by Tatyana Kleyn, The City College of New York

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned our world inside out, or perhaps outside in (as many of us are forced to stay indoors). Our students have had to deal with trauma, stressors and uncertainty in new and unpredictable ways. Furthermore, Black and Latinx communities have been disproportionately impacted by this virus due to structural breakdowns, and Asian Americans are experiencing increased discrimination and racist attacks as they are wrongfully being blamed for the start of this virus. This means that it is our bilingual students and immigrant families who are bearing a larger burden of the suffering, all while keeping our state and country running in their roles as essential workers. For educators, this reality requires a focus on the socioemotional well-being of students and families.

To get a sense of how educators are supporting their students’ well-being and healing, I sought to learn about the practices of teachers across the nation. After circulating an online questionnaire, I received over 25 responses and have organized them into seven categories:

Taking a Stance of Compassion and Understanding

Teachers across the country are learning, through a lens of compassion, about the new realities our students and their families are living through. María V. Díaz, an educator from the NYS Statewide Language RBERN at NYU explains what taking such a stance looks like in practice:

In working with teachers, one point that I stress is to be compassionate with their students certainly, but also with their families and with themselves. Remote teaching and learning is a new frontier for all of us. Couple that with managing the logistics (inequitable technology, artificial curriculum, lack of scaffolding for our most vulnerable populations), then add families living in tight quarters, financial burdens primarily due to not being able to work, the daily count of deaths that loop the newsreels result in everyone needing socioemotional learning (SEL). So I proclaim being compassionate with everyone. Teachers, it is ok to have activities that take the students away from their screens, parents it is ok not to know how to help your child with 4th grade arithmetic, students it is ok to be sad over missing your school friends.

It is ok! Give yourselves permission to be compassionate and let that compassion reign when we return to the new “normal”.

Consistent and Varied Communication

In the absence of in-person contact, teachers are finding myriad ways to maintain communication with their students and families. Whatsapp, Google Meets, Google Forms, WeChat, Remind, WebEx, phone calls, video calls, text messages, and email are some of the ways they have stayed in contact. Martina Meijer, a 4th grade bilingual teacher at PS 139 also mails postcards to students who do not have access to technology and/or wifi. These communications can serve as a way to learn more about what each family is dealing with, checking in on their well-being, and discussing how learning will take place in order to ease anxiety about virtual learning. Sometimes these communications are to individual students. Ashley, a bilingual teacher checks in on her students to ensure they have eaten, especially if they are home alone. Sometimes teachers reach out to small groups of students to build a sense of community and reconnection with their peers. Colleen, a teacher in Buffalo calls families to check on their needs from food to technology, and emphasizes “I want to know that families and students are okay...we can worry about the work later on!” Jessica Sinchi, a special education teacher of ELA and Social Studies at IS 73Q says, “We usually designate a time everyday and just catch up with one another, ranging from school work to how they’re adjusting because of COVID and so much more.”

Inclusion of Home Languages and Translanguaging

This pandemic has highlighted the importance of access to information, and in some immigrant families, English-only notifications can be an obstacle. Teachers across content areas and programs are finding ways to use home languages to build bridges of understanding. Some teachers are bilingual themselves, while others rely more on translation apps, which aren’t perfect, but are helpful. One teacher explains, “It comforts students and families to know that they can communicate in either language and obtain an understanding of the assignment or resolve an issue.” Maryann Hasso allows her students to read a book in their home language and submit a bilingual summary, thereby lowering the stress of working in a new language exclusively. One teacher has noticed that, “being able to communicate in their own language gives many students and their parents additional emotional support as they are heard and understood during this shelter in time.” By encouraging everyone to use all their linguistic resources, educators are reducing anxieties and making vital information more accessible.

Lessons on Emotions through Literature, Arts and More

Students display emotions through a range of behaviors, often without talking about them or identifying exactly how they are feeling. Michele Damato, a teacher from PS 165, shares, “I provide students with a socioemotional check-in google form each day with a visual feelings chart. This helps me to know how they are feeling and address any concerns with families directly.”

Some schools have lessons that focus explicitly on SEL. Albany International Center School, a secondary newcomers school has a range of SocioEmotional Learning virtual classes. One class uses restorative classroom circle principles and “students also share quotes, songs, and other positive messages to connect with and inspire each other,” Liz Gialanella, the school psychologist explains. Maria Rodriguez, a 4th grade bilingual teacher from PS 239Q has “students meditate and work on different self-care activities to help them manage their emotions and attitudes such as positive affirmations, practicing gratitude, writing down their thoughts, and creating All About Me projects.”

