Key findings presented in this section emerged from our analysis of individual and focus group interviews. Findings are presented thematically in two sections we label as highlights and challenges. The highlights section will present findings demonstrating satisfaction with the EFA initiative. The challenges section will present findings demonstrating dissatisfaction with EFA implementation and BPS structures impacting EFA.

Highlights of EFA

There were at least five highlights: (1) EFA provides opportunities to level the playing field, (2) EFA is designed to challenge ideas about who is “smart” and who is not, (3) EFA can integrate well into school culture, (4) students enjoy EFA, and (5) EFA is designed to provide coaching and support.

EFA Provides Opportunities to Level the Playing Field

EFA was designed to support the academic, social, and emotional development of historically marginalized BPS students. Through this initiative, BPS strived to remove some of the barriers that hinder their academic success. In doing so, EFA provides opportunities to level the playing field. When surveyed, more than 50% of EFA teachers believed that the initiative was accomplishing its original purpose. Specifically, when speaking of the impact of EFA for historically marginalized students, one principal confirmed, for example, “I believe that equity is critical. I believe it is important for all of our students to have the same educational opportunity.”

Prior to EFA, there was “opportunity for some,” in which Black, Latinx, emergent bilinguals, and SWDs were often excluded. School leaders, teachers, coaches, and families all asserted EFA was an initiative to re-distribute resources. One coach described this as:

"I think the purpose was to address this very obvious issue of white kids getting the best of everything...even while they were in communities where they were clearly the minority. Nobody else was getting anything."

Not only was this coach speaking to the antiquated AWC model that existed in many BPS middle schools, tracking students for years based on their performance on a test in the 3rd grade, she was also highlighting the vast enrichment opportunities, programs, resources, and accommodations often provided to families who “can navigate the system.” EFA, however, was an attempt to remove these barriers.

As reported by an EFA principal, EFA schools had less stigma surrounding who deserves to be in “advanced” level class compared to schools offering AWC. The quality of resources the school received improved where, as one principal described, “every school [has] those same types of opportunities... high-quality instruction that’s geared to college prep and getting our kids ready in terms of being 21st Century learners.” No longer was there a belief that one class or group of students was getting all the resources and support. Another principal shared a similar perspective.

"EFA gave the resources of an advanced work program to kids here in our school. But all kids here in our school, not just our highest performing kids, and it doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to me to spend more money on your highest performing kids than on kids who might be struggling or even an average student. So we immediately thought, this is a good program that will match our values as well."

Most principals interviewed could see the difference that EFA was making both in their schools as well as for their students. As such, they described EFA as, “raising standards for the entire class. It is differentiated learning. It is equity-focused.” As supported by study participants, this program reduced opportunity gaps and expanded opportunities for more children. Some school leaders have even reported observing since becoming an EFA school, “a boost in our scores...we had more students of color accepted into exam schools this year.”

School leaders have reported that EFA resources have had major impacts on student achievement. In addition to increased access to exam schools, principals also reported improvement in student performance on MCAS testing. EFA schools with SFL writing support have also reported substantial improvements in student writing and critical thinking.

Secondary data analysis supports the assertion that MCAS scores in ELA improved from 2017-2019 in EFA schools. Table 1 shows ELA achievement categories. ELA scores range from 440 – 560. Overall, ELA scores among Black and Latinx 4th and 5th grade students in EFA schools increased from 2017-2019, from 480.9 to 488.2, although average scores remained in the “partially meeting expectations” category. ELA scores improved for Black and Latinx 4th and 5th grade students in all schools, with the exception of one school with already relatively the greatest average improvement was among 5th grade Latinx students (+9.3), followed by 4th grade Latinx students (+8.9), followed by 4th grade Black students (+7.7), and finally 5th grade Black students (+4.7). Notably, there was improvement among each of these groups.

Teaching staff also supported claims of student improvements through EFA implementation. For example, teacher survey respondents reported slight or substantial improvement in student writing (56%), higher-order thinking skills/ ability to think (59%), students’ ability to work in groups/ collaborate (65%), student’s ability to conduct extensive research (64%), and student’s ability to persevere through multi-step complex assignments, such as capstone and performance assessments (64%).

Additionally, the increase in academic rigor has reportedly improved student retention. One EFA school reported their success in retaining almost every single student. Parents, who might have removed their children due to a lack of academic opportunities, have chosen to keep their children in EFA schools because they are attracted to the enrichment offerings. In addition, some parents are happy to keep their children within a school community where they are comfortable. By leveling the playing field, the identity of EFA schools have reportedly changed. [1] [2]

Some families remarked that EFA schools were a positive place to learn and they were confident that their children were being challenged. Specifically, one school’s atmosphere was reported as “bright and welcoming, with student work, the school’s core values, and notices of events proudly displayed on the walls.” Both parents and teachers have begun to take pride in the EFA community. EFA not only has given students new opportunities, but has provided quality opportunities.

Table 1. MCAS ELA achievement categories

|

Not Meeting Expectations |

Partially Meeting Expectations |

Meeting Expectations |

Exceeding Expectations |

|

440-470 |

470-500 |

500-530 |

530-560 |

EFA Challenges Ideas About Who is “Smart” and Who is not

For many Black, Latinx, emergent bilinguals, and SWDs, EFA has been an opportunity to be challenged academically, socially, and emotionally in ways they never were before. When surveyed, over two-thirds of teachers reported that EFA had a positive impact (slightly, moderately, substantially, or extremely) on their understanding of rigor; 63% reported a positive impact on their willingness to push all students; 63% reported a positive impact on their ability to push all students; and 68% reported a positive impact in their perception of

students’ academic abilities.

In schools with clear racial divides, students of color were often left to feel subordinate to other students. Principals, teachers, and coaches all described the process in which students were formally tracked, leaving many students to question why their schooling experience was different than their peers. School leaders and teachers described the process of “taking a simple test” that determined students’ educational future. One principal of a school formerly offering ACW classes described:

"I had advanced work class here, so some of the issues that would come up would be in third grade we took a test on one day and it decided your fate and tracked you. The vast majority of students who were accepted into the program were white and middle class, so when you would walk through my fourth grade, and fifth grade, and sixth grade classrooms you would see a mostly white homeroom and then you’d go into every other homeroom and it was students of color. Just the impact that sends to people, it sends messages that we’re saying that white people are smarter and white people should have access to this information."

This process created differential access to materials, resources, and opportunities for students to be challenged and pushed academically. Another principal confirmed:

"When you looked at the content and curriculum that was being presented in the rooms, it was totally different. The advanced work classes had books, like novels they were reading, and the general education classes had more of these anthologies where you were reading a portion of the book. So, we were basically then further setting students up for failure ‘cause we weren’t even exposing them to the same topics and ideas."

