Too many of us educators have been given a pass in relation to our obligation to help end the suffering of hurting women, men, and children languishing across the globe. Their screams to us for justice are shrilling, piercing through the night air like the shadows of bullets cutting through Black and Brown flesh—innocent people suffering and dying too soon, and sometimes at the hands of states because the state have so deemed Black, Brown, poor, and indigenous lives expendable.

In recent months, scenes of state-sanctioned violence have erupted in Venezuela, painting an eerily familiar picture—one that portrays violence as systemic, linked to the preservation of the state, rooted deeply in global systems of oppression (think St. Louis, Baltimore, Detroit, Chicago, etc.), and driven to maintain the suffering of Black, Brown, indigenous, and poor people. Like in urban and rural geographies across the United States—from Chicago to Camden—violence throughout the globe—from Caracas to Cape Town—for the vulnerable appears as a constant reality reflected against those who find themselves positioned as objects as opposed to subjects of the state.

In Caracas (the capital city of Venezuela), for example, there were an estimated 2,690 homicides in 2015 (more than three times the number of homicides in Chicago, a city of similar size and perdition).[1] Regardless of the location, suffering among the vulnerable—individuals and groups marked as Black, Brown, poor, queer, etc.—is pandemic, and the state plays a role in its maintenance. As critical educators, we have forced ourselves to ask: how might we reframe our understandings of education to combat the state and protect the people? In sum, how might classrooms function as sites of possibility to help end state-sanctioned violence and human suffering?

The master narrative surrounding such violence often indicts the people; however, what is frequently seen as civilian crime cannot be considered simply a matter of broken morality or unfortunate circumstances. In both the U.S. and Venezuela, state violence is in chronic redesign through laws that disenfranchise and institutions that first create and then target vulnerable people.

Though the homicide rate in Venezuela may seem stark in comparison to that of the US, given the systematic disenfranchisement of African Americans and Latinx, and the ongoing historical genocide of mass populations of people indigenous to the western hemisphere, it is disturbingly predictable that homicides in the US, like homicides in Venezuela, are concentrated in places most inhabited by Black, Brown, indigenous, and poor people.[2]

A comparative understanding of state violence is limited on its own, for violence is not only sanctioned within states but also between them. In this light, we understand colonialism as a global project pledged to violent regimes; thus, we must look at the ways that violence within and between states are currently sustained by international organizations, international media, foreign aid, and other mechanisms that create international hostilities and oppressions. It is only through this comparative and global examination of violence that one is allowed to see the various ways in which states exert force as part of their inherent function of maximum control. Thus, at its most basic level, violence is not only an act of control, it is also “the essence of the state.”[3]

Regardless which purpose of education a state elects, the conclusion of education framed in terms agnostic to state hostility is sadly the same: more violence, more incarceration, more forms of human internment and fugitivity, more premature death and man-made famines, more poverty, more poisoned water supplies, sustained inequities, and more government regimes that choose not serve their people but instead terrorize them.

In this state of current global affairs, the problem should never be seen as the people, nor can it be confined to any given economic system. The problem is the culture of government, any government for that matter, that chooses to oppress people as a way of affirming its control. Unfortunately, those who are most at risk of state-sanctioned terror are conditioned within and by the system. According to Marc Lamont Hill, this conditioning has “only increased their vulnerability, making the lives of vulnerable people less rather than more safe.”[4]

We don’t have to look far to find evidence of the rise of vulnerability. It is all around us. It echoes in the tragic cadences of “Black lives matter”; in the ominous cries of Eric Garner: “I can’t breathe”; and loudly in the screams of Venezuelans marching the streets of Caracas shouting, “We are hungry!” If there is one point to be made in this post, it is this: We educators can no longer turn deaf ears to the deafening cries of hurting people when in our hands we hold the very keys from which people might gain freedom from violence and suffering.

Educators must join the people in our campaign for more freedom. According to Paulo Freire, the greatest humanistic and historical task of the oppressed is to learn in ways that allow them to liberate themselves. Thus, education for liberation requires deep study and contemplation that can only be meaningful if it transcends thinking confined to borders, which are hegemonic by definition.

