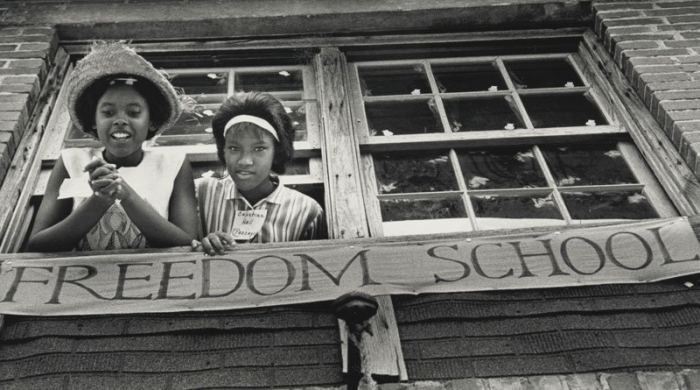

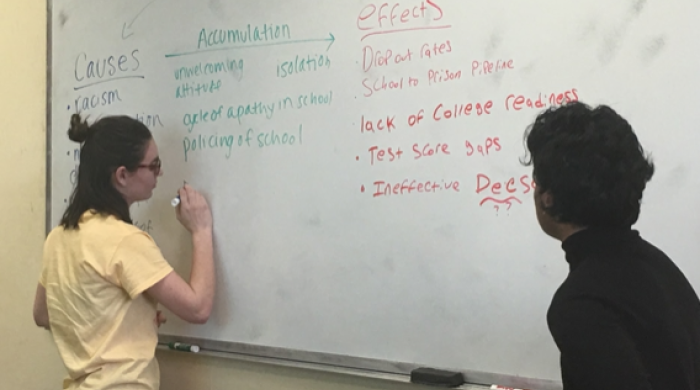

Youth voice sessions (held in partnership with adults) consist of a systematic anti-racist, progressive curriculum that sparks a socio-political-historical understanding of current issues through data, literature, and deep cross dialogue. Before these lessons and conversations take place, it is necessary to create a generative space.

Creating a Contact Zone

Before diving into the intense work of pulling apart the threads of disproportionality it is necessary to form a safe, supportive, trustworthy and loving environment to do this work. Equity work requires a conducive environment, which is often referred to as a “safe space” or even a “brave space” where students are meant to feel emotionally and physically safe and supported despite differences. Unfortunately, too often, these “safe” spaces silence students from speaking their truths for the fear of breaking up “peace” within a space while their social identities risk erasure and marginalization. Equity work is not necessarily “safe.” Students risk invoking the anger of teachers and administrators that have control over their academic trajectory and their security within the school community. The youth take on this risk while reliving traumas as they unpack their experiences. A “brave” space often encourages participants to speak out about difficult topics but does not take power differences of social identities into account. Instead, a contact zone is an intentional space of intergenerational, multi-racial, and diverse participants that engage around politicized topics. In a contact zone, dynamics of power and oppression are recognized, and those with more privilege are called in to ally with those who have marginalized identities. In this section, we flesh out what a contact zone is and how we formed it.

Background

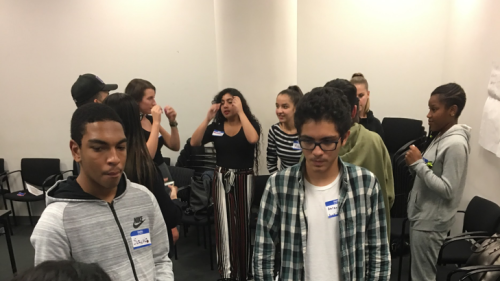

YTAC-D consisted of a diverse group of 9-12th grade students from across New York City. Some students represented high performing and predominately White and Asian schools, and some students represented predominantly Black and Brown schools that were under-resourced. Y-TACD students self-identified as Black, White, Asian, and Latinx. Within the racial categories, ethnicities varied. Some students discussed their Jewish, Afro-Latinx, Filipino, Bengali, African American, Dominican, or Puerto Rican backgrounds. Others held mixed-race identities. A handful of students identified themselves with the LGBTQ community.