EFA, however, has removed these barriers to learning. One coach described how EFA has shifted mindsets:

"It’s changing people. Like, I talk[ed] to the principal yesterday...Her school has changed as a school in three years. We meet students who have changed when they take coding or more foreign language. We’ve met teachers who have changed when they’ve read a text or taken a PD or...We’ve seen change in writing. We see change in reading, we see change in speaking...actually change."

Other school leaders confirmed these shifts in student thinking. They asserted, “there is no separation, whether it’s by race or ability.” Some coaches believed this, “makes a huge difference. That to me is a huge, huge benefit.”

Formally, in schools where AWC was offered, some students would generate negative feelings about themselves. This model “caused a lot of divides, mostly around racial lines,” where students and their families felt some “entitlements” around getting into advanced coursework. One case study school reportedly lost one third of their student population a year to schools offering AWC, leaving the remaining students with the dangerous misconception that they were less intelligent than their peers. The effect on students and on school culture was – in the words of school leaders, teachers, and families – “damaging.”

Other schools reported similar occurrences. One principal shared:

"Lots of families would be upset and would leave the school. So, if their child was not accepted into advanced work class, if they had the means to do so they would leave the school. They were choosing not to stay and be a part of the community because they were upset that their children weren’t being segregated. And it’s interesting, because up through third grade they’re all mixed together, and everyone’s happy and everyone loves it... then this test would happen and we’d see a lot of self-esteem issues for kids who thought that they weren’t smart. We actually saw a lot of racial tensions arise between students."

Now, with EFA, school leaders affirmed “kids [don’t] tell me they think they’re dumb anymore because they didn’t get into advanced work class.” Students have been thinking more positively about themselves, their academic abilities, and their future academic successes.

EFA Integrates Well into School Culture

Many principals of EFA schools advocated to bring the initiative to their building. These schools not only wanted a shift in the district culture but to also see all students in their schools achieve success. Many of these principals affirmed, “EFA seamlessly aligned to our instructional focus,” because they were already attempting to do this work.

One principal described, “we were all in on the EFA from the start. As soon as we heard about it, we wanted to do it. Our staff was on board.” Within their schools, principals asserted they were attempting to push policies and practices that encourage learning for historically marginalized student groups. However, through the support of the EFA program, they were able to bring these policies and practices to fruition. School leaders described, through becoming an EFA school:

"We learned more about some of the best practices we were trying to take on that were connected to advanced work classes...some of those things we were already doing like curriculum wise. We already felt like we were using the best curriculum for our students that was meeting their needs. What we really got from EFA on top of like some of the academic things, the addition of foreign language, additional science support, [and] STEM support with a coding and robotics teacher."

Other school leaders agreed that becoming an EFA school allowed them to push their curriculum further, therefore increasing student learning and engagement.

"In full transparency, I don’t think that we would have been able to do the level of work that we’re doing without the resources that EFA has provided for us. They have paid for a whole platform for us to engage in this literacy work where we’re able to use [for the] entire building, not just our sixth grade... we’re using Star reading, another assessment, to do some of the progress monitoring. They’re providing us with professional development where teachers are able to do some research-based investigation to really understand adolescent literacy. So, those are clear opportunities that the entire building is benefiting from."

As a result of these supports, this principal detailed because of their increased instructional focus they are, “making sure that all students are gaining at least a grade and a half by the end of the school year, just because [sic] 93% of our students are not on grade level of proficiency in literacy and reading.” Other principals agreed that EFA was responsible for providing resources to push student learning. One principal noted that EFA enabled the teachers to move quickly through curriculum by not wasting time as they were able to “improve instruction at a rate that would be different without it.”

Teachers surveyed on their instructional practice through the EFA initiative supported these claims. The majority of these teachers believed EFA provided them with the opportunity to more efficiently address grade-level standards (slight improvement 27%; substantial improvement 27%), use student cultural background/ experiences or knowledge to teach content (slight improvement 34%; substantial improvement 26%), address instructional needs of students (slight improvement 31%; substantial improvement 24%), and teach emergent bilingual students (slight improvement 27%; substantial improvement 24%).

Many principals were not only limiting these opportunities to the 4-6th grade classrooms, but rather integrating them throughout the entire school. One principal admitted:

"I don’t just consider our school Excellence for All in those grades that it is Excellence for All. I think our K-5 is Excellence for All, it’s just the way that we teach and it’s the way that our teachers believe in our kids and the work that we put in front of them and the outreach we do and just everything."

There are nuances around EFA integration and implementation. Each of the EFA schools is guided by their own policies, practices, and cultures. Many of the schools range in size and offerings, as well as teacher supports and opportunities for engaging in materials outside of classroom instruction time. Some principals believed, therefore, that school size played a role in how well EFA aligned with their school culture. At one of the smaller case study schools, the principal believed their intimate setting made it easier to tweak activities and regroup from program shortcomings. Parents also believed that the size enabled closer relationships between students and teachers, which supported differentiation, including the ability to have multiple adults in the classroom. In this school, organizational structures, such as the productive use of common planning time, collaboration, and a culture of continuous improvement were in place; in other words, the infrastructure to support the implementation of a major reform. As the principal shared, “When you can breathe a little bit, you can be more thoughtful.” Beyond the school walls, the trust that developed between BPS and the principal also made the principal feel that she could ask for help when she was struggling. In reference to stark opportunity gaps, the principal remarked:

"It’s disgusting. It’s awful. You can’t get paralyzed by it, but you also need to talk about it, with people that you feel like, believe that you want to do the work, and also don’t know what you don’t know. I’ve totally gotten things wrong and then somebody told me and I was like, “Oh, thanks for that.”"

EFA is not just a program to promote equity; it is “a way to run your school.” EFA connects to the core values of many schools by encouraging school leaders, teachers, and families to engage in difficult but necessary conversations about race, power, and privilege.

Students Enjoy EFA

EFA has provided students with quality opportunities to learn. Principals, teachers, and parents reported positive student attitudes and morale

toward the EFA program. School leaders highlighted through participation in the EFA program, “students’ confidence, beliefs, and perseverance has changed.”

No Tracking, No Separating

Prior to EFA, some students could be in the same school and class with their friends since kindergarten and suddenly that would be changed due to the tracking model. One school leader confirmed:

Previously when kids were separated, we saw a lot of friendships end across races. Kids who’d been friends since kindergarten, they work now for the next three years, not in the same room, and it was a mostly white middle-class homeroom, and then homerooms of students with color. We saw like divides and we also, every year in sixth grade needed to have the Office of Equity come in and address the advance homeroom for derogatory statements being used.

