“Meredith thinks you should take a Xanax,” my girlfriend told me, looking up from her phone. “I told her you already did.”

“Did you tell her that 11 million people are in lockdown in Northern Italy?” I said. “That you can no longer leave or enter Milan?”

I could have gone on. “Did you tell her the U.S. has only tested 2,000 people? That South Korea tested 65,000 in the first week?”

“No baby, I didn’t tell her. It’s her bachelorette party. I don’t want to upset her. Plus, she doesn’t think we’re at risk.”

A week later, the party was canceled. Americans all over the country are changing their behavior. In New York City, where I live, many people are working from home. Bars and restaurants have closed. Similar steps have been taken across the country. “Social distancing” has entered the national lexicon.

Still, the first week or so of lockdowns brought a stream of reports from across the country of full restaurants and packed bars. A clip of a raucous country concert went viral with the caption “Downtown Nashville is undefeated,” and the governor of Oklahoma tweeted a picture of his family at a crowded restaurant with the hashtag #supportlocal. Beaches in Florida were packed shoulder to shoulder with Spring breakers. “Masque of the Red Death,” one journalist quipped.

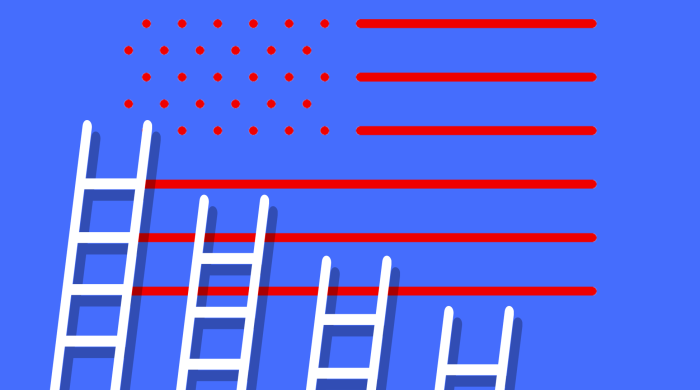

The main tool against coronavirus, social distancing, is a collective action, a behavior taken in the interest of the group. As someone who studies the reasons people take part in collective action (and the reasons they don’t), I have been trying to make sense of the American people’s partial and inadequate response. Even as social distancing becomes less a matter of individual choice and more a matter of state policy, this remains an important issue. Because, by many accounts, we are about to enter a period of American history where far more individual sacrifice and cooperation will be needed than what the government can or will mandate.

Two theories appear to be winning out in the media, both of which frame the problem as a failing of individual psychology. The first is ignorance, including, in some cases, the willful variety. The second is selfishness. In particular, I see this charge being waged against young people. There is a strong “kids these days” flavor to these criticisms. As one tweeter put it, sacrificing for your country used to mean dying in the mud, now it means watching Netflix on your couch.

Even as a student of the psychology of collective action, I think the focus on psychological shortcomings is unfortunate. Psychology matters a lot for behavior, and people are indeed more likely to take part in collective action when they recognize the need and when they feel morally compelled. But psychology does not develop in a vacuum. It is powerfully shaped by the social environments we inhabit. More attention on the failings of weaknesses in social environments can give a more complete picture of the problem.

It should also be more useful given that focusing on the environmental, rather than individual, levers of collective action, is a more effective and efficient promotion strategy. The metaphor of the broken dam illustrates the power of environmental vs individual interventions: you save a lot more lives putting houses on stilts than you do fishing people out of the river.

Social environment is an admittedly vague term. Let me clarify what I mean by it. What I do not mean is the overarching cultural climate, whether the nation’s, or that of any generation or group within it. To the extent that the commentariat has an social-environmental explanation for social distancing laggards, it has been based on these types of environments, particularly the supposedly blanket individualism of American culture. The social environments I am interested in are far more concrete. They are the social environments that structure daily life and our relationships: workplaces, schools, neighborhoods, places of worship, etc.

Something as fundamental as the notion of selfhood can vary depending on the immediate social environment. One of the more popularized findings of social psychology is that while Americans tend to think of themselves as autonomous human units (independent selves), East Asians tend to think of themselves as more fundamentally relational entities (interdependent selves). Originally, the most accepted explanation for this was broad civilizational differences in disposition. But subsequent research suggested that social environments might play an important role. For instance, a study in Science found that Chinese people from traditionally wheat-farming regions looked a lot more like Americans in terms of independent selfhood than Chinese people from traditionally rice-farming regions. Why? Well, while rice-farming requires intense collaboration, wheat-farming is a mostly solitary job. As this example illustrates, if we are too quick to look for explanations for behavior in the cloudy domain of culture, we risk overlooking the action at the ground-level.

So what is it about certain American social environments that has failed to sufficiently cultivate the psychological raw material for collective action at this time? One answer is that many American social environments do a poor job incentivizing collective action. Let me explain.

It may be hard to fathom right now, given the precipitous drop in human contact over the past weeks, but pre-coronavirus America was already suffering a social disconnection crisis. The roots of this crisis have been debated. Potential culprits include the decades long decline of civil society and organized labor, the decline or postponement of marriage and family, the evaporation of organized religion, and the workplace’s insidious ascendance to social environment-in-chief. What is not debated, clearly, is the crisis’ roots in social environments. For individual Americans, this crisis manifests as low social embeddedness, which means less involvement in the lives of others, and less involvement in meaningful group activity. As a recent survey found, over 40% of Americans report that they go full days without meaningful face-to-face interaction.