Forming a “Contact Zone”

We draw on Maria Torre’s concept of a “contact zone” to form a safe and generative space for our equity work. Torre and Fine note that, “By framing our PAR collective as a contact zone, we create a politically and intellectually charged space where very differently positioned youth and adults are able to experience and analyze power inequities, together” (2008, p. 24). Our space was indeed politically and intellectually charged given our different identities, not just racially and socioeconomically but age, experience and others. These “invisible” factors were very much a part of our space and were not to be ignored. We find this contact zone critical as Torre wrote,

Before the group is critical of systems and challenges in our institutions, the individuals have to be critical of themselves. Members must challenge themself to think about their own biases and how they came to understand the world around them. Those with white privilege, male privilege, heterosexual privilege, and other privileges have to interrogate their positionality and be co-conspirators[1] for the more vulnerable identities in the room. In YTAC-D, we had to build real solidarity before pushing for larger-scale educational equity reform. This means (as Torre put it):

- Connecting “personal struggles” with historic struggles for justice

- Converting individual experiences of pain and oppression into structural analyses and demands for justice

- Interrogating the unfairness of privilege

- Linking activist research to youth organizing movements for social justice

Students had ample opportunities to share out about personal experiences. These share outs were important in building connection and community but also helped us understand a larger context by situating personal experiences within a historical and political pursuit for equity.

Learning about Each Other

Because of our differences, YTAC-D intentionally set up an environment where we came to know each other and trust each other. In each meeting, we took some time out to purposefully build community in order to establish an environment rooted in respect and love. For instance:

- We learned each other's names and their origin

- Everyone takes a turn to share the meaning of their name

- Discussed our experiences in our respective schools

- Explored each other’s racial and cultural backgrounds

- Share about each other’s identities

- Established community norms (a set of practices rooted in a sense of shared values and beliefs that foster respect and love for one another). The norms should be created together. Below are a few of the community norms we charted out at one of our first meeting:

- One mic

- One person speaks while everyone else listens

- Step up-step back (etc)

- If you are talking and taking too much space more than others, step back. If you are silent most of the time, step up.

- Know and check your power/privilege

- Those with privilege reflect on how their experiences are impacted by societal advantages such as white privilege, heteronormativity, and patriarchy, etc.

- Everyone plays a role

- Shared leadership and responsibility for everyone involved

- “I” statements

- Challenge others but seek understanding, not an argument

- One mic

- Sat in a circle as much as possible to interrupt hierarchy

- Allowed members to participate in a variety of ways

- Small group interactions

- Verbal, written or artistic expression

Through community building and establishing norms, we established a positive rapport with one another where we could safely disagree with one another and learn from each other’s perspectives. Students remarked during our meetings that they were glad to learn about each other’s different experiences, especially given that their own school communities are like a “bubble” considering the racial and class segregation of the NYCDOE

YTAC-D aligned with Torre’s description of a contact zone as “a messy social space where differently situated people ‘meet, clash, and grapple with each other’ across their varying relationships to power (Pratt, 1991: 4)”

By viewing ourselves as a “contact zone” we learned greatly from each other. We felt safe to show up as who we were, interrogating ourselves (who I am, who I’m not, who I want to be) in order to build loving and meaningful relationships with each other. This was necessary to take a deep dive into understanding and addressing disproportionality.

This group did not just give me a sense of home. Since everyone was close and shared similar ideas on different topics, and respectfully disagreed with each other. But the sense of belonging, to know there are teenagers with similar mindsets. It is so easy to feel misunderstood in a school where you are the only one that sees the injustice and wants to do something about it but does not have the proper support system to do so. But this group finally gave me a haven where everyone sees the unjust, wants to make a difference, and an amazing support system.

[1] Whereas ally-ship is performative or self-glorifying, co-conspirators use their power and privilege to stand in solidarity with vulnerable groups to confront anti-Blackness and injustice. A co-conspirator functions as a verb, not a noun. (Love, 2019, p.117)