With EFA, highlighted across schools and stakeholder groups is that students enjoyed not being separated from their friends. Principals affirmed student feelings, and asserted, “they love the friendship piece... social [and] emotionally, that was good for kids.” Parents confirmed their support of this approach and believed EFA was beneficial for their child’s social and emotional health as well.

Students were also able to support each other academically. Teachers surveys demonstrate that 39% of teachers saw slight improvements in students’ ability to work in groups/ collaborate and 26% saw substantial improvements. Teachers further described that the classroom structure was at times overwhelming, however, students were able to learn from each other. One teacher said:

"I think EFA has for me last year really opened up discussions that happened in my classroom. It wasn’t just the blind leading the blind. You could have six groups of four and there could be at least one or two leaders in each group, and the students would really model behavior."

Teachers were strategic in their instructional style having a large classroom with students on different levels. Allowing students to break into smaller pods where they assisted each other in their learning was a way to ensure that students were supported.

Higher Student Engagement

Teachers, school leaders, and families reported higher student engagement through the EFA program. One teacher said:

"Students really like writing assignments, especially narratives and the research projects; they get really into essays. They see the word essay and they still get scared, but I think the idea of having writing products that are thematically connected to our units but also have a little more student choice to them. I’m seeing a lot more engagement in that this year...writing a bunch of different genres, so I think that has increased the amount of writing students are actually doing in the class."

Across all the case study schools, school leaders and teachers reported students seemed happy with the support structure of EFA. Student satisfaction was particularly high in schools offering SFL writing. Teachers and administrators believed the students improved their writing and became more engaged in their classes and coursework.

In schools offering math support through EDvestors, students have gained more math skills and become more flexible in their thinking and quick problem-solving. Teachers described that formally, students were sometimes discouraged academically and felt overwhelmed. However, through academic, social, and emotional supports provided through EFA, students could now recognize their strengths. Students could debate and engage in appropriate conversations. Students were becoming critical thinkers, learning empathy, and learning how to support one another.

Additionally, the capstone project presented students with an opportunity to engage in project- based learning. Principals, teachers, and parents reported engagement in the capstone project improved student confidence and perseverance in reaching a goal that they have worked towards for an entire year. One principal believed students enjoyed that “it’s very collaborative...they love the autonomy and choice that they have in it.” Teachers also appreciated that it gave them a different way to assess their students’ academic progress beyond testing.

One case study school in particular had large success for the students in the capstone project.The principal described students completed their capstone project on the devastating impact on Puerto Rico of Hurricane Maria. The project afforded students public speaking opportunities, cross-curricular opportunities to connect their learning to the real world, opportunities for Spanish-speaking families to speak to students about their experiences, and for Spanish-speaking students to shine.

Academic Enrichments

The academic enrichment opportunities afforded through EFA encouraged student development. STEM offerings, especially for low-income students and students of color, presented the opportunity for students to be exposed to a field in which they were typically under-represented. Additionally, language components presented opportunities for emergent bilinguals and Spanish speaking families to feel included.

Parents, teachers, and principals all reported students’ excitement about robotics, engineering, and coding classes. One teacher stated, “I mean, the kids are really excited about [robotics]. They get to build something that they’ve never built before.” Teachers reported students would tell peers in younger grades that they could look forward to those activities when they were older - an indicator of students’ enthusiasm for these enrichments. When asked to choose one aspect of EFA that led to positive impact, the top selection was “STEM,” with 33% of teachers attributing STEM to the positive impact of EFA.

Students and their families also appreciated the world language enrichment opportunity. Teachers asserted students, “like the Spanish. I think it validates our Spanish speaking students in a way that makes them feel like they’re the leaders with some language, when that’s sometimes not what they always feel.” Reportedly, these students felt viable and included. They were able to see themselves, their culture, and their identity in the curriculum. In one school, teachers reported Spanish-speaking parents also appreciated that students were running school assemblies in Spanish.

These enrichments, however, were not offered in all EFA schools. As is addressed in the key findings on EFA challenges, not all EFA schools implemented STEM or world language classes due to budgeting, issues with instructors, or optionally selecting other EFA offerings. In order for EFA to be truly equitable, all students engaged in the program should have access to the same quality enrichments.

EFA Provides High-Quality Coaching and Support

The district employed professionals tasked with providing support for EFA schools, including reading, writing, and math curriculum. Through these resources, principals, teachers, and parents, asserted that EFA has improved academics in multiple ways. As formally highlighted, there were reported improvements in student writing, critical thinking, and deep-learning skills.

Interviewees reported positive interactions in schools that were open to working with district coaches and coordinating PD for teachers. In fact, when asked to choose one aspect of EFA that had an impact with EFA satisfaction, 22% of EFA teachers surveyed reported on the positive attribute of ELA/ social studies coaching and 24% reported on the positive attribute of capstone support or coaching. After STEM, these were the second and third top choices, demonstrating nearly 50% of teachers surveyed supported EFA coaching. Although 46% of teacher survey respondents reported that they did not receive any coaching, of the 54% who did receive coaching, 11% reported slight improvement in their classroom instruction, 17% reported moderate improvement, 10% reported substantial improvement, and 5% reported extreme improvement.

One principal outlined how coaching aided in supporting the implementation of EFA in her school:

"No one in EFA ever pressured me to do anything. It was always presented ‘what do you need? What can we do for you? What are some things that are already in place and how can we push the envelope for you? How can we provide more resources and opportunities for your students and staff to engage deeply in this work?’ Early on I found out that there was nothing that EFA wanted from us. Their sole purpose was to support our school community."

Principals and teachers affirmed that coaches operated with a bottom-up approach to strategize with school leaders and teachers on the ways in which they could work together in their schools. Principals would even ask the coaches for help with miscellaneous issues, such as how to find a qualified sub that fit in with their school culture. This coaching, described by participating schools, was “top notch.”

Teachers working with EFA coaches responded positively to the support, especially around PD offerings and instructional support. Teachers affirmed, “I feel like [the coaches] have a better understanding of who we are and our strengths and so we’re better able to work together.” EFA schools enjoyed having coaches who were not judgmental and would work with educators to teach them how to complete tasks, rather than just giving them resources.

One principal described how EFA coaches aided in promoting literacy development:

"A couple of my teachers early on were really interested in working with EFA around literacy interventions. That was something that we were embarking upon and doing a lot of learning as a school community. So, two of the EFA [coaches] immediately took to our literacy project and that work and really began to think about how we leverage their resources to move forward in our work. What supports could they provide as it relates to professional development, our instructional focus, how you’re assessing, how we’re creating a goal and assessing our progress towards that goal and then how this one year planning will impact in the next couple of years."

