline policies, cultural responsiveness can manifest in an overhaul of classroom and schoolwide rules that currently contribute to the high rates of suspension for Black and Latinx students. By dismantling the power structure between educator and student (which includes interrogating the lopsidedness of an overwhelmingly white and female American teaching force compared to a predominantly Black and Latinx student population) and allowing students to be participatory in the development and execution of disciplinary policies, schools could vastly shift the narrative for many of the NYC students who face high rates of suspension. Some schools have already begun this process, creating restorative circles and review boards comprised of students and administrators that examine infractions before deciding on a punishment. However, this is not a practice that is implemented throughout the city.

Many NYC public schools craft and execute discipline policies from a deficit-based perspective, believing that students need to be corrected in some way or their skills and behaviors need to be altered to conform to societal norms. This mindset results in continued racial disproportionality. Educators’ mindsets and actions should use an asset-based lens. Asset-based thinking understands that the cultures and behaviors of marginalized communities, in this case, Black and Latinx students, are strengths to be championed.

However, CRE alone is not a panacea for the racial disproportionality in discipline outcomes that have been systemically and historically rampant in New York City schools. CRE cannot and will not serve as a cure-all for the institutional racism that Black and Latinx students currently face in their schools. Additional work, such as educators engaging in self-examination to find and address implicit biases that may contribute to these outcomes, must be done.

Viewing the table above through a CRE lens, New York City Black and Latinx students attend school in environments that severely criminalize them. Every time their actions don’t align with a, sometimes overly subjective, school code of conduct, they are heavily penalized with the issuance of a suspension. With a superintendent suspension, there is little room for second chances. You may miss an entire school year. You may miss 180 days of peer engagement, social development opportunities, and moments of connectedness with teachers. What are we teaching our Black and Latinx students with the looming threat of the superintendent suspension? For what futures are we preparing them?