Liberating education must “consists in acts of cognition, not transferals of information,” where the eradication of state-sanctioned violence will involve first a commitment to understanding the reasons and ways violence is exerted and also experienced. Further, classrooms are the natural place where this type of study is possible, and yet the most critical site of education—schools—are part of an establishment sanctioned by the same state that sanctions violence. Nonetheless, schools have a unique positionality in the eradication of state-sanctioned violence in that they are squarely planted within the contexts of the state (schools, too, adhere to policies and practices that systematically disenfranchise the Black, Brown, indigenous, and poor bodies made vulnerable by their national and international oppressors) and yet their content may be the only location of liberation from the state.

In this light, we urge educators who see themselves as learners to view borders—the space between freedom and oppression, between schooling to subjugate and schooling to liberate—as tools that seek to limit our understandings of human suffering and to stifle our efforts to eradicate oppression and its affinity to produce vulnerability. Thinking, advocating, educating, within the confines of borders, as using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house, will only lead us to know what we already know to be clear: Borders serve to blind us from our own human experience; they divide and conquer our minds and bodies; and they force us to be players in the reproduction of global inequalities.

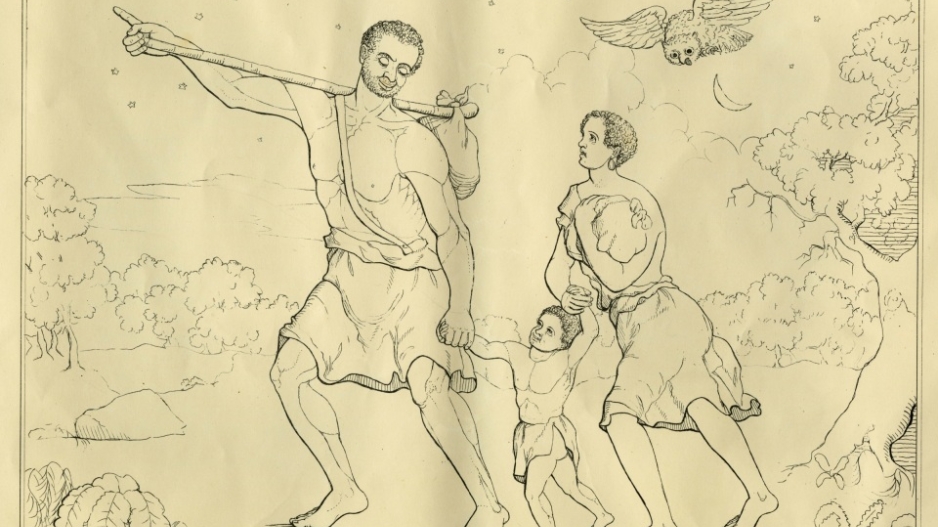

We educators must therefore explore that which inevitably binds us—beyond the construct of borders—and learn the ways our common and eclipsing love for children, for humanity, and our rejection of the production of human suffering form part of that binding. We must continue to explore, in the face of global violence supported by those supposedly charged with protecting us, how might we understand that education should always, and first, be about peace in the space of discord, about healing for the wounded, and about freedom for the captive. How might we reimagine our jobs as educators as joining these struggles to end the pandemic of human suffering and paving a new way with education for liberation that sees teaching and learning as sites of joy, love, and curiosity? Finally, how do we locate liberatory education as a force for good in a world so desperately in need of it to shield and protect our children as they march closer to their own North Stars?

Notes:

[1] Monitor de Homicidios. (n.d.). [Data base of publicly available homicide rates worldwide]. Igarapé institute. Retrieved from: https://homicide.igarape.org.br/?l=es

[2] In the U.S. the highest homicide rates occur in the following 10 cities (all of which are predominantly or considerably Black or Brown according the 2010 U.S. Census): St. Louis, Baltimore, Detroit, New Orleans, Newark, Cleveland, Orlando, Memphis, Chicago, and Kansas City (Monitor de Homicidios, n.d.).

[3] Alimahomed-Wilson, J., & Williams, D. (2016). State violence, social control, and resistance. Journal of Social Justice, 6, 3

[4] Hill, M. L. (2016). Nobody: Casualties of America’s war on the vulnerable, from Ferguson to Flint and beyond. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Authors:

David E. Kirkland is the Executive Director of the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, and an associate professor of English and urban education at New York University. Dr. Kirkland can be reached by email at: davidekirkland@gmail.com.

Pamela D’Andrea Montalbano is a research scientist for the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, and an adjunct professor at New York University. She can be reached by email at: pamela.montalbano@nyu.edu