Other principals described how useful the SFL writing support was, and that “teachers loved it” and “felt it was a useful time.”Through open hours and direct contact, teachers developed “phenomenal, consistent, and individualized” support from EFA coaches.

Many of the EFA schools’ readiness to embrace the coaches and the program aided in these positive feelings. Study participants believed that the coaches were skilled and experienced, but most importantly, that they listened, took time to build relationships, customized supports to the unique needs of each school, and took an asset-based approach. This disposition is critical given a perceived long history of top-down and “one-size-fits-all” reform from Central Office unto schools.

Challenges

Challenges to the implementation of EFA are divided into two sections,

- challenges specific to the EFA initiative and,

- challenges to EFA initiative within the BPS system.

This decision was made to specifically highlight program nuances that are a direct result of EFA operating within a larger system that poses limitations. While EFA is a district initiative, it does not have autonomy to operate independently of BPS. This lack of autonomy poses specific challenges to the implementation of EFA, as the program models enrichments, supports, and recommendations to best prepare historically marginalized students for academic and socioemotional success, but does not have the authority to enforce implementation of these recommendations.

For example, each EFA school has their own academic superintendent who controls the curriculum. These superintendents are assigned from BPS Central Office and are completely separate from EFA. While EFA offers curriculum recommendations and enrichment opportunities, they cannot force schools to make changes to their course offerings. As illustrated in the previous Highlights section, some school leaders do choose to implement recommendations from EFA coaches and staff on ways to improve their course offerings to ensure they’re culturally responsive and supportive of students’ needs, also known as high implementation schools. However, these individual decisions are made by school leaders. The following two sections are broken down as follows:

Challenges Specific to the EFA Initiative

- Communication and collaboration from central office, and

- Limited family engagement.

Challenges to EFA Initiative within the BPS System

- EFA implementation was inconsistent,

- Historically marginalized students continue to be underserved

- Support for Classroom Teachers

Challenges Specific to the EFA Initiative

While EFA has led to many positive impacts, certain challenges impeded implementation across sites.

Communication and Collaboration from Central Office

School leaders’ perspectives varied regarding capacity building and communication between their school and BPS Central Office. Some principals developed stronger relationships with EFA program directors and staff, which they believed contributed to more effective communication around school needs and understanding of Central Office expectations.

Several principals affirmed that they could be honest with the EFA Director and coaches, and that they were flexible enough to listen to the schools’ needs and customize the initiative to their unique school settings.

Other principals resounded in their support for the EFA Director, and the Central Office EFA team, but also acknowledged that there were some challenges. Principals reported that often times it felt they are “working in a silo” when Central Office and school principals should be working together. Specifically, school leaders emphasized that they had specific skill sets that could aid in making critical decisions regarding key aspects of EFA. One principal described:

"I think if there was more collaboration on the offerings and the way that they offer resources so that people on the ground ... As school leaders, there is an expertise that we have, and we most times know what we need, and we know what our colleagues could possibly need based on things that we’ve been really successful at or things where we’ve failed. I think there needs to be more synchronicity around how EFA is planning and what they are offering and how they are presenting."

These mishaps in communication contributed to some school leaders feeling “disorganized,” “frustrated,” and “underserved.” Another principal detailed these feelings:

"And I think, in my experience, it’s when there’s been an unclear expectation, or like, we signed on because we liked the philosophy of [EFA] and it aligns with what we’re doing and we want more resources and then later came ‘this test’ or ‘you need to do...’ some kind of requirements that we didn’t actually sign on to in the beginning and it’s just, some of that, we’re not going to be able to do to the latter. And I’ve expressed it like, ‘if that wasn’t something I signed up for in the beginning, then you can’t hold me accountable for it.’"

EFA school leaders believed in the mission of EFA as a means to de-track and dismantle inequity for students. However, school leaders described an evolving model and expectation for EFA schools to which some principals never agreed. In addition, school leaders also described that sometimes there was conflicting information, which again, left them frazzled by the disorganization:

"What certain structural leaders are asking us to do in different offices, often sometimes conflicts, and there’s no communication between offices. Like, what’s the priority? What are we doing? How are we supporting those schools? But I also think it could be a lot of learning happening between the EFA schools... there’s zero transparency in what the expectation is."

The success of EFA is dependent on school leaders’ effective implementation in their schools. Working together to maintain open channels of communication, so principals are able to express their individual school needs, concerns, and capabilities should be a district priority.

Limited Family Engagement

Families play a key role in the academic, social, and emotional success of their children. However, when asked to describe what EFA was, many families were unable to answer. In fact, many families were unaware that EFA was a targeted district initiative. This was particularly true for families of color and schools serving large populations of students of color.

Clarity Around EFA Offerings

Although there has been a lot of district talk about the EFA initiative, such board and community meetings, many families were still unclear about exactly what EFA was, program offerings, and how their children would benefit. School leaders, coaches, and teachers all believed more work needed to take place around engaging families. One principal said, “I think that part of [engaging families around EFA] is something that we haven’t done at all or well. I don’t think that our families even know that EFA is something different from the work that we’re already doing.”

Several families spoke about their uneasiness with EFA, specifically around their uncertainty of the academic rigor, course offerings, and student supports EFA offers. One parent confirmed, “There’s nothing around the school or anything in the literature that says, ‘We’re an EFA school and here’s what we’re doing.’” Families affirmed that this information could support student success because parents would be more informed on how to support their child’s learning. Specifically, families wished for more information about what students were learning and more ideas about how to engage their children in EFA-like activities, such as critical thinking, at home.

Some parent committees formed to support schools in advocating for a more equity-based schooling model following various reports indicating differential access and achievement gaps among historically marginalized groups. However, this was not the experience of the majority of district families. When asked to speak about this engagement, one parent reported:

"It was a small group of parents that were involved, some of them are here that were involved. I did support but there are parents that are here that were involved in that task force basically but a lot of other parents, the majority, had no idea. Some schools have parent committees that were engaged in the initial district efforts too."

Parents were not only seeking this information to better support their children. Families were also concerned with how EFA was preparing their children for future academic success. Specifically, some white middle-class families with children in EFA schools were concerned whether EFA participation would create a path to exam schools.

Through dismantling AWC in EFA schools, school leaders, teachers, and coaches reported some white families’ belief that they lost a resource to prepare their children for entrance into exam schools. Many of these families openly expressed this sense of loss, reported one

principal:

"If you get the same people, the same White parents who are preaching and mourning about AWC, and exam schools this and [that], on board and you actually invite our parents of color to understand this is an opportunity that was crafted for us but it’s an opportunity that should be for all of us. I think that would gain some momentum and really solidify EFA’s place."

