To situate findings from this evaluation in a broader context, we root our data collection, analysis, and findings in theories on de-tracking, implementation of major educational reforms, and Critical Race Theory.

A review of research on de-tracking efforts reveals that simultaneous changes in three areas are necessary for de-tracking to be successful:

- instruction

- institutional structures

- beliefs.

Instruction should provide opportunities for diverse ways of learning, keep learners actively involved, provide support for individuals as needed, and create a safe and respectful learning community (Rubin, 2006). Institutional structures should allow for more time and resources for teacher professional development, collaborative time, and instructional retooling and should enable additional social and academic supports for students. Finally, belief systems should shift among educators, students, and families, whereby these stakeholder groups come to believe that all students can learn and engage in rigorous coursework.

When implementing large-scale reforms in schools, such as de-tracking, it is crucial to ask not just whether or not the reform worked, but also what conditions facilitated or impeded the success and sustainability of the reform. A longitudinal study across 22 Chicago elementary schools suggests that 5 “essential supports” contribute to school improvement over time (Bryk et al., 2010). These include:

- School leadership: e.g. teacher leadership, parent and community involvement, program coherence, and instructional leadership

- Parent-school-community ties: e.g. teachers’ knowledge about student culture and the local community and family engagement practices

- Professional capacity: e.g. quality of human resources, quality of professional development, professional dispositions, and professional community

- Student-centered learning climate: e.g. safety and order, teachers’ academic press and personalism, and supportive peer norms

- Instructional guidance: e.g. curriculum alignment, intellectual emphasis and pedagogical methods.

Bryk and colleagues (2010) found that schools strong on at least three of the five essentials were 10 times more likely to show substantial gains in student learning over time than schools weak on three or more of the five essentials. Additionally, a persistently low score in just one of the five essentials reduced the likelihood of improvement to less than 10 percent. Schools with higher levels of relational trust between teachers and school leaders, among teachers, and between teachers and families tended to have stronger essential supports.

In “So Much Reform, So Little Change,” educational scholar Charles Payne (2008) elaborates on how the common focus on “what works” is misplaced. As Bryk and colleagues suggest, more time should be allotted to understanding the conditions that allow for successful and sustainable implementation in schools. Such implementation is more likely where certain conditions are met. These conditions include elements based on the following list:

Teachers have a sense of efficacy and believe in students and their families.

- Teachers and school leaders have strong buy-in for the reform; as Payne says, “the Big Magic” is “in the thinking and understanding of the people who implement, in the approach they take, in the values they hold dear.” (p. 189)

- Principals are active, engaged, and supportive.

- Schools focus on doing less well and with coherence.

- There is ample time for teacher professional development, common planning, and for teachers to spend with the school leader and coach troubleshooting specific issues.

- A stable team of coaches and consultants are available to support implementation and help school’s problem-solve.

- Schools have several consecutive years to implement the reform; studies of one whole school reform model showed that effects increased substantially after the 5th implementation year.

- Scaling up occurs slowly and cautiously.

In response to these conditions, Payne suggests, “It ain’t the thing that you do, it’s the way you do it,” (p. 190). Thus, we would expect EFA to be implemented and adapted more successfully in schools with stronger levels of the five essential supports. We would also expect for EFA to be more successful if the conditions outlined above are met.

