by Steven Barnett & Andrea Kent

National Institute for Early Education Research

Context

High-quality early learning experiences have the potential to improve a child’s life trajectory into adulthood. Broad, persistent effects have been found for learning, development, school success and educational attainment, social behavior, health, and even adult earnings. Early care and education (ECE) programs can provide experiences that enhance cognitive, social, and emotional development prior to kindergarten entry compared to outcomes for children who experience only home care or who attend low quality tending low-quality ECE. These benefits are particularly important for children from families with lower incomes and lower parental education levels, as by kindergarten entry their development lags significantly behind those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. High-quality ECE can narrow this gap. However, such benefits depend on sufficiently high quality as studies have found few lasting positive gains when ECE quality is not high, and low-quality ECE programs can even have persistent negative impacts on development.

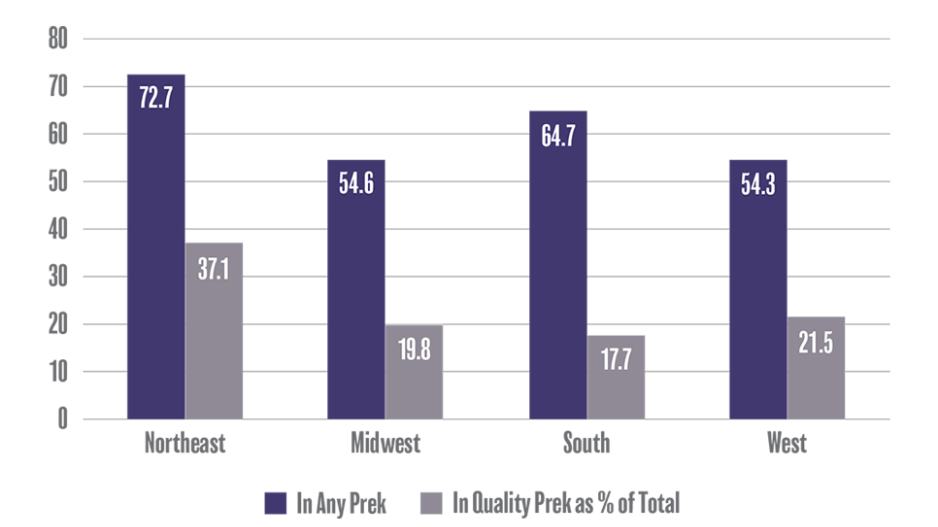

In the United States ECE quality typically is not high. Public programs offered by local, state, and federal governments through public pre-K, subsidized childcare, and Head Start seek to increase access to ECE and to raise quality. Although such programs positively impact access to high quality, they do not yet reach even most children in poverty nor do they ensure that most public programs are high quality. Also, public provision varies greatly by age and location. In 2017-2018, 40% of the nation’s four-year-olds were enrolled in state-funded pre-K or Head Start compared to only 14% of three-year-olds. Enrollment dramatically differs by state in part because of differences in the level of state support for public programs. Quality standards vary greatly across states, though few set high standards. For example, only three states met all 10 of the NIEER benchmarks for minimal quality in 2017-2018¹. Enrollment at age four in any ECE and high-quality ECE by region is depicted in figure 1.

Evidence

Decades of research finds that high-quality ECE programs have positive short-term and long-term outcomes for children. Three seminal studies provide evidence from preschool through adulthood: the HighScope Perry Preschool, the Chicago Child-Parent Center, and the Carolina Abecedarian studies. The Perry and Abecedarian studies are true randomized experiments, but with small samples and highly intensive programs. The Chicago study is large-scale and focused on a program similar to some public programs today. They found that children who attended had significantly higher cognitive abilities as measured by standardized tests from preschool through high school. These studies also found that children who attended were much less likely to be placed in special education and/or retained a grade in school. As adults, those who attended these ECE programs had higher levels of employment and income, and in two of the studies had lower rates of arrests. Many other studies add to and support these findings:

For Results at Scale, Quality Matters

- High-quality large-scale public programs produce both short- and long-term improvements in learning and development. Examples of programs found to be effective include state-funded pre-K in New Jersey, North Carolina, and Oklahoma. Large-scale public programs in Boston and Tulsa have been found to produce gains equal to a half- to a full year of learning in reading and math.

- High-quality public programs at scale can be sound public investments with economic returns averaging $3 or $4 to 1. Even though somewhat lower than the extraordinarily high returns found for small scale programs, that is more than enough to warrant investing in quality public ECE.

- Effective ECE programs provide sensitive and stimulating interactions between adults and children through intentional, directed, and focused teaching, especially one-on-one and in small groups. This requires highly capable teachers who are adequately supported in continuous improvement of their practice.

- Program standards for teacher qualifications, class size and ratio, and other structural features of programs can increase the likelihood that programs are effective, but do not by themselves guarantee quality. Other supports for quality from adequate compensation to coaching and the use of data on learning and teaching also influence program quality and effectiveness. Substantial investments in raising quality can produce large improvements in ECE quality associated with strong learning gains for children.