These families reported changes, such as shifts in curriculum offerings (e.g. readings and classroom materials), and amounts of students’ homework when schools transitioned from AWC to EFA. Teachers highlighted that these families have more of a sense of what is lost with EFA rather than what is gained. They affirmed: “Parents don’t really understand what EFA is. I don’t think that people see it as always EFA. I think people see it as we don’t have AWC. They see it more as an absence, than as a presence. It’s about the absence of AWC, rather than the presence of EFA.”

Pushing this initiative forward will require the support of key stakeholders, including the advocacy of parents and community members. All families should be able to engage in these efforts. However, this will require commitment from the district to develop specific strategies for family engagement.

Table 2. EFA Schools Implementation and Fidelity Categorization

|

|

High Implementation |

Medium Implementation |

Low Implementation |

|

High Fidelity |

Mendell |

Harvard-Kent |

|

|

Low Fidelity |

Guild King |

Bates Curley Holmes Gardner Sumner Edwards (MS) Frederick (MS) Irving (MS) |

Edison Grew Orchard Gardens Philbrick |

Challenges to EFA Initiative Within the BPS System

EFA operates within the context of BPS, which limits its capacity and locus of control over schools implementing EFA programming. This section speaks to the particular challenges this posed on implementation fidelity.

EFA Implementation was Inconsistent

EFA implementation was inconsistent, as shown in Table 2. Also see appendix C for EFA coaching support and program offerings by school.

BPS assigned each EFA school to one of six categories, depending on their level of a) fidelity (high or low) and b) implementation (high, medium, or low). High implementation was defined as a) having three or more student programs, including Capstone and either STEM or World Language; b) three or more teacher PD programs; c) leader technical assistance with senior coordinators; and d) a focus on culturally and linguistically sustaining pedagogy (CLSP). Medium implementation was defined as schools implementing a) Capstone; b) at least one EFA enrichment; c) one teacher PD program; and d) limited leader TA. Medium implementing schools may or may not have had a focus on CLSP. Low implementing schools a) did not implement any teacher PD programs with fidelity; b) did not have leader TA by senior coordinators; and c) either did not implement Capstone with fidelity for two or more years or did not have an EFA enrichment.

High fidelity was defined as a) all EFA programs in the school being implemented to fidelity, meaning all teachers were included and 80% of the elements of the program were in place; and b) CLSP being at the forefront of the school’s strategy. Schools were categorized as low fidelity when neither of these conditions were met.

As shown in Table 2, only one school met the criteria of high fidelity and high implementation. One school was categorized as high fidelity, but medium implementation. The other 14 schools were categorized as low fidelity, with two categorized as high implementation, 8 categorized as medium implementation, and 4 categorized as low implementation.

When asked to describe what a successful EFA program should look like, school leaders and teaching staff affirmed, “there are schools that have the EFA model, but they look very different.” They reported varying levels of engagement from outside facilitators of STEM programs, varying components of EFA curriculum and course offerings across school sites, as well as varying levels of coaching within and across school sites. A contributing factor of these inconsistencies was that the curriculum and enrichment offerings for EFA schools was determined by academic superintendents and school leaders, and not EFA program staff. Therefore, variation occurred across sites.

STEM

STEM programs, such as coding, robotics, and engineering, were not offered equally across school sites. This inconsistency is reflected in the teacher survey data, where 16% of teachers responded that they were not at all satisfied with STEM programs and 26% expressing that they were very satisfied. Principals were given autonomy to determine what EFA offerings they believed would be a good fit for their school setting. One principal affirmed:

"We do not have STEM at this school. I just did not feel like it was a tight enough opportunity for us. Having worked with college interns in the past and people who are not dedicated to one specific building, I just saw a lot of gray area there. So, I decided that we would not move forward in that regard."

Within this school, this principal predicted the unreliableness of educators who are mobile throughout the district and transient within their position. She made a positioned choice to not include this component of EFA for her students. While she noted other aspects of their EFA curriculum were thriving, students within this site weren’t exposed to a key component of the EFA pillar structure.

School leaders and teaching staff believed that STEM enrichments would aid in creating “world class learners,” but schools that agreed to STEM offerings also experienced challenges. Teachers reported inconsistencies across sites, and asserted, “a successful EFA school is a school that has the resources to educate every student... has enrichment opportunities that are highly engaging... computer skills... robotics... STEM.” However, teachers across case study sites reported many instances in which working with STEM instructors was frustrating because

they would be late or no-shows, causing disruptions in student and teacher schedules. One principal affirmed the biggest challenge in their school was the STEM component, but was hopeful for improvements in year two. Other principals added, “the STEM...they’re [teachers and students] super frustrated ‘cause people don’t come.” Another school reported an entire school year of no robotics teacher, even though it was built into their course offerings.

EFA staff were responsible for the hiring of STEM instructors. Therefore, inconsistencies in instruction received is both a BPS systematic issue and a challenge within the EFA program. However, the need to hire transient workers is the result of EFA operating within the larger system of BPS.

Inconsistent EFA Models Across and Within School Sites

Some teachers noted that inconsistent models of EFA within and across school sites made it challenging to identify what EFA as an equity-based initiative should look like. For example, within one school, each grade level could be implementing EFA differently, such as “teacher planning meetings to share curriculum plans” organized by teachers in one grade but not another. Then, as previously discussed, across school sites, some students may have STEM enrichments like robotics and coding, or world language classes like Spanish, and other schools have nothing, or limited resources. Teacher interviewees explained:

"There were inconsistencies with what EFA looked like. So, we’re talking about how it would be nice to know what excellence probably looks like among schools but even within schools, there was a lot done, individual teams, grade level teams to create what they thought it might look like all the different components, like what does the budget look like? And again, in a school where you have a Spanish teacher for 30 kids versus 120, it’s a little different."

Teachers across school sites described frustration with the lack of consideration for the varying needs of schools based on their size, student population, and instructional model. EFA implementation was even a challenge within schools, as some grades worked as a team model and others did not. When asked how lack of fidelity reduced the functionality of EFA, one teacher reported, “it feels like a bunch of us kind of struggling. It doesn’t feel thoughtful and it doesn’t feel responsive towards our students.”

Coaching

Even though coaching was a required component of EFA, some principals exercised autonomy in the level of engagement coaches would have in supporting their school. Senior coaches were made available to assist each EFA school in year two of program implementation, as previously highlighted. At this point, some school leaders were more open to the idea of coaching than others. For teachers, this meant limited support around SFL writing, resources to engage students in deep learning, and support in crafting instructional models. For instance, of the teachers surveyed, 35% reported never interacting with ELA, social studies, language, or reading coaches and 33% reported interacting with coaches only 1-5 times during the school year. 59% reported never interacting with writing coaches and 15% reported interacting with them only 1-5 times.