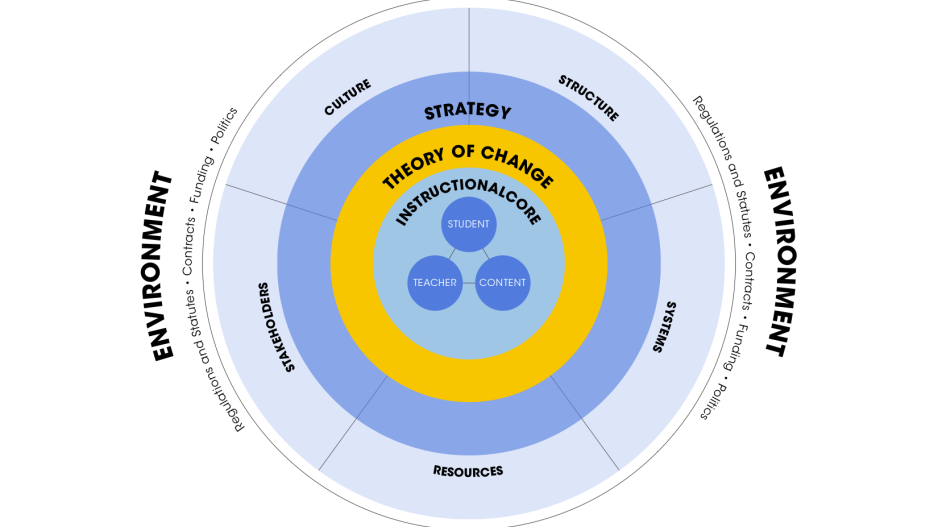

It is also important to recognize that EFA, like many urban district reforms, is situated within a broader district context, and thus implementation will be influenced by this context. The Public Education Leadership Project (PELP) Coherence Framework, derived from interactions with hundreds of U.S. public school leaders, offers a blueprint for district-wide school improvement efforts (Childress, Elmore, Grossman, & King, 2011). As shown in Figure 1, the framework centers the “instructional core,” which consists of teachers’ knowledge and skill, students’ engagement in their own learning, and academically challenging content. According tothe Framework, districts should create a theory of change that articulates a belief about how to improve the instructional core. This theory of change should then inform a high-leverage strategy that enhances all three components of the instructional core and their interaction. Leaders must engage various stakeholders in the development of this strategy and communicate it widely to ensure buy-in and ownership. They must also identify which elements of the strategy schools should adapt and where schools have freedom to adapt the strategy to their unique context. Implementation of strategies is influenced by culture (i.e. norms and behaviors), structure (e.g. departments, taskforces, informal power), systems (e.g. resource allocation, organizational learning, accountability), resources (people, financial resources, technology), and stakeholders (unions, parents, civic and community leaders and organizations, governing bodies). Finally, the influence of environmental elements beyond the district’s control, including regulations and statues, contracts, funding, and politics must always be considered.

It should be noted, however, that dismantling racial opportunity barriers is not a politically innocent endeavor, particularly in a school district with a long and infamous history of racial segregation and racism. Critical Race Theorists argue the permanence of racism and its consequential impacts on the educational opportunities for historically vulnerable students (Bell, 1992; Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller, and Thomas, 1995; Ladson-Billings and Tate, 1995). Milner (2017) argued that inequities become “ingrained and deeply embedded in the policies, practices, procedures, and institutionalized systems of education” (p. 294). Efforts to implement district reforms to dismantle these systems, therefore, need to be intentional.

Specifically, a critical race theory approach to education“involves a commitment to develop schools that acknowledge the multiple strengths of communities of color in order to serve a larger purpose of struggle toward social and racial justice,” (Yosso, 2005, p. 69).

To better understand reform efforts in BPS, we examine academic literature on dismantling racism in urban public schools, barriers to learning opportunities for historically marginalized students, and academic enrichment similar to EFA being implemented across the US and their role in achieving student academic and socioemotional growth.

Dismantling Racism

Achieving educational equity means much more than addressing individual barriers. Educational equity involves systematically dismantling oppressive forces to achieve educational liberation and justice (del Carmen Salazar, 2013; Johnston, D’Andrea Montalbano, & Kirkland, 2017). Achieving educational equity to ensure that all students are world-class learners and best prepared for college or the workforce means having difficult conversations about race and its implications on student outcomes. Research demonstrates that children are most successful in classrooms where they feel valued, and their lived experiences are acknowledged and supported by their educators (Paris & Alim, 2017). However, the history of public education in the United States is one of exclusion and disenfranchisement, particularly for students of color (Yosso et al, 2005; Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995; Paris, 2012).

