Beginning in 1975, federal law guaranteed all U.S. children with disabilities the right to a free and appropriate public education. Building on this law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990 explicitly mandated that students with disabilities be served in the “least restrictive” educational environment—meaning they would have the opportunity to participate in general education settings and learn alongside non-disabled peers for as much of the day as possible.

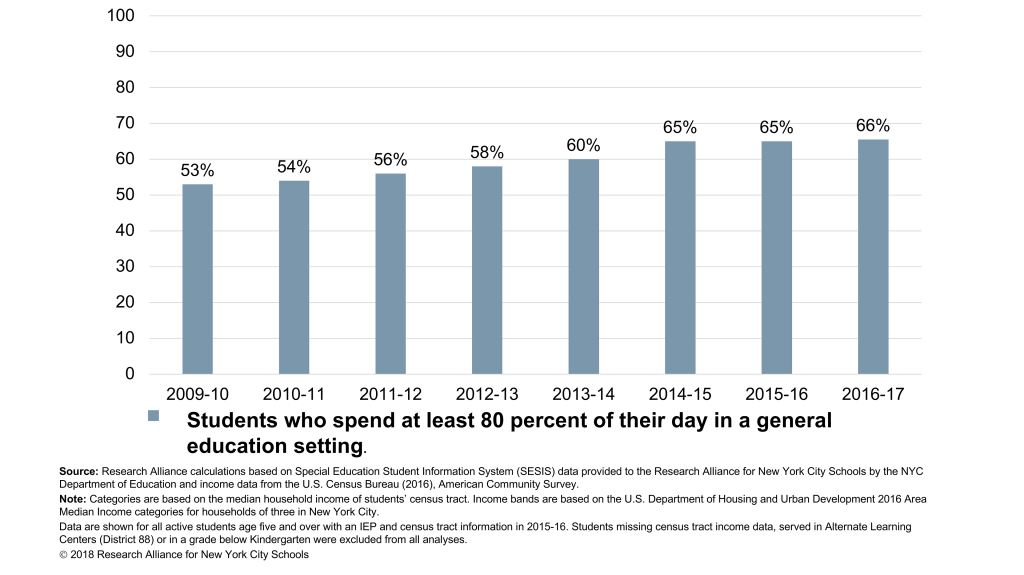

In NYC, the launch of the Shared Pathways special education reform initiative in 2010 accelerated movement toward greater inclusion of students with disabilities in general education settings. Figure 1 below shows the percentage of students with disabilities who were served in inclusive settings for 80 percent or more of the school day, and how this changed between the 2009-2010 school year and the 2016-2017 school year.

Figure 1: The percent of students with disabilities who are in inclusive settings for 80 percent or more of the school day has increased steadily.

In 2009-2010, a little over half of all students with disabilities spent at least 80 percent of their day in a general education setting. By 2016-2017, this increased to two thirds of all students with disabilities. Inclusive settings include Integrated Co-Teaching (ICT) classrooms—where students are co-taught by a special education and general education teacher, with up to 40 percent of students in the class having an IEP—and Special Education Teacher Support Services (SETSS) settings—where students receive personalized support from a special education teacher while in a general education classroom. By contrast, students who are not in an inclusive setting (about a third of students with disabilities in 2016-2017) go to school in a special classroom, where they do not have access to general education peers or curricula.

While a majority of NYC students in special education are now served in inclusive settings for some part of the day (e.g., receiving SETSS or in an ICT classroom), there are substantial differences in placement associated with students’ background characteristics, neighborhood and disability type. For instance, students classified with autism, emotional disturbance and intellectual disabilities are predominately served in non-inclusive settings.[1] Boys, Black and Latino students, and low-income students are also disproportionately served in non-inclusive, special classrooms.

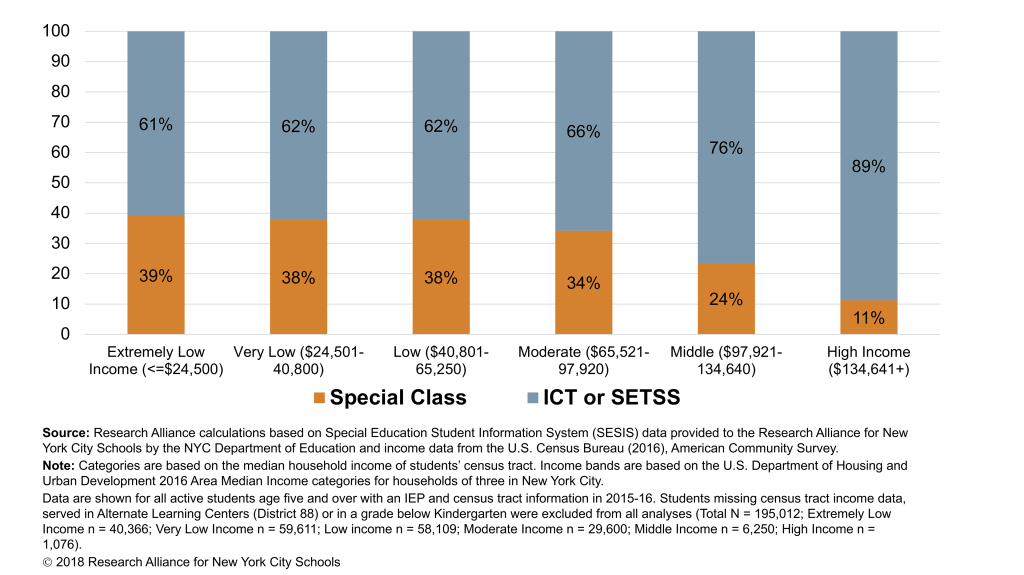

There appears to be a particularly strong relationship between income and the likelihood of being placed in an inclusive setting. Figure 2 below shows the percentage of students being served in an inclusive setting (i.e., SETSS or ICT) based on their neighborhood income.

Figure 2: Students from higher-income neighborhoods are more likely to be placed in an inclusive setting.

Students with disabilities who live in higher-income neighborhoods are more likely to be placed in an inclusive educational environment, compared with students who live in lower-income neighborhoods. We found that less than two thirds of students in low-income neighborhoods are served in inclusive settings, compared with over three quarters of students in middle income neighborhoods and nearly 90 percent of students in high-income neighborhoods.

Big Questions:

These findings raise a number of important questions for future study, including:

- What is driving neighborhood-based disparities in inclusive-setting placements? Are students in lower-income neighborhoods more likely to be classified with disabilities that require self-contained settings? Or are low-income students are more likely to end up in a self-contained setting, regardless of disability type?

- Do NYC students with disabilities in inclusive settings have better outcomes than those in more restrictive settings?

- How does the inclusion of students with disabilities in general education classrooms affect outcomes for other students?

- What are the implications for teachers serving students in inclusive environments, especially in terms of their instructional practices and professional development needs?

What else should we be asking about student with disabilities in NYC public schools? Are you exploring any of these topics? Let us know via email.

This post was authored by Cheri Fancsali and Chelsea Farley of the Research Alliance for NYC Schools. Analytical assistance was provided by Patricia Chou.

This project has been generously supported by the New York Community Trust.

Footnotes

[1] For more information about disability classifications, see the NYC Department of Education’s website.

How to Cite this Spotlight

Fancsali, C., Farley, C. 2018. "What Percentage of NYC's Students with Disabilities are Served in Inclusive Settings? Exploring Equity and Changes Over Time." Spotlight on NYC Schools. Research Alliance for New York City Schools.