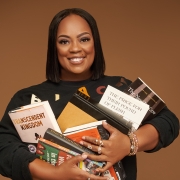

Crystal Martin, PhD

Before I knew the word institution, I knew the smell of Pine-Sol and pound cake. I knew the velvet hush of deep burgundy sanctuary carpets beneath my shoes, the flicker of a row of chandeliers casting light onto my skin like a secret blessing. My earliest lessons didn’t begin in a classroom. They began in the Black Church, a community institution.

Before I ever studied institutions, I was already being shaped by one, not through mandates or metrics, but through memory, rhythm, and the radical act of showing up. Even sacred spaces carry contradictions. But at their best, they teach us how belonging is built, not by policy, but by presence. Not through hierarchy or metrics, but through relationships, memory, and shared purpose.

The Black Church was the first institution that held me. Body, spirit, and story.

I come from a long line of Black preachers from the south and midwest. Though I was born not with a sermon in my mouth, but with “too many questions”. My father was the drummer—steady, unrelenting, anchoring the spirit’s flight with rhythm. My mother conjured beauty from fabric and flowers, turning fellowship halls into gardens. Uncle Henry, who was everybody’s uncle and nobody’s kin, sold candy from the back of his van after service. A silver change machine swung from his hip, clicking and clacking like a gospel tambourine each time it spit out a quarter. That sound still lives in my bones.

This was a cast of characters stitched together by faith, not blood. Aunt Joyce, who kept the bathrooms pristine, wore white gloves on Sundays and carried peppermint in her purse like treasure. Her physical presence was larger than life. Sister Delphine gave every child a quarter—a silent agreement that it would soon find its way back to Uncle Henry in exchange for a small box of Lemonheads or a bag of chips. These were the institutional rituals that taught me economy, reciprocity, and joy.

We spent whole days there, mornings slipping into afternoons, slipping into evening praise. I’d sometimes fall asleep under folding chairs, lulled by the hum of voices and the smell of fried fish from the kitchen. When I woke, they’d still be dancing, still singing, still praising. The Church, particularly the Black Church was not a moment in time—it was a world unto itself.

It was here I first learned how institutions breathe. Not just through rules, but through rhythm. Through memory. Through shared intention. We weren’t just attendees; we were contributors. Choir rehearsals, bathroom duty, Sunday school snacks—every task was sacred. My own contribution was song—my small voice lifted in the choir, stitched into a chorus of belonging.

Back then, (as a child growing up in the Black Church), I thought we were all related. And in a way, we were. This is where people met and married, where babies were blessed, where grief was held in the arms of elders. It tangled our roots and blurred the boundaries between us. We became family by showing up, by circling back, by doing the work of holding one another.

Like any institution, the church is not without contradiction. It has, at times, excluded even as it sought to embrace. But for so many Black people across generations, the Black Church has also been one of the few places where we could breathe fully, speak freely, and be held wholly. It has been a site of resistance and refuge, a space where our humanity was affirmed in a world determined to deny it. It taught me that institutions at their best don’t just create structure. They create a feeling of “home” and offer an inclusive sense of welcoming and belonging.

Essential Questions about Institutions:

- What institutions held you before you had language for them?

- What did they teach you, not just about belonging, but about culture?

- About whose traditions were honored, whose stories were told, and what forms of knowing were recognized as legitimate?

I ask because if we are serious about transforming education (or any system) we must begin not with data, but with memory. With people. With place. With a deep commitment to creating spaces where everyone feels they matter and belong—but also where their cultures are centered, not just included.

Belonging is more than being welcomed; it’s the feeling of being expected. Of knowing that your presence, your voice, your story is not an afterthought but part of the foundation. True belonging is built through recognition, ritual, and relationship—it is culture in motion."

This is the foundation of my work on freedom dreaming and it’s also at the heart of culturally responsive teaching. Gloria Ladson-Billings reminds us that teaching must center not only academic success, but also cultural competence and critical consciousness. Culturally responsive teaching challenges us to treat culture as curriculum and memory as method. Treating memory as a method means honoring memory (not just as anecdote or nostalgia) but as a legitimate, rigorous, and transformative way of knowing.

It’s a methodological stance that says personal, communal, and cultural memories hold power: they can guide how we research, teach, learn, and dream new futures into being. It invites us to design schools the way many of us first learned to belong—not through metrics, but through meaning."

For me, that space was the Black Church. For you, it might have been somewhere else—a baseball team, a tenants’ association, a community kitchen, the stoop where everyone gathered after school. Maybe it was a corner store, a cousin’s living room, or a classroom that felt more like a sanctuary. Whatever that space was, it shaped you. It taught you something about how institutions hold us—or fail to.

In the next blog post of this series, I’ll explore how these early insights about community and infrastructure are shaping my current research on schools, teacher well-being, and the role of community institutions in sustainable educational transformation.

Until then, I invite you to reflect:

- Where did you first experience a sense of belonging—not just being welcomed, but being known?

- What forms of knowledge and culture were honored in that space?

- Who felt centered there, and who might have been left at the margins?

- How might those early lessons challenge dominant narratives about what education should look like—and who it should serve?

Because memory doesn’t just recall the past—it helps us reimagine the future.

Are you truly interested in building Welcoming, Affirming, and Healing Schools? Do not miss the EQUITY NOW conference on Friday, May 30th, 2025. This critical conference offers a full day of community building, networking and learning for educators, parent/caregivers, youth, community organizers and technical assistance providers who are committing to transforming their classrooms, schools and districts. All will walk away with clear next steps on what transformational education looks like when children, families, educators and community experience welcoming, affirming, healing and liberatory spaces.