A legacy of inequity in US public schools perpetuates various disadvantages for marginalized students, including access to academic enrichments, quality school environments, qualified educators, and access to quality school materials/resources (Picower 2009; Yosso et al, 2005; Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995). In fact, research demonstrates that schools that are majority comprised of students of color (90 percent or more) spend $733 less per student per year than schools with 90 percent or more white students (OCR, 2014). Subsequently, Black students are often located in schools with less qualified teachers, teachers with lower salaries, and novice teachers (OCR, 2014). Inequities such as these create unequal learning opportunities and perpetuate beliefs surrounding academic ability for students for color. In fact, students of color are fully capable of learning, but instead experience compounding disadvantage (e.g. poverty, inadequate schooling systems, targeted disciplinary action, etc.) that contributes to differences in academic attainment. Therefore, dismantling school policies and norms that reinforce oppressive educational practices is critical and calls for schooling systems to identify and examine factors that perpetuate racism.

Supporting the academic, social, and emotional well-being of students of color means working to dismantle racism in US public schools. Addressing the systemic inequities that have plagued the US public education system for decades requires hard work and a long-term commitment to serving historically marginalized communities (Paris & Alim, 2017; Ladson-Billings, 2014).

Implementing anti-racist policies as well as culturally relevant and linguistically sustaining practices can aid in shifting mindsets surrounding educating students of color.

Anti-Racist Education

In order to achieve true liberation and justice, schools should move toward becoming anti-racist institutions. Anti-racist education is described as a means to address racism directly (Kendi, 2019; Foster, 2019). Anti-racist teaching confronts prejudice through the discussion of past and present racism, stereotyping and discrimination in society by teaching the economic, structural and historical roots of inequality,” (McGregor, 1993, p. 2). When districts take a stance on being anti-racist, they are prioritizing the needs of students of color, acknowledging that systematic functions pose barriers to their academic achievement. The implementation of anti-racist education through teaching 1) disrupts color-evasiveness and engages in deep conversations about the prevalence of racism and white supremacist practices that impede on the learning of students of color, 2) identifies individual biases of school teachers and leaders as well as acknowledges the impact it can have on teaching policies and practices, and 3) ensures that school curriculum and instruction is culturally relevant and linguistically sustaining, which is detailed in the section below (Foster, 2019).

Through these practices, we distinguish anti-racist education from schools identifying as a multicultural space, as the focus is on the centering the needs of students of color, rather than immersing them into a schooling system that wasn’t built to serve or understand their specific needs (Tator and Henry, 1991; McGregor, 1993). Tator and Henry (1991) argued that anti-racist education differs from multicultural education, as a focus on being multicultural “... ignores the fact that racial differences, and the racial discrimination which flows from [those visible differences] must be challenged by changing the total organizational structures of the institutions.” (p.122). Thus, multicultural education can continue to perpetuate disadvantages for students of color by merely attempting to integrate their experiences into the curriculum rather than addressing the systemic and institutional barriers in place that may impede on the experiences of students of color in educative spaces.

The racial and ethnic mix of U.S. public school students is increasingly diverse, but schooling policies and practices have not evolved to effectively educate these changing demographics. Without educational strategies that acknowledge and incorporate the diverse backgrounds of their students, public school systems will continue to fail to adequately support low-income students of color and eliminate gaps in academic outcomes (Paris & Alim, 2017).

Culturally Relevant and Linguistically Sustaining Education

In order to best serve students of color, Emergent Bilingual students, SWDs, and economically disadvantaged students, school districts should focus on implementing practices that are culturally responsive and linguistically sustaining (Paris & Alim, 2017). Culturally responsive and linguistically sustaining education requires a focus on “sustain[ing] the lifeways of communities who have been and continue to be damaged and erased through schooling,” as longstanding negative perceptions has framed these populations through a deficit framework (Paris & Alim, 2017, p.1). Deficit thinking has not only contributed to oppressive school cultures and climates where the experiences of historically marginalized students are ignored but has also cultivated environments where white-middle class values are viewed as a superior prerequisite to successful educational outcomes.