One reason school leaders described they decided to limit coaching was due to teachers’ other PD responsibilities. One school leader described, “my people were willing to do it. But it was a lot. Like a lot of work to teach full time and do that.”

Coaches also described their experience in attempting to engage schools that actively wanted to limit coaching. They asserted:

"There are some schools where you might wander the halls because it was so disorganized...You give [principals] a report on the need’s assessment, they don’t even give [teachers] that... And what about if you do a big professional development in the full staff, it doesn’t translate into practice and there’s not a whole lot of support by the leadership. You know that you’re not going to gain a lot of traction from that school. So, bring it back to the team, [and] see if we’re going to continue throwing away our time at this school."

Coaching was also limited by capacity, and decisions were sometimes made to place coaches in schools where they could be most effective. At one school in particular, the principal confirmed, “My literacy coach was taken back. I have had two meetings now with [a coach and BPS EFA Director] about what coaching could look like here next year.” Central Office confirmed that in these cases, coaching is allocated based on need, and a schools’ continued openness and support of on-going coaching.

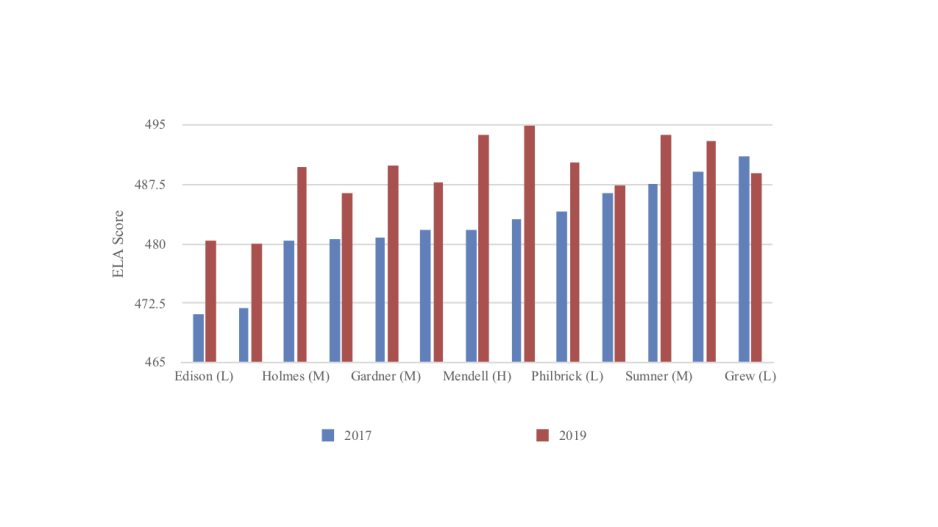

Together, these findings summarized in this section demonstrate inconsistency in the implementation of EFA within and across schools. To what extent did this inconsistency in implementation influence achievement? Using secondary data, we explored the relationship between fidelity and change in ELA scores from 2017-10. Table 3 shows the average change from 2017-19 for Black and Latinx 4th and 5th grade students, in order from the largest to the smallest change. Figure 2 shows ELA scores among 4th and 5th grade Black and Latinx students in 2017, compared to 2019, in order from lowest to highest 2017 scores. For simplicity, the table and figure categorize schools into three groups based on their implementation and fidelity. All schools with either high implementation and/or high fidelity are categorized as “high” (N=4). Schools with low fidelity but medium implementation are categorized as “medium” (N=5). Schools with low fidelity and low implementation are categorized as “low” (N=4).

Table 3. Average ELA Change from 2017-19 for Black and Latinx 4th and 5th Students

|

School |

Implementation/ fidelity level |

ELA score change (points) |

|

Harvard-Kent |

High |

12.7 |

|

Mendell |

High |

12 |

|

Edison |

Low |

9.4 |

|

Holmes |

Medium |

9.4 |

|

Gardner |

Medium |

9 |

|

OG |

Low |

8.2 |

|

King |

High |

6.1 |

|

Sumner |

Medium |

6.1 |

|

Philbrick |

Low |

6.1 |

|

Curley |

Medium |

5.8 |

|

Bates |

Medium |

4 |

|

Guild |

High |

1.1 |

|

Grew |

Low |

-2.2 |

Table 3 shows that the only two schools that were categorized as high fidelity also had the largest ELA score change among Black and Latinx 4th and 5th grade students. Figure 2 shows that these schools had lower 2017 scores than five of the other schools but the highest scores in 2019. The fact that ELA scores rose the most in the two high fidelity EFA schools indicates that EFA implementation might have supported ELA improvement; however, it is also possible that these schools were on track to improve anyway and the same qualities that drove improvement also supported successful EFA implementation. Our qualitative data suggests that both of these possibilities could be true.

Aside from the clear association between the two high fidelity schools and ELA improvement, there is no discernible pattern between implementation categorization and ELA score change. For example, two of the “low” schools were among the schools with the largest positive gains. It’s important to note that these schools also had the lowest 2017 scores so there was more room for positive growth. Additionally, one of the schools categorized as high implementation had the smallest positive gain, although it should be noted that 2017 scores at this school were relatively high compared to most other EFA schools.