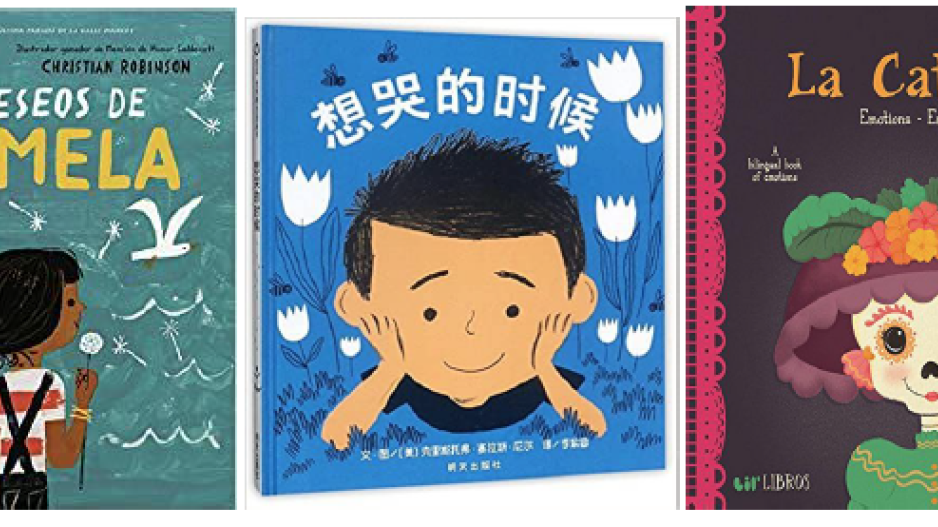

Literature can be a powerful starting point for conversations about one’s feelings and how to approach them. Dayle Pomerantz, an early childhood bilingual teacher says they use “bilingual books for children that speak about feelings [and] encourages children to dictate their words to an adult to draw pictures in a journal.” Here are just a few examples of multilingual books educators can use with their students:

Why We Stay Home is a newly released book that deals directly with the Coronavirus, and can be downloaded for free.

The arts can also be a way for students to deal with challenging circumstances and express their feelings. Pamela Broussard, a High School New Arrival Center Teacher from Houston, Texas had her bilingual students recreate famous artwork via the Getty Museum Challenge. She shares, “I was shocked by the fantastic pieces my students created.

While it was not a part of the assignment, it soon became very obvious that their art choices reflected how they were feeling in regard to COVID-19. They also brought all of us a great deal of smiles and laughter.”

Grounding and Mindful Practices

While many adults have turned to yoga and meditation to get through these times, students can also benefit from these grounding approaches. Alejandra Ramos Gomez is a 1st grade bilingual teacher in Dallas Texas who started a YouTube channel called Aprendamos con Ms. Ramos (Learning with Ms. Ramos). She creates videos in Spanish to “include different science-based mindfulness and meditation practices in a student-friendly format."

Seeking Out Additional Supports and Advocating For Families

Even though they try, teachers cannot do it all! And with a “Maslow before Bloom” mindset, Pamela Broussard says, “ I provide families with links to food banks and food distribution locations.” Angela Timm, an ESL middle school teacher in New Jersey “advocated for access to a bilingual counselor for a student who communicated his fear after hearing that someone close to him tested positive for COVID-19.” And sometimes teachers take matters into their own hands. Sylvia Morse Pachas, an ENL teacher in Buffalo shared that they “delivered a care package to one of my refugee families after I did a videoconference lesson and realized they were lacking a few school essentials.”

Expressing Gratitude

Even in challenging times, it’s important to show gratitude for what we have in our lives and the people who are helping us get through this historic moment. Pedro Calixto is a 5th grade bilingual teacher at PS 169 in Brooklyn who had students write thank you letters to essential workers, in Spanish.

A Note of Gratitude for our Essential Educators

I’d like to conclude by expressing my gratitude to the educators who took time out of their stressful quarantined lives to share what they are doing to support the socioemotional well-being of their bilingual and immigrant students and families. Their extraordinary efforts remind us that we must also make time to care for our teachers, as they are being stretched thin and asked to do their job in a context for which they were not prepared. Yet, they make miracles happen every day by caring for students in big and small ways, as they themselves struggle to make sense of our new COVID context. And to each of these teachers, I say gracias, благодарю вас and mèsi.