The implementation of CRLS practices“explicitly calls for schooling to be a site for sustaining—rather than eradicating—the cultural ways of being of communities of color by perpetuat[ing] and foste[ing] linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of schooling for positive social transformation and revitalization,” (Paris & Alim, 2017). Within schools, these practices can be observed as 1) empowering students to share their unique perspectives, 2) incorporating varying learning styles, such as oral stories, to emulate culturally significant practices, 3) being inclusive in classroom materials so students are able to see themselves in the work, and 4) enhancing students’ learning by connecting material realities, and access to institutional power to their lived experiences (Paris, 2012; Paris & Alim, 2017). Culturally relevant and sustaining practices such as these support historically marginalized students by “linking school and culture,” (Ladson-Billings, 1995) to ensure that all students are supported in being academically, socially, and emotionally successful in their schooling. Thus, culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogy exists to further the pursuit for educational justice in an effort to dismantle racist institutions in “the place where the beat drops” (Ladson-Billings, 2014, p. 76).

Public schooling systems cannot be considered equitable until they truly serve the needs of all students. Thus, dismantling racism in schools must be a targeted effort in order for equity to be achieved.In the next section, we will discuss the barriers for students may exist around their race, gender, SES, language, and SWD status.

Barriers to Opportunities

There are many systematic barriers that impede the educative process of students (del Carmen Salazar, 2013; Cherng, 2017; Milner, 2013; Horsford, 2010). As previously highlighted, students of color often experience exclusionary practices that interfere with their classroom learning, peer interactions, and relationships with educators. Emergent bilingual students, SWDs, and economically disadvantaged students also experience oppressive forces within American schooling systems that ostracize and criminalize their existence (Ladson-Billings, 2014; del Carmen Salazar, 2013; Cherng, 2017; Paris & Alim, 2017). In this section, we will discuss specific factors needed to create equitable learning environments, such academic enrichments, resources,and school supports, cultural competency training, and educators of color, as well as discuss how disciplinary practices often criminalize historically marginalized students.

Differential Access to Academic Enrichments, Resources, and School Supports

In many large urban public-school districts, students take high-risk tests to place into academic advancement opportunities (e.g. advanced work courses, best performing district schools, etc.) However, as previously highlighted in this report, there are noted disparities in access to and availability of academic enrichments, resources, and school supports for historically marginalized students, contributing to an observable opportunity barrier. Rather than speaking to the persistent disparity in academic achievement between different student groups, the opportunity barrier highlights the role of race/ ethnicity, socioeconomic status, language proficiency, or other factors on perpetuating inequities (Milner, 2012; Welner & Carter, 2013). This narrative shifts the focus from blaming students for “academic failures” and examines the system that distributes inequitable access to resources and opportunities that promote student success (Milner, 2012; Welner & Carter, 2013).

For example, research outlines that Black students are less likely than white students to have access to enrichment classes, including college-readiness courses and honors placements (OCR, 2014). In fact, the United Negro College Fund (UNCF) (2016), reported that across the US in 2012, only 57% of Black students had access to a full range of math and science classes in comparison to 71% of white students. Additionally, Black and Latinx students are less likely to be in schools offering enrichment opportunities (OCR, 2014), and even when these resources are available, Black and Latinx students are less likely to be placed in honors or advanced placement courses. According to UNCF, Black and Latinx students combined represent only 29% of students enrolled in at least one advanced placement course, even though 38% of the schools these students attend offer AP (ACT & UNCF, 2016).

Ability grouping disproportionately impacts students of color, Emergent Bilinguals, and SWDs. These students are often placed into lower ability courses due to factors such as lower teacher expectations due to students racial/ethnic background, lack of necessary culturally responsive and sustaining engagement skills from educators to build critical relationships with families, and ineffective teaching strategies/lack of culturally responsive and sustaining curriculum and instruction. Until students of color are given the same resources and supports to be successful, barriers to learning will persist, causing differential outcomes in student academic performance.

