by Tyler Whittenberg & Maria Fernandez

Advancement Project

Context

School policing is inextricably linked to this country’s long history of oppressing and criminalizing Black and Brown people and represents a belief that people of color need to be controlled and intimidated. Historically, school police have acted as agents of the state to suppress student organizing and movement building, and to maintain the status quo. Local, state and federal government agencies, designed to protect dominant White power institutions, made the intentional decision to police schools in order to exercise control of growing power in Black and Brown social movements. In this, the police have been remarkably successful: despite the over 60 years that have passed since schools were integrated, Black and Brown students are denied the opportunity to fully participate in and benefit from public education.

The introduction of police to school districts serving Black and Latino students set the stage for today’s school policing infrastructure. Law enforcement was embedded in schools beginning as early as the 1940s. Indianapolis Public Schools hired a “special investigator” to serve the school district from 1939 to 1952, when the position was renamed “supervisor of special watchmen.” ¹ In 1970, the watchmen would become the Indianapolis Public School Police. ² Similarly, the Los Angeles School Police Department traces its origins to 1948, when a security unit was created to patrol schools under the pretense of protectin school property after integration. ³ For more information on the history of school policing, read We Came to Learn: A Call for Police-Free Schools.

Evidence

Black students are pushed out of school, arrested, and funneled into the justice system at alarmingly disproportionate rates, despite research confirming that Black students do not misbehave at higher rates than their white peers. 4 Although Black students represented only 15% of the national student population during the 2015-2016 school year, they were 31% of the students arrested or referred to law enforcement. 5 This is not surprising, considering that police officers have been found to misperceive Black boys as older and view them as less childlike and less innocent than white boys of the same age suspected of committing the same crimes. 6 The experience for Black girls in schools is even worse. When compared to white girl students during the 2015/16 school year, Black girls were four times more likely to be arrested, three times more likely to be referred to law enforcement, and two times more likely to be physically restrained. 7

After being arrested by school police officers, students face a myriad of collateral consequences that harm their future, their families, and their communities, including: loss of instructional time and course credits; legal costs and court fees; separation from family; emotional and physical trauma; challenges to their immigration status; loss of housing assistance; and loss of employment. 8 For some students, this means that a minor schoolyard scuffle could ultimately result in their family being evicted from public housing or the deportation of their parents. These consequences only exacerbate racial and ethnic disparities already entrenched in a justice system where Black youth are five times as likely to be incarcerated as their white peers. 9

Additionally, placing police officers in schools puts students at risk of physical harm. The Alliance for Educational Justice has documented 106 cases of school police officers physically harming students of color by using unnecessary force when responding to typical schoolyard behavior. ¹0 For immigrant students, police presence also increases the risk of deportation for themselves and their family members.

After mass school shootings, like those occurring at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012 and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018, policymakers have responded by calling for more police officers, surveillance, and guns in schools. ¹¹ Research and the experiences of countless students, educators, and families have taught us that while these proposals may create the appearance of safety, the actual effects wreak havoc on school climate and fuel the school-to-prison pipeline. The over-policed atmosphere can initiate, rather than mitigate, misbehavior by increasing anxiety, alienating students, creating a sense of mistrust between peers, and forming adversarial relationships with school officials. ¹² Instead of ensuring safety and improving behavior, police presence often heightens disorder among students by diminishing the authority of school staff. ¹³ When students perceive a negative school climate, they are less likely to be engaged, more likely to be truant or dropout and more likely to have issues with bullying. ¹4

Students, especially students of color, regularly interact with metal detectors, school resource officers, handcuffs, sweeps, and drug sniffing dogs as part of their school day. The presence of police in schools also conditions students of color to accept the constant presence of police as a part of their everyday existence. Placing officers in schools makes them agents of socialization, teaching impressionable Black and Brown children that compliance is of utmost importance. ¹5

There is no evidence to demonstrate that increasing law enforcement, surveillance, and guns in schools makes students safer. Conversely, the increased presence of police officers in schools has been linked to increases in school-based arrests for minor behaviors and negative impacts on school climate. ¹6 Thus, rather than make schools safer, the presence of law enforcement in schools places students of color at risk of criminalization for age-appropriate schoolyard behavior.