|

|

4th grade - Black students |

5th grade - Black students |

4th grade - Hispanic students |

5th grade - Hispanic students |

|||||||||

|

School |

Implementation level |

2017 score |

2019 score |

Change |

2017 score |

2019 score |

Change |

2017 score |

2019 score |

Change |

2017 score |

2019 score |

Change |

|

Mendell |

High |

477.6 |

497.7 |

20.1 |

477 |

490.9 |

13.9 |

488 |

498.8 |

10.8 |

482 |

488.7 |

6.7 |

|

Guild |

High |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

488.2 |

488.3 |

0.1 |

483.2 |

486.2 |

3 |

|

Harvard-Kent |

High |

478.9 |

498.4 |

19.5 |

480.9 |

494.1 |

13.2 |

484.3 |

495 |

10.7 |

485.1 |

495.9 |

10.8 |

|

King |

High |

484.9 |

489.8 |

4.9 |

480 |

485.7 |

5.7 |

485.9 |

489.5 |

3.6 |

473.7 |

484.5 |

10.8 |

|

Curley |

Medium |

487.8 |

475.5 |

-12.3 |

477.1 |

482.3 |

5.2 |

474.1 |

487 |

12.9 |

486.5 |

492 |

5.5 |

|

Bates |

Medium |

487 |

492.8 |

5.8 |

494.3 |

492.6 |

-1.7 |

488.6 |

485.1 |

-3.5 |

488.7 |

499 |

10.3 |

|

Gardner |

Medium |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

482.7 |

485.7 |

3 |

479.3 |

495.8 |

16.5 |

|

Holmes |

Medium |

480.5 |

486.5 |

6 |

476.8 |

492.8 |

16 |

488.6 |

490.3 |

1.7 |

478.8 |

491.8 |

13 |

|

Sumner |

Medium |

483.8 |

492.1 |

8.3 |

489.7 |

493 |

3.3 |

488.5 |

492.5 |

4 |

488.2 |

496.2 |

8 |

|

Edison |

Low |

464.4 |

469.9 |

5.5 |

466.5 |

479.8 |

13.3 |

471.6 |

482.4 |

10.8 |

474.4 |

485.7 |

11.3 |

|

Grew |

Low |

487.8 |

487.8 |

0 |

486.5 |

485.1 |

-1.4 |

491.1 |

491 |

-0.1 |

504.1 |

493 |

-11.1 |

|

OG |

Low |

465.7 |

478.4 |

12.7 |

470.4 |

467.5 |

-2.9 |

470.6 |

485.7 |

15.1 |

481.3 |

490.1 |

8.8 |

|

Philbrick |

Low |

482.2 |

495.7 |

13.5 |

489.5 |

475 |

-14.5 |

478.8 |

499.6 |

20.8 |

483.6 |

474.8 |

-8.8 |

|

Average (weighted) |

|

479.7059 |

486.4 |

7.7 |

478.7 |

483.5 |

4.7 |

480.4 |

489.3 |

8.9 |

483.1 |

492.4 |

9.3 |

Next, we examined ELA changes from 2017 to 2019 for each group – 4th grade Black students, 5th grade Black students, 4th grade Latinx students, and 5th grade Latinx students.

As shown in Table 4, there was some evidence of a relationship between implementation and the consistency of ELA achievement gains across sub-group:

- 4 off 4 (all) high implementing schools improved for every sub-group.

- 2 of 5 medium implementing schools improved for every sub-group.

- 1 of 4 low implementing school improved for every sub-group.

The relationship between implementation and growth was most evident for Black students. The two schools with high fidelity had the largest gains for 4th grade Black students, and one of the high-fidelity schools had the largest gains for 5th grade Black students. However, for Latinx 4th grade students, the largest gains were in two of the low fidelity/low implementing schools, and for 5th grade Latinx students, the largest gains were in two of the low fidelity/ medium implementing schools. This suggests that EFA may have been more impactful in regard to ELA scores for Black students, compared to Latinx students.

Historically Marginalized Students Continue to be Underserved in EFA Schools

Historically marginalized students are still being underserved in EFA. Student performance data shows improvements in some EFA schools. However, gaps persist around race. Shifting district mindsets is essential to ensure the successful implementation of EFA. The program itself, as described by one school teacher, “is not a magic bullet,” to address district-wide systematic issues. One teacher argued, “We are not servicing our children of color. We are not servicing our English language learners and this is not a third world country. This is Boston for God’s sakes.”

Engagement of Families of Color

Many of the families of EFA students have varying cultural experiences and expectations around in-school engagement. Whether families have home or work responsibilities, or different perspectives on what school engagement should look like, there should be targeted efforts to reach these families.

A teacher for one case study site described a clear indication of a cultural divide within their larger community. School leaders reported that some families, mainly families of color who recently arrived in the U.S., did not understand that education in the U.S. was compulsory, and there were no on-boarding policies or practices in place to aid families in supporting their child’s learning. This individual school is making more of an effort to increase family engagement, including new initiatives involving translation services, childcare, changing the location of activities, and providing food.

Some EFA teachers believed BPS educators should be more reflective of the larger BPS community, and stated in an ideal world, EFA would “look like the community it serves.” One EFA school, for example, has 70% emergent bilingual students but mostly white teachers. While some of these teachers speak Spanish, they don’t always have the cultural competence to engage with families from different ethnic backgrounds.

In a school that is working to dismantle inequity,cultural competency is critical. Coaches have begun to speak with some school leaders and teachers about cultural competence, including how to work with students of color. However, schools have to be receptive to coaching and support, as well as acknowledge this is an issue for students and their families. These findings demonstrate that better strategies are needed to engage historically marginalized families. Parents, as their child’s primary caregiver, are best prepared to speak on the needs of their children. Optimal student achievement occurs when schools and families work together to promote success.

Centering White Families

Certain policies, practices, and cultural norms within BPS continue to privilege the educational trajectory of white students. Many white families often reported “they take a gamble” when deciding to enroll their children in the Boston public school system. This “gamble” as they described, means only investing in the public-school system if their children are positioned to achieve what they deem the best schooling options (i.e. selective enrollment schools, AWC coursework, and exam school acceptance). One parent described:

"For most White people in [neighborhood], if you take the ... This is the gamble that we took. We’re a white family. We have two sons. We’re going to stay in Boston. We’re going to do this. Our kids are going to go to an exam school. Oldest child got into advanced work, youngest... well, he didn’t get in. We lost the gamble. That’s the end game and we lost. It was a terrible six months until we figured out what to do... We’re sending him to private school."

Other parents argued that families even “petitioned to get their children enrolled in AWC classes” if they were not originally accepted.

A system that does not privilege the educational experiences of marginalized students will never be equitable. In fact, many participants highlighted the need to completely re-haul the education system in BPS, and offered recommendations to do so. School leaders and staff highlighted the urgent need to center Black, Latinx, emergent bilinguals, low SES and SWDs through continued PD and curricular expansion, including culturally responsive instruction and trainings for educators as well as academic enrichment opportunities that are accessible for all students.

Some principals argued that this can happen by taking EFA full scale across all 84 schools serving 4th-6th grade students:

"I think EFA needs to be full scale across the district. I think that the office needs to be recognized for the work that they’re striving to do to support the closing of the opportunity and achievement gap. They need to be able to be at the table to inform how do we all have high expectations for all of our students, especially our students of color, and what techniques and strategies do we need to rethink what’s in place and to really change our mindsets as educators because we’re racists and there’s no equity here in Boston. It’s the worst."

Teachers agreed with this point, and asserted that EFA and AWC cannot both operate in the district if the goal is to truly be equitable:

"You know we have all the white kids in AWC and all of our students of color and students of second-language learners in other classrooms... very divisive. So, my understanding was that EFA was BPS’s answer to that actual problem and we were shown studies...we are Excellence for All which in fact is a better model in theory than AWC but the district refuses to let go of the divisive model. And I think it sends a message to parents, they’ve never clearly stood behind EFA in a way that makes it strong and viable."