Lack of Cultural Competency and Educators of Color

Students live complex lives both within and outside of school. Research details the challenge many historically marginalized students experience when matriculating in urban public schools during a period of intensified racist and xenophobic politics and policies (Rogers et all, 2017). At current, many historically marginalized students and their families are immersed in broader societal conflicts surrounding race, immigration, gender and sexual identity. The current environment can generate high levels of anxiety for many Americans, but especially for historically marginalized students and their families.

Hence, implementing culturally responsive and sustaining practices in schools, such as anti-oppressive trainings for teachers is critical (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Flynn, 2015; Lopes- Murphy & Murphy, 2016). Cultural competence trainings in schools should include 1) generating cultural knowledge and understanding about students, 2) stimulating conversations with students and families to best understand how to work in collaboration, 3) checking individual biases about particular groups of students, and 4) calling out racism and other discriminatory practices that systematically target a particular group of students (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Paris, 2012; Cherng, 2017; Morrison et al., 2008). Becoming culturally competent will not happen through the attendance of a singular workshop or professional development day. Rather cultural competency is achieved through the systematic implementation of policies, practices, and behaviors that support a culturally responsive and sustaining learning environment (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Paris, 2012; Howard, 2003).

Diversification of the teaching force by hiring more teachers of color has been proposed as the simplest solution to increase asset-based teaching in schools serving students who have been historically marginalized. Increasing the number of teachers of color could help to mitigate the structural inequities and the lack of cultural understanding amongst teachers (Lewis et al., 2008). This is especially critical as historically marginalized students are now the majority of public-school enrollees (NCES, 2017). For example, students of color have made up a majority of the student body since 2014, students in poverty since 2015, and more than 25% of public-school students are first- or second-generation immigrants, (NCES, 2017). Yet nationally, the teaching force is predominantly white (around 80% according to recent statistics), and New England reflects this national trend. In Massachusetts, students of color made up 38% of all public-school students in the 2018-19 school year (MA DESE, 2019), but only 10% of teachers were people of color (MA DESE, 2019). In Boston, these numbers are 82% and 46% respectively. While the teaching force in Boston is more racially diverse, it still does not fully reflect the student body and poses concern around educator ability to connect with the changing demographics and needs of students and their families.

Boston is a racially and ethnically diverse city. From the perspective of marginalized families, some are entering schools where white people hold positions of authority, namely as teachers and administrators (Vaught, 2008). Recent literature has indicated that the overrepresentation of white educators in urban schools has led to a lack of school-to-home collaboration and cultural understanding between schools and families. Researchers have described the significance of having culturally competent educators and educators of color to build these connections (Jupp & Slattery, 2012; Sleeter, 2017; Ullucci, 2011). For instance, research has highlighted the experiences of some teachers who have spoken about white resistance to and fatigue from learning about race and culture (Crowley & Smith, 2015; Flynn, 2015). Educators who are unable or unwilling to break down cultural barriers to understand the lived experiences of their students and families can cause a significant barrier for student achievement (Paris & Alim, 2017).

Lack of Student Voice

Similar to diversification of the teaching force, incorporating student voice and cultural knowledge into classroom instruction empowers students with direct ownership of their learning experience. However, in most US classrooms, the structure of K-12 schooling is hierarchical (Kohli, 2017).

A typical hierarchical model recognizes people who are in positions of authority and power, such as principals, administrators and teachers, while viewing students and their families as secondary participants (Kohli, 2017). Incorporating student voice into the classroom is a culturally responsive and sustaining practice that allows students to share who they are and what they believe with their fellow peers and educators (Paris, 2012; Ladson-Billings; 1995). Educators can promote student voice in their classrooms through 1) project-based learning, such as capstones, which encourage student-led learning, capacity-building, and critical thinking skills, 2) generating avenues for students to be creative, explore, and develop new ideas which can encourage students to deepen their knowledge and be open to new perspectives, including listening to the voices of students who are typically ignored or seldom heard, and 3) encouraging students to be classroom leaders through activities such as storytelling, which encourages students to share their experiences and passions and can encourage the development of confidence, aid in building connections, and help students understand their voice (Paris, 2012; Ladson-Billings; 1995).

