How can Gender and Sexuality Alliances (GSAs) support advocacy, health, and critical consciousness? On the Ground spoke to Dr. Paul Poteat (Boston College), Dr. Hirokazu Yoshikawa (NYU), andSarah Rosenbach (NYU IES-PIRT Fellow) about their research, how GSAs can support the healthy development of adolescents, and what role advisors can play in empowering youth. Their responses were edited for clarity and length

When you’re hoping to add a school to your studies, how do pitch your research and work to a Principal or Gender and Sexuality Alliances (GSA) advisor?

Poteat: Schools are facing a number of issues and concerns around bullying and bias-based harassment, and historically that's what my research focused on. I'd go into schools and identify factors that contributed to biased-based bullying and harassment, and principals and administrators would ask, what can we do now to address this? That led me to shift to doing work on GSAs.

Yoshikawa: When Paul, Jerel Calzo [San Diego State University] and I first started this project, we were interested in this emerging positive way to think about sexual and gender minority youth. They’re often viewed solely as victims or affected by disparities — which is true in the sense that there are really serious health and mental health disparities affecting these youth. To counter those one-sided views, it is really great to have this long-standing project where we are looking at positive outcomes for these youth, but also the positive supports and youth-led approaches where they can be actively engaged in leadership and their own developmental potential.

Poteat: I remember talking about the need to contextualize GSAs and to really understand what was going on within GSAs. So much of the early work on GSAs was looking at GSA presence, and does having a GSA in the school relate to relatively better outcomes compared to schools that don't have GSAs? This was really important in making a case for having access to GSAs, but it is not as helpful in understanding what GSAs are doing that is most effective and what we can be promoting in terms of best practices.

Now, when we go to schools and we talk about our work and its relevance, we're able to say there are natural resources that already exist within the school: students, teachers, and administrators involved in the GSA. GSAs are directly addressing issues of bullying and school climate and school belonging. We are really interested in understanding how GSAs work and what makes GSAs effective, so that we can identify best practices to meet a range of needs of youth, maximize their effectiveness, and improve youth’s school climate in general. Whenever Principals or GSA advisors see our work framed that way, they're fairly receptive and see its relevance for addressing their school’s needs.

Your work looks specifically at GSAs in Massachusetts. Are there plans to expand the area of focus?

Rosenbach: Our most recent study was funded by NIH and looked at GSAs in Massachusetts. We currently have an IES grant that has expanded the work to three sites: Massachusetts, New York City, San Diego.

Poteat: It’s been an interesting challenge to see how to do research across many different sites with different policies, yet trying to get at a common question of how GSAs are operating and what specifically they're doing that could be fostering these outcomes of well-being, mental health, and better academic outcomes. They are all in fairly progressive areas, but I still think there are some important differences across Massachusetts, New York, and San Diego.

Since GSAs are youth-led organizations, what role can advisors, teachers, or school administrators play in fostering a supportive GSA environment?

Poteat: I think advisors play a number of roles. Oftentimes, it's a supportive role, connecting youth to resources outside of the GSA, linking them with other LGBTQ supportive agencies in the community for mental health services, getting administrator support for projects, or managing the logistical pieces that youth might not necessarily be aware of.

Rosenbach: It really is a youth-adult partnership. With advisors, there's a wide range of self-efficacy to have discussions on different issues within the GSA. Students might have varying levels of knowledge of resources in the community, and advisors can bring speakers in and play a complementary role with the youth in the GSA.

Poteat: I'm reminded of one of our earlier studies where we looked at youth leadership and advisor leadership. We found that youth who felt they had more control in the GSA reported better outcomes, but youth in GSAs whose advisors thought they, as the advisors, had more control were also reporting better outcomes. It seems contradictory at first, but reflects that they both take ownership and responsibility of the GSA. Maybe they're taking ownership and responsibility over different aspects.

Yoshikawa: Together, the advisors and students in GSAs can create an open climate to discuss topics beyond sexuality or gender identity. Some of our findings show that, in this particular political climate, GSAs can be safe spaces to discuss socio-political issues about immigration or race. We're starting to see that if you have a general space that promotes social justice orientation, and it's also a safe space for sexual and gender minority youth, it may be a space where youth feel comfortable to discuss other issues.

Poteat: Because the project was based on an intersectional lens of how GSAs promote empowerment and wellbeing for youth from many diverse backgrounds, we were interested in how GSAs might bring in discussion of other identities that youth may have. Youth did raise instances where they talked about race and racism and how they grappled with the topics. GSAs provide a safe space that also can hold the tension for youth to have a deeper conversation that isn't superficial, but can be ongoing and sustained. They can talk about differing views and perspectives in a way that's respectful, engaging, and reflective, and try to understand where people align and ultimately promote justice and equity in their schools.

Related Blog Posts:

Q&A: Understanding Black Male Reactions to Police

“Understanding the reactions of Black male youth to police” examined how African American, Black immigrant, and White youth in New York City potentially differ in their assessment of police in terms of threat, security, trust in the police, and identification with the police. Read a Q&A with the project leaders.

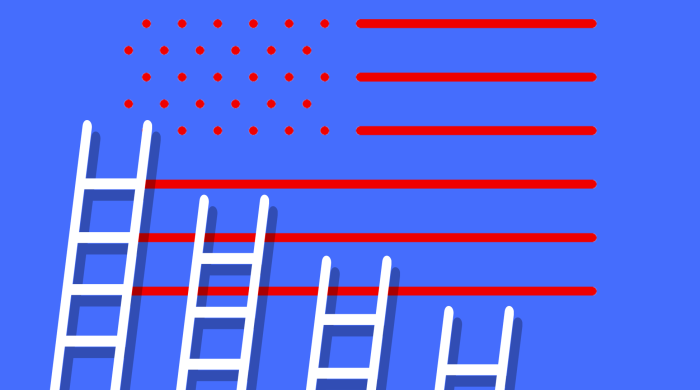

Gauging Americans’ Feelings on Inequality and Social Mobility

How do Americans reconcile their optimistic beliefs about chances for social mobility and economic equality with the day-to-day reality of remarkably unequal distributions of economic rewards and mobility opportunities? Leveraging the power of experimental design and large online surveys, Dr. Siwei Cheng and PhD student Fangqi Wen probed Americans’ often-times paradoxical and puzzling beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions about economic equality and social mobility.

Partnering to Improve Afterschool

What role can afterschool programs play in addressing inequality and promoting opportunities? The Advancing Collaborative Research in Out-of-School Settings (ACROSS) partnership represents a unique partnership between researchers from The Institute of Human Development and Social Change and Good Shepherd Services. Read a Q&A with Dr. Miranda Yates, Dr. Elise Cappella, and Sophia Hwang.