Other BPS support staff argued that the divisive system in place that privileges the academic achievement of White students over students of color is working as intended:

"There’s this idea that the system that exists is broken. It’s not broken. The system that exists is working the way it’s designed to work. So, it’s actually working quite fine. So, there’s this narrative that we have to fix the system and that’s not really what the real change is. The real change work is in dismantling the EFA system and developing it and doing something else."

Other district staff supported this idea. While acknowledging the education system was working as intended, and employing an antiquated model under-serving the most vulnerable students, many struggled with what an ideal system should be or look like:

"So, we [EFA] talk about fixing systems. We’re not fixing the system. We need a different system. I don’t know what that system looks like. I don’t know what that system is. I don’t know how to build that system. I don’t even know... I just don’t [know] what that is, I know it’s not this."

For these district staff, an initiative like EFA can only be truly effective when the entire system is dismantled, and rebuilt to de-center white families.

Meeting Needs of Students of Color

Some school leaders are struggling to prioritize conversations about race within their schools. Although one principal reported looking to the Central Office for support with these conversations, she described the difficulty of having conversations about race and power with teachers who were “swimming in management issues.” This finding demonstrated the needs of historically marginalized students were not always a high priority for school leaders managing many responsibilities.

When teachers discussed how underserved students are impacted when not prioritized, they described:

"They’re actually getting the crumbs. They’re not even at the table. They’re not even thought of in policy and with the curriculum in any way, any form of academia. I’m not sure to talk about humanity that doesn’t even exist. So, these teachers come out of college and you know they’re, ‘Oh, I’m going to save the masses.’ They go hoping, I’m going to save the masses. And when they get confronted with the masses, now they don’t know what to do. They are scared of the children."

Some coaches struggled with existing within this system knowing that it’s inherently racist. One coach described:

"[EFA] becomes a lot more complicated where I don’t really know what it is right now. If you were to ask me because everything that it’s supposed to be, [EFA is] still inherently white supremacist and racist. So, are we combating the system? Are we disrupting the system?"

School leaders agreed that the success of students of color required “rethink[ing] how we provide students with high-quality education overall, with only having pockets of high expectation,opportunity, and rigor.” Students should feel they are valued and their experiences represented. To do this, difficult conversations need to take place in order to shift district mindsets around race.

Language Barriers to Learning

Some teachers affirmed that outside course facilitators were not always prepared to engage with a wide range of learners. For example, one team of STEM coaches were assigned a group of emergent bilingual students without any PD on how to engage students with varying levels of English-language proficiency. This teacher stated, “last year, when the robotics instructors first showed up, they were really surprised that they were teaching a class full of students who basically didn’t speak English.” Having this knowledge while developing their curriculum would ensure educators make necessary accommodations to adequately address student needs, especially assumptions about “students’ English proficiency.”

Other teachers agreed that there should be more supports to prepare educators to meet student needs:

"From day one, instructional planning should be focused on students who have higher needs. [Ensuring] that there’s adequate support for students who have special needs, for English language learners. That’s just not all, all classroom teachers ... There has to be a systematic approach in the instruction of all students...We [should] have really clear responses and steps when a student isn’t meeting expected growth."

Teachers, coaches, and other school staff were aware that students bring unique experiences into the classroom. These experiences influence the ways in which they learn and engage. Curriculum and instruction should be reflective of those experiences, and targeted to meet the specific needs of students, particularly those being underserved.

Teachers confirmed:

"We have to stop and say, ‘What we’re doing is not working. We’re just further marginalizing them.’ They don’t have all of the same benefits sometimes at home, that other kids have. So, there have to be things that we’re doing at school to make sure that those kids get the extras that they need. We’re never gonna close an achievement gap...The kids who already have it, are gonna be even further ahead.”

EFA alone is not going to erase the systemic barriers via policies and cultural practices that impede the learning of historically underserved BPS students. There needs to be intentional acts to disrupt mindsets if real progress is going to be made to meet the needs of students, especially for Black, Latinx, low SES, SWD, and emergent bilingual students.

Support for Classroom Teachers

EFA teachers reported feeling overburdened by classroom sizes, lack of teaching supports, and the inability to fully meet student needs in a large classroom with a range of learners. When asked what could aid in increasing the success of EFA, teachers collectively reported, “more bodies in the classroom.”

One teacher described the daily challenge of managing their classroom without additional teaching assistance:

"I would say more teachers, more bodies to help a variety of learners to even the playing field for all students. But you can’t do that when you have students who are significantly below grade level with students who are significantly above grade level...I feel like a disservice to the students...because as teachers you have to decide who am I going to help today?"

Another teacher described her experience with limited classroom support when working with students with direct needs:

"So, last year, I had two students who didn’t speak any English. My ESL support was taken away by a special education class, where that was inclusion, and higher needs. So, well, I’m doing the engaging your curriculum, I had two kids who couldn’t read. So, working with them, huge behavior problems. It was really hard. There was no...it would be great if EFA looked at the classroom."

Teachers described how limited classroom support was a challenge to achieve equity in the program. They described an equality versus equity framework, where everyone is given the same materials versus students given resources to address their individual needs:

"But, equity is where you give different people what they needed in order to access what they’re trying to access. And, when we have kids, who are reading at a 2nd grade level, or kids who don’t know add one plus two without counting on their fingers. And, can’t do more than single digits, even with fingers. Then, if we’re expecting them to access whatever we’re doing, whether it’s ratios or algebra, whatever’s happening in class, they just can’t. They just sit there, or they’ll try and find ways to get around it, because they’re just so lost."

Teachers often reported feeling exhausted in their position in an attempt to serve all students’ needs to the best of their ability. One teacher stated this contributed to teacher turnover:

"Students need extra help, and there is only one body in a classroom of 26...I don’t have enough training, I don’t have enough things to help me do what I need to do. So, that’s like another reason there’s turnover. There’s no consistency."

Principals also acknowledged that limited classroom support was a challenge. They affirmed teachers’ feelings of needing additional classroom support and stated teachers “believe in not tracking the students.” However, the limitations in classroom support result in teachers “zero[ing] in on who really needs to grow,” leaving some students not getting the attention and support they need. One principal added:

"I think that teachers would say they would love to have an additional level of support to meet the range of learners and to be really thoughtful about when you have a range of A to Z in your space and 25 kids, how they sometimes feel like they maybe aren’t getting to everyone."

Increasing teaching support in the classroom would help educators to reach a wider range of students. As it stands, teachers believe a lot of students are not being served in a way that contributes to their continued growth and learning. If achieving equity is the goal through EFA, then supports need to be provided to ensure teachers are able to reach a range of learners. EFA staff do not currently have control over ensuring teachers have this kind of support.