Literature has shown the consequence of stifling student voice on the academic and socioemotional developments of children (Quiroz, 2001). For example, when the aforementioned strategies are implemented into classroom practices, there are observed differences in students’ civic skills (Conner, 2011; Delgado & Staples, 2008, Ginwright & James, 2002; Ginwright, 2010; Rogers et al., 2012; Torres-Fleming et al., 2010), and sociopolitical consciousness (Conner, 2011; Watts et al., 2003) which has long-term implications on their academic success (Perry, Tabb, and Mendenhall, 2015; Conner, 2011). Students who develop a sense of sociopolitical consciousness exhibit an increased resilience to oppressive forces, including the increased ability to critically analyze the relationship between their race, class, or gender (i.e., interlocking structures of oppression) and its impact on their lived experiences both within and outside of school (Perry, Tabb, and Mendenhall, 2015). However, when students lack the opportunity to develop voice and share their cultural knowledge, teachers and administrators maintain all positional power, which can serve as a barrier to student growth and achievement.

Extreme Discipline Practices

All students deserve to learn in environments that are nurturing, supporting, welcoming, and safe. However, school disciplinary practices, such as detention, suspension, and expulsion, pose a barrier to learning, especially for students of color and students with disabilities, who are disproportionally at-risk to experience extreme punishment and zero-tolerance discipline (Morris and Perry, 2016). Zero-tolerance policies disproportionately criminalize historically marginalized students based on the belief that severe disciplinary consequences are required to correct student behavior, regardless of the individual circumstances, (Kirkland et. al, 2019). For example, Black students comprised roughly 16% of the student body in K-12 public schools nationwide, but accounted for 32% of in-school suspensions, 42% of multi-day out-of-school suspensions, and 34% of school expulsions (OCR, 2014). Similarly, the numbers for Latinx students’ suspension and expulsion rates were 22%, 21%, and 22% respectively (OCR, 2014). Examining these numbers by gender, ability status, and SES only reveal more disparate findings. Black girls are suspended at higher rates than girls of any other race or ethnicity (OCR, 2014). Students with disabilities are more than twice as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension than students without disabilities (OCR, 2014). In fact, nearly one out of four Black boys with disabilities (two times the rate of white boys with disabilities) and nearly one in five Black girls with disabilities (three times the rate of white girls with disabilities) faces out-of-school suspension (OCR, 2014).

Morris and Perry (2016) asserted that school-based infractions account for roughly one-fifth of the White-Black opportunity barrier. Students who are continuously and excessively punished for minor offenses or violations in school, are not only having their needs silenced, but are also forced to miss out on quality classroom instruction time (Morris & Perry, 2016). When students are forced to miss out on classroom instruction, their overall school performance is impacted. Missing 3-10 days of classwork due to suspension, for instance, can put a student

extremely behind, with implications on their comprehension of school material, and ability to perform on standardized exams.

Equity Reforms and Student Outcomes

When traditional models of schooling are interrupted by centering race/ racial equity, there are often improved student academic and socioemotional outcomes, such as higher student interest, motivation, and performance, as well as greater confidence and self-perception (Ladson-Billings, 2009; Ladson-Billings, 2010, Irvine, 2002; Gay, 2010; Aronson & Laughter, 2015).

Particularly, we see an increased ability to engage in discourse and strong racial/ethnic identity among students of color in schools where culturally responsive and sustaining education (CRSE) is the focus of reform (Ladson-Billings, 2009; Ladson-Billings, 2010, Irvine, 2002; Gay, 2010; Aronson & Laughter, 2015). In school reform efforts centering cross cultural knowledge, including acknowledging and respecting the importance of individual differences based on students’ identities, languages, and cultures, (Gay, 2002; 2010) emergent bilingual students often have increased multi-lingual development and academic achievement. Similarly, economically disadvantaged students have benefited from school reform efforts focused on being culturally responsive and sustaining to their ways of being, such as their norms and values, learning styles, and backgrounds (Ladson-Billings, 2009, 2010).

