by Kaitlin Noss, Shabnam Javdani, and Dylan Brown

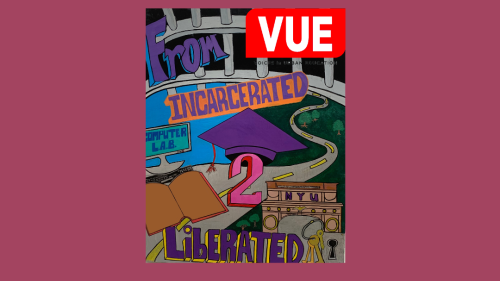

As guest editors of the latest issue of Voices in Urban Education (VUE), New York University’s Prison Education Program (NYU PEP) team welcomed the opportunity to contribute to NYU Metro Center’s long-standing open-access journal. This special edition of VUE, Volume 53, Issue 1, titled Abolitionist Praxis and Education Across Prison Walls, provided the NYU PEP team with the opportunity to collectively think deeply about the contradictions and intersections between education and incarceration. Our thoughts are shared within the blog post below.

Our work as faculty and staff at the New York University Prison Education Program (PEP) puts us squarely in the tense nexus of these spaces as we accompany students along their paths in and beyond higher education, within and beyond carceral walls. We have learned with students about the radical importance of access to the basic human right of education in carceral settings. That is, the right to time, space, and resources that enable people to gather for the purpose of thinking critically, reflecting together, and transforming our consciousness in order to transform our world.

The Struggle for Expanding Access to Prison Education

People incarcerated in New York facilities from Attica to Bedford Hills have organized their demands for access to higher education for decades, and the growing landscape of higher education in our state is a direct result of their vision and determination. Imprisoned people and comrades on the outside have also long used education to advance a joint struggle for collective self-determination and as a strategy in the movement to abolish policing, imprisonment, and surveillance. We certainly do not believe ‘formal’ education–meaning accredited by a degree-granting entity–is either necessary or better than the myriad forms of popular and political -; .education. But we acknowledge that University-based education offers a specific tactic of institutional access and resources, as well as the critical tool of a completed degree that opens doors to employment, housing, and even extended life expectancy (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2025.)

Does education behind bars reinforce the prison-industrial complex?

Universities can and do play a role in reproducing the prison industrial complex, through research, technological development, and the expansion of police power on campuses and surrounding areas. The very presence of Universities inside prisons may help to legitimize the carceral state as ration” (as many ‘correctional education’ programs espouse) or at the very least one that can be reformed and made more humanitarian. From our vantage point within a University, we are intimately familiar with {the distinct set of contradictions, tensions, and questions that college-in-prison programs raise for abolitionists. In fact, as abolitionists we are at odds with those conceptions of college-in-prison, and yet we navigate the murkiness of this work to greater and lesser effect in day-by-day decisions that require a constant refinement of our abolitionist compass. At its founding, our program sought guidance from the staff and students at the Education Justice Project of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, whose critical inquiry still guides our work: “How do we argue for expansion of higher education in prisons across the state, while at the same time insisting on the need to close prisons?” (Education Justice Project, 2025).

Confronting the contradictions of Prison Education Programs

This edition of VUE presents a breadth of responses to the tensions alive in this question from students, teachers, organizers, and scholars. We consider the renewal of foundation and state support for US college-in-prison programs within the neoliberal context of policies that gut education from kindergarten to college while ever-expanding the world’s largest prison and policing regime. As our society continues to prioritize punishment over learning and care, schools themselves are also reconfigured into carceral spaces. Policing in schools has spread throughout K-12 and higher education systems in the US disproportionately targeting students of color, Black girls in particular seeing the highest relative rates of suspension, expulsion, and arrest at school starting as early as kindergarten (Epstein et al., 2020). Beyond pushout, educators and students are now forced to navigate increasing attacks and censorship, including hundreds of educational gag orders, restricting the teaching of Queer, Trans, Black and Indigenous histories in classrooms at all levels (PEN America’s Censored Classrooms, 2024). On University campuses particularly, faculty and student organizers have raised the alarm about punitive disciplinary processes and partnerships with local police departments to curb free speech and dissent.

VUE’s Abolitionist Praxis and Education Across Prison Walls Issue

Given this current terrain, in this issue of VUE we highlight narratives that see education and access to spaces of learning as a transformative and necessary part of freedom dreaming and freedom making. Abolitionist educators outside of prison describe their pedagogical approaches, college-in-prison professors narrate their misgivings and challenges, students outline their experiences and theories, and scholar-activists detail critical connections between student protests and broader social movements. We invite readers to read, reflect, and think with us as we attempt to live the questions of our moment and practice toward the world we want and need.

Kaitlin Noss is the Executive Director of New York University's Prison Education Program (PEP).

Dylan Brown is the Associate Director of New York University's Prison Education Program (PEP).