By Hui-Ling Sunshine Malone, Demiana Rizkalla, Ellie Bartlett

Introduction

“The more students work at storing the deposits entrusted to them, the less they develop the critical consciousness which would result from their intervention in the world as transformers of that world.”

Despite the Brown vs Board (1954) decision that gave the nation hope in eradicating racist schooling practices, currently, Black and Brown students are disproportionality disciplined, underrepresented in accelerated coursework, and overrepresented in special education and remedial courses (Skiba et al., 2016; Fergus 2016). In addition, mainstream curriculum promotes the erasure of racial, cultural, and linguistic diversity for the purpose of assimilation into a white middle-class society (Paris, 2012) supporting the longstanding opportunity gap between Black and Brown students and their White and Asian counterparts (Carter & Weiner, 2013). Today, the majority of students in the United States are still in de facto segregated schools. Historically, white flight, redlining, and other racist housing practices (Coates, 2014; Rothstein, 2017) have shaped the present zoning of schools. UCLA’s Civil Rights Project released in their special report, “Harming Our Common Future: America's Segregated Schools 65 Years after Brown” that despite shrinking enrollment of white public school students, white students are still the most segregated stating, “white students, on average, attend a school in which 69% of the students are white, while Latino students attend a school in which 55% of the students are Latino” (Orfield et al., 2019). Despite the richly diverse population of New York City, where our study resided, New York City public schools is the most segregated school district in the nation (Kirkland & Sanzone, 2017).

Today’s students are well aware of these issues and deserve the platform to discuss and address them collectively. Critical educator Paulo Freire believed that education should serve to question the world, read the world and read oneself and their positionality[1]. One way to read the world in relation to ourselves is through Participatory Action Research (PAR), which is rooted in Freire’s concept of conscientizacao, or, critical consciousness (Lykes & Mallona, 2008). Only when those most marginalized reclaim power and have control and decision-making power, can radical change happen.

This manual stems from the formation of the first-ever youth arm of NYU Metro Center’s Technical Assistance Center on Disproportionality (TAC-D) that birthed the Youth Technical Assistance Center on Addressing Disproportionality (YTAC-D). The group represented 15 different schools across the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) that set out to explore disproportionality in hopes to dismantle it. Through participatory action, YTAC-D critically examined the structural inequities of their education system in hopes to advance schooling to be more humanizing for all students. Ultimately, this meant that students advocated to feel respected, affirmed, welcomed, and validated in schools through recommended policies such as culturally responsive curriculum and restorative justice discipline practices. This work is continuing and evolving with Innovations in Equity and Systemic Change (IESC), a restructuring of TAC-D, and NYCDOE partners and students. Innovations in Equity and Systemic Change (IESC) at the Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools at New York University provides professional development, technical assistance, and consultancy to educational institutions in general and special education. Our mission is to advance equity by disrupting, dismantling, and eradicating disproportionality by building the capacity of educators to implement Culturally Responsive Sustainable Equity-Based systems that meet the needs of every student and family.

The Problem: What is Disproportionality?

As defined by the US Department of Education, disproportionality is:

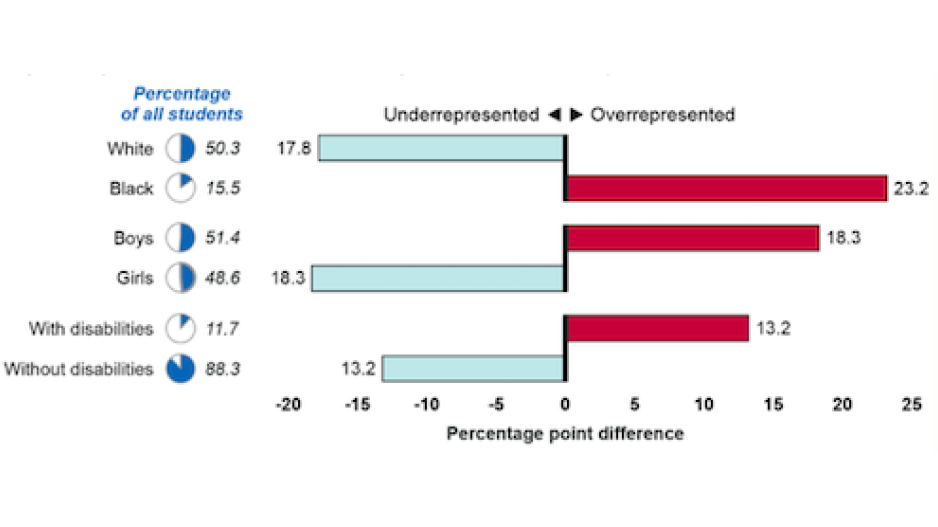

As demonstrated in Figure 1, a 2018 U.S Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that Black students, boys, and students with disabilities are disproportionately disciplined according to their analysis of the most recent civil rights data (GAO Report, 2018). The disparities existed “regardless of the type of disciplinary action, level of school poverty, or type of public school attended” (GAO Report, 2018, p 1).

Students Suspended from School Compared to Student Population, by Race, Sex, and Disability Status, School Year 2013-14

This chart shows whether each group of students was underrepresented or overrepresented among students suspended out of school. For example, boys were overrepresented by about 18 percentage points because they made up about 51% of all students, but nearly 70% of the students suspended out of school.

YTACD Figure 1

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Education, Civil Rights Data Collection. | GAO-18-258

Although the report is relatively recent, the findings are not novel. Racial disparities in school settings and its consequences around discipline have been widely cited in the literature. This includes work on Black girls and boys such as Monique Morris’s book Pushout and the African American Policy Forum #BlackGirlsMatter Report that both document how Black girls are pushed out and over-disciplined in schools. Scholars such as Russell Skiba and Edward Fergus have also written extensively about addressing disproportionality in schooling, interrogating the intersections of race, class, and gender[2]. As children are pushed through the cracks of inequities in their schooling, they are vulnerable to being funneled into America’s prisons (Kim et al., 2010). Black and Brown children who are disproportionately suspended often take up an adverse relationship to school that eventually prevents educational opportunities and lends toward unfulfilled potentials. This trend begins early. For example, a Yale Child Study found that early childhood educators were more likely to notice “behavioral issues” of Black students as young as three and four years old compared to their white counterparts (Gilliam et al., 2016). To that end, Black students are viewed as a threat before seen as children deserving of a nurturing education. This harm caused to vulnerable[3] children is a result of an educational system that excludes them through over-policing and hypercorrection that aims to “fix” youth instead of holding them as brilliant and valuable.

The urgency of this rampant issue is why we charge school districts to have a commitment to youth voice and youth-adult partnerships.

About this Manual

This manual is not a step-by-step instruction manual on how to implement youth voice and equitable youth-adult partnerships within our schools and districts. Instead, we consider this a manual of guidelines and suggestions. We do not believe in a “one size fits all” solution and are acutely aware that schools and districts have their own unique characteristics. This work should ultimately center your own contexts, capacities, and most of all--your youth--toward addressing disproportionality. However, we do believe that despite the circumstances of your particular educational context, you can and must do the work to center your most vulnerable youth and shift mindsets, policies, and practices that will lead to more equitable outcomes. This work will not be done overnight. It takes investment, commitment, hard work, and dedication along with capacity building and systemic changes. We hope to provide an example and inspiration toward “doing the work” that