Similar to BPS, large urban districts across the country, including NYC, Baltimore, Chicago, Newark, and LA, have begun equity work similar to Excellence for All. For example, a Baltimore City Public Schools (City Schools) taskforce composed of community leaders and district partners proposed an equity policy to the school board in 2019. City Schools subsequently adapted 6 priorities to uphold pillars of excellence around student achievement, effective and efficient operations, and family/community engagement, including:

- Quality curricula and instruction to ensure all students will achieve high standards and annual growth that lead them to graduate prepared to be independent, creative, contributing members of society,

- Quality staff so that all students benefit from transformational leadership at all levels of the organization to ensures the success of district initiatives and sustain a culture of excellence that leads to academic success,

- Climate and facilities so that all students learn in environments that embody a culture and climate of excellence, mutual respect, and safety,

- Parent and community engagement that build resources and opportunities for student success,

- Responsible stewardship and excellent customer service where all students benefit from predictable, reliable, transparent management processes and systems that build internal and external trust and contribute positively to school outcomes, and

- Portfolio of great schools that meet the needs of students and communities. (Excellence and Equity 2020)

The City Schools Excellence and Equity 2020 report outlined the district’s plan to disrupt and dismantle institutional racism in a way that’s focused on honoring the culture, lived experiences, and humanity of students, their families, and the larger community. Through this equity work City Schools aimed to promote student success by ensuring access to high quality academic programing, as well as build equity-based educator capacity.

Similarly, in New Jersey, Newark Public Schools (NPS) recently implemented a Comprehensive Equity Plan with 6 priorities areas to promote student success, including:

- Unified and aligned systems for assessment, data collection, transportation, facilities support, communication, and family and community engagement within an equity culture that values people, diversity, inclusion, and collaboration,

- A rigorous and relevant framework for curriculum and instruction that is inquiry-based, culturally responsive, and student-centered for prekindergarten to grade twelve curricula in all content areas,

-

A strength-based and responsive culture to build strength-based learning and working environments that foster shared beliefs, build relationships, promote partnerships, establish accountability, and value transparency. Culture and climate benchmarks are to be in place to support and celebrate accomplishments, recognize growth, build relationships, respond to needs, learn continuously, and value our differences,

-

Continuous learning for all to develop a unified and well-designed professional learning framework for teachers and school leaders that differentiates learning to their particular needs while providing universal support around shared learning objectives,

-

Integrated system of supports to address students’ social, emotional, and behavioral challenges occurring at all levels, and

-

Strong reciprocal partnerships as student success is a collective endeavor. Partnerships serve a vital role in enveloping every child we serve in a well-designed continuum of support and enrichment that propels them into any future they envision for themselves.(NPS Clarity 2020)

Data for NPS district priorities resulted from deep engagement with various stakeholders across NPS (e.g. school leaders, teachers, and community members). However, this targeted effort is for students in grades Prek-12, whereas EFA focused on grades 4-6. Through these targeted efforts, NPS is aiming to “implement the systems that embrace, celebrate, and empower the diversity among all students and staff” to result in “systemic transformation,” (NPS Clarity 2020). Particularly, NPS is focused on the impact of poverty, racism, immigration and language needs on students’ academic, social, physical, and mental health (NPS Clarity 2020).

As aforementioned research on equity reform described, when schools center the needs of historically marginalized students, including highlighting their voice, lived experiences, assets, and future possibilities, students’ needs, strengths, academic, and socioemotional development are nurtured (Ladson-Billings, 2009, 2010; Gay, 2002, 2010). The above highlighted reforms in Baltimore City and Newark Public Schools align with EFA 5 Pillars of Practice. While outcomes from these equity initiatives are not yet available, based on research that determines success outcomes of equity reforms, (Payne, 2008), we would expect shifts in schooling cultures, conditions, policies, and practices to better support, honor, and uphold students’ cultures, identities, and educational needs.