Dosage and Duration Matter

- In a comparison study utilizing the outcomes of children enrolled in the Chicago Child-Parent Centers (CPC) for full-day and for half-day programs, the full-day programs produced significantly stronger outcomes than did the half-day programs in the following areas: math, language, and socioemotional development. Children who attended the full-day program also had higher rates of attendance (86% vs. 80%) and lower rates of chronic absences. (Reynolds et al., 2014)

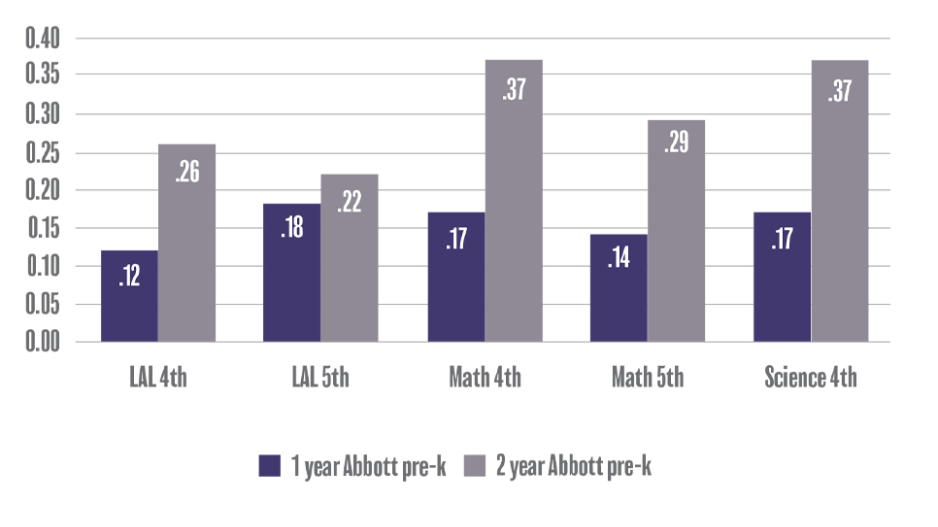

- Starting earlier leads to larger gains. The figure 2 depicts the effects on the achievement of the high-quality New Jersey Abbott Preschool Program, which indicated that two years of high-quality pre-K produced larger long-term gains than one.

- The Abecedarian Study began in infancy and found positive effects of the preschool program on intellectual development and academic achievement through age twelve. The long-term cognitive effects of this program are among the largest found by research.

All Children Benefit

Children in middle-income families can benefit from high-quality ECE, not just children in low-income families, though economically disadvantaged children tend to benefit more. Moreover, children in families between poverty and the median income level have even less access to high-quality ECE than children in poverty.

When ECE programs are low-quality, children in middle-income families may experience negative consequences. Public policies that increase participation in low-quality ECE can be harmful.

Children from families where English is not the dominant home-language make particularly large gains in high-quality ECE.

Bottom Line

The most successful way to promote equity in schools and improve outcomes for children is to invest in quality and start early. Mediocre or poor-quality programs do not produce the same results.

Related Research

Comprehensive Review of Research

Meloy, B., Gardner, M., Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Untangling the Evidence on Preschool Effectiveness: Insights for Policymakers.

Quality and Persistent Effects

Yoshikawa, H., Weiland, C., Brooks-Gunn, J., Burchinal, M.R., Espinosa, L.M., Gormley, W.T., Ludwig, J., Magnuson, K.A., Phillips, D. and Zaslow, M.J., 2013. Investing in our future: The evidence base on preschool education.

Eight State Pre-K Study

Barnett, W. S., Jung, K., Friedman-Krauss, A., Frede, E. C., Nores, M., Hustedt, J. T., Howes, C., & Daniel-Echols, M. (2018). State Prekindergarten Effects on Early Learning at Kindergarten Entry: An Analysis of Eight State Programs. AERA Open.

Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Early Education Interventions

Camilli, G., Vargas, S., Ryan, S., & Barnett, W. S. (2010). Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teachers College Record, 112(3), 579-620.

Economic Returns

Ramon, I., Chattopadhyay, S. K., Barnett, W. S., & Hahn, R. A. (2018). Early childhood education to promote health equity: a community guide economic review. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP, 24(1), e8.

Examples of Best Policy/Practice

Creating a System of Quality ECE - Barnett, W. S., & Frede, E. C. (2017). Long-term effects of a system of high-quality universal preschool education in the United States. In H.-P. Blossfeld, N. Kulic, J. Skopek, & Triventi (Eds.), Childcare, early education and social inequality: An international perspective (pp. 152–172). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Preschool 2.0

Multimedia

High Quality PreK: The Road Less Traveled Growing and Learning in Preschool

Author

Steven Barnett, Senior Co-Director

Andrea Kent, Research Project Coordinator

National Institute for Early Education Research

Footnotes

-

Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Barnett, S. B., Garver, K. A., Hodges, K. S., Weisenfeld, G.G., DiCrecchio,(2019). The state of preschool 2018: State preschool yearbook. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research.

-

Barnett, S. W. & Frede, E. C. (2017). Long-term effects of a system of high-quality universal preschool education in the United States In H. Blossfeld, N. Kulic, J. Skopek & M. Triventi (Eds), Childcare, Early Education and Social Inequality: An International Perspective (pp. 152-172). Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited

-

Dodge, K. A., Bai, Y., Ladd, H. F., & Muschkin, C. G. (2016). Impact of North Carolina’s early childhood programs and policies on educational outcomes in elementary school. Child Development 88(3), 1–19.

-

Gormley, W. T., & Gayer, T. (2005). Promoting school readiness in Oklahoma an evaluation of Tulsa’s pre-k program. Journal of Human Resources, 40(3), 533-558.

Gormley, W. T., Phillips, D., & Anderson, S. (2018). The Effects of Tulsa’s Pre-K Program on Middle School Student Performance. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37(1), 63-87.