Generally speaking, the less socially-embedded people are, the less collective action is in their self-interest. The economist Mancur Olsen famously argued that, under many circumstances, collective action was not in the self-interest interest of the individual. The example of a fishery shared by a group of fishermen can illustrate his point. It is obviously in the group’s benefit to fish sustainably, so that the fish replenish and the fishery can be relied on for years to come. But, each individual also has the incentive to maximize profits by catching as many fish as possible. Situations such as this, where group and individual incentives conflict, are known as collective action problems. Under this particular collective action problem, the most rational course of action is to overfish and leave it to others to follow the rules, what is known as free-riding.

Luckily this scenario leaves out a key variable: relationships. Oh right, those. For example, maybe there is a fishermen’s organization with a regular meeting place, and maybe through this organization the fishermen develop close friendships, get to know each other’s families, even organize to fight common adversaries (e.g. polluters). It also fails to recognize the remarkable power of social environments to transform the meaning of self-interest so that it aligns more closely with the interests of the group. Psychologically speaking, there are several reasons this might occur. For example, feeling good about one’s self is a core human need. For the purely atomized fisherman, personal profit might indeed be the primary source of self-regard. But for the socially embedded fisherman, his fellow fishermen’s perceptions of him may be equally if not more important. As this illustrates, social environments with high levels of socially-embeddedness have the ability to impose costs for failing to act in group interests. In addition to a loss of social standing, these costs might include the loss of various other benefits afforded by the community: friendship, social support, free childcare, etc.

With this example in mind, there are at least two ways we might trace inadequate social distancing back to the weaknesses of American social environments. The first relates to the specific form of collective action in question. While many forms of collective action — protesting, fundraising, community organizing — involve significant social interaction, social distancing requires a lack of it. Under conditions of un- or undermet social needs, the individual costs of such a behavior increase. A good friend of mine just broke up with his girlfriend of 10-years, and has been struggling seriously with his mental health ever since. He went out last Friday night, to a crowded bar in Brooklyn. When I reprimanded him, he said, “I can’t spend the next two months by myself.” Such costs are not necessarily negligible when weighed against threats of infection. As Ezra Klein warns, protracted social distancing measures are likely to exacerbate the negative effects of the existing social disconnection crisis, including addiction and suicide. The state of America’s social environments may be pulling self and group interests further apart as a time when we need them to move closer.

Social embeddedness may be particularly important for motivating high cost collective action. During the height of the Civil Rights Movement, busloads of Northern college students made the trip to the Deep South to register black voters and otherwise assist in the struggle. This was a highly costly activity from the standpoint of time, money, and personal safety, as many “freedom riders” were attacked and several killed. The sociologist Doug McAdam examined the reasons why some volunteers were willing to withstand these costs while others dropped out, and found that the volunteers most likely to persist were those with the greatest number of strong social ties to others in the movement.

This leads into the second reason for viewing poor social distancing as an outcome of weak social environments. Socially disconnected people are less subject to social pressure — to norms, in other words. Scroll through your Twitter feed these days and it shouldn’t be too long before you come across a post ‘calling-out’ Americans for attending a church service or participating in a St. Patrick's Day bar crawl. The shame may be warranted but, as the Great Culture War has no doubt taught us, shame wielded by strangers is a poor tool for influencing behavior. People are more likely to respond to the cajoling of those they have valued relationships with. It especially helps to be embedded in social environments where there is significant moral consensus. Strong agreed-upon moral norms fused with high social connectivity form a powerful tool of social influence, as individuals can safely anticipate social rewards for following the norms and social costs for violating them.

Of course, I have left out the possibility for people to be embedded in social environments that lack a proper norm. As it relates to social distancing, this is likely the case for certain pockets of arch-conservatism. But college campuses also strike me as another candidate. Campuses in the heaviest hit areas have since been shut down, with many students moving back home temporarily, but anecdotal evidence (first-hand included) makes me doubt whether many campus watering-holes would have lost much business in the absence of administrative action. I suspect this problem may be rooted in another form of social disconnection: the disconnection between social environments. The cloistered, island-like nature of many college campuses makes it possible for students to live out their 4-years without establishing meaningful social relationships to, and responsibility for, members of the surrounding communities. That campuses are deep reserves of moral sentiment and idealism only underlies the failure of these social environments to harness those sentiments in service of local needs. Lest it seem like I am picking on the youth, this problem of inter-environmental disconnect is evident across the country. Racial segregation is perhaps the most damning example, but as it relates to coronavirus, one sticks out even more: the systematic isolation of the elderly. How would the response to COVID-19 have been different, I wonder, if a majority of Americans under 40 had regular, meaningful interactions with someone over 80?

“Our country wasn’t built to be shut down,” President Trump just said. I agree. But while the President seems to have meant this as an allusion to America’s indomitable productive and commercial capacity. I mean something different. What I mean is that America is not built for solidarity. Furthermore, the dearth of solidarity is not just rooted in some national frontier spirit, as some would suggest, but in the frailty of our communities.

Let the great embeddening begin.

Published on March 30, 2020. Samuel Freel is a Doctoral Student in Applied Psychology, NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development