Effective strategies

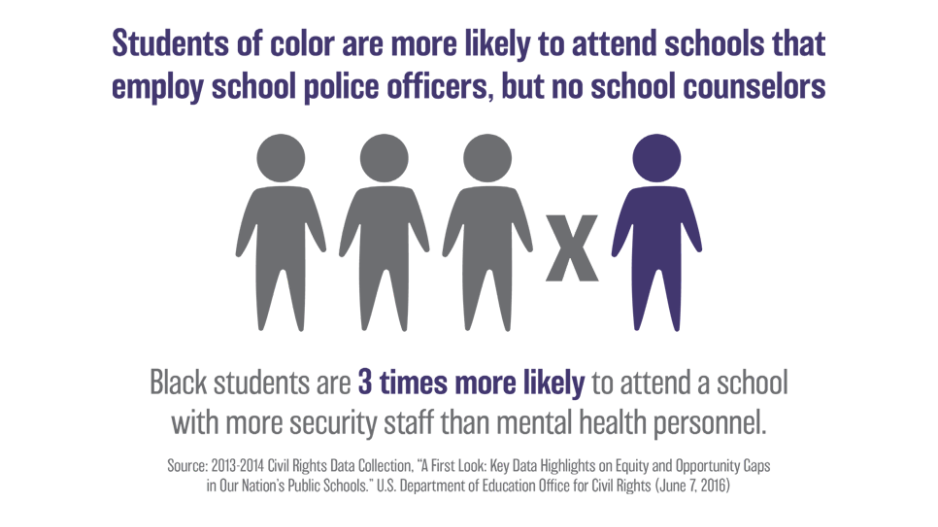

There are obvious, less discriminatory and less punitive methods of addressing school safety than policing and surveillance. Safety is found in schools that have positive school climates and support students’ needs through guidance counselors, social workers, health care professionals and others who are trained to identify and address concerns without criminalization. One of the most effective methods to improve school climate are to engage students and educators in pro-social activities that build positive relationships and instill a sense of community throughout campus. ¹7 School-wide restorative justice initiatives are effective at making schools safer by improving school climate and promoting emotional, social and communication skills that follow youth into adulthood. ¹8 Yet these methods do not receive comparable or adequate funding – ultimately undermining the objective of keeping students safe.

Students are safer when policymakers invest in trained restorative justice practitioners, behavior interventionists and counselors to help prevent and address safety concerns, ensure a welcoming environment and meet students’ needs. Every dollar spent on police, metal detectors, and surveillance cameras is a dollar that could instead be invested in trained professionals that support, not criminalize children.

To ensure that all students attend schools that are safe and nurturing, policymakers should end school policing programs and invest in supports that are proven to improve school climate, teach social- emotional skills and provide students with resources and services. To achieve this end, we recommend that policymakers:

Divest in school policing and student surveillance

Invest in measures that are proven to improve school climate, like fully-staffed, school-wide restorative justice initiatives and positive behavior interventions and supports.

Decriminalize student behavior

Eliminate laws and statutes that criminalize students for age- appropriate behavior, like the statutes that make it a crime to disturb school or act in an obnoxious manner in school. Eliminating these laws while enacting policies that require the use of alternatives to exclusionary discipline and arrest will decrease the number of youth funneled into the school-to- prison pipeline and help establish a positive school climate for all students.

Deprioritize the use of law enforcement in schools

Ensure that police officers are only called into schools as an instrument of last resort. This can be achieved through policies and interagency agreements that eliminate the regular presence of police officers on campus and place limits on requests for police assistance. It is also necessary to independently review instances when educators and administrators call police into schools to ensure these policies are being followed.

Demilitarize schools, and disarm school personnel

Enact policies that remove metal detectors, various forms of student surveillance and police officers from schools. Additionally, policymakers should prohibit police officers and school staff from carrying weapons on school campuses, including electronic restraints, chemical restraints. Armed school personnel and police place students at risk of abusive force and are harmful to the overall school climate.

Develop “Sanctuary School” models

where all Latinx, Black, and Indigenous students feel free to learn and are safe from the threat of school- based arrests and targeting by school police officers and ICE agents. Policymakers should also prohibit undue information sharing between law enforcement, ICE and school personnel as well as prohibit all immigration enforcement on school grounds.

Related Research

- We Came to Learn: A Call for Police-Free Schools

- Cops and No Counselors

- 11 Million Days Lost from School article

- Reaching a Critical Juncture for Our Kids: The Need to Reassess School-Justice Practices

Examples of Best Policy/Practice

- Advancement Project national office Alliance for Educational Justice Dignity in Schools Campaign

- Center for Popular Democracy Girls for Gender Equity

Multimedia

Author

Tyler Whittenberg, Deputy Director, Ending the Schoolhouse to Jailhouse Track Project Advancement Project

Maria Fernandez, Senior Campaign Strategy Associate Advancement Project

Footnotes

- Brown, B. (2006). “Understanding and Assessing School Police Officers: A Conceptual and Methodological Comment.” Journal of Criminal Justice, 34, University of Texas at Brownsville.

- Ibid

- French-Marcelin, M. & Hinger, S. (2017). “Bullies in Blue: The Origins and Consequences of School Policing.” American Civil Liberties Union.

- Skiba, R. (2013). Reaching a Critical Juncture for Our Kids: The Need to Reassess School-Justice Practices. The Association of Family and Conciliation Courts.

- U.S. Department of Education for Civil Rights. (2018). “2015-2016 Civil Rights Data Collection, School Climate & Safety”

- Goff, P.A., Jackson, et.al. (2014). “The Essence of Innocence: Consequences of Dehumanizing Black Children,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2018). “2015-2016 Civil Rights Data Collection, School Climate & Safety”.

- Burrell, S. & Rourke, S. (2011). “Collateral Consequences of Juvenile Delinquency Proceedings in California: A Handbook for Professionals.” Pacific Juvenile Defender Center.

- Sickmund, M., Sladky, T.J., Kang, W., & Puzzanchera, C. (2015). “Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement”.

- Advancement Project National Office. (2018). We Came to Learn: A Call for Police-Free Schools.

- Florida Senate Bill 7030: Implementation of Legislative Recommendations of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission. Final Report of the Federal Commission on School Safety.

- Beger, R.R. (2003). “The Worst of Both Words,” Criminal Justice Review, 28, 336-340.; Nolan, K. (2011). “Police in the Hallways: Discipline in an Urban High School”.

- Meyer, M.J. & Leone, P.E. (1999). “A Structural Analysis of School Violence and Disruption: Implications for Creating Safer Schools”. Education and Treatment of Children. 22, 333-352.

- Wilson, D. (2004). “The Interface of School Climate and School Connectedness and Relationships with Aggression and Victimization” Journal of School Health. 74(7), 293-299.

- Saldana, J. (2013). “Power and Conformity in Today’s Schools,” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 3(1), 228-232.

- See, e.g., Nance, J. (2015). Students, Police, and the School-to-Prison Pipeline. University of Florida Levin College of Law.

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). “A Review of School Climate Research.” Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 357-385.

- Fronius, T., Persson, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2016). “Restorative Justice in U.S. Schools: A literature review.” WestEd Justice and Prevention Center. Jain, S., Bassey, H., Brown, M. A., and Kalra, P. (2014). “Restorative Justice in Oakland Schools: Implementation and Impact.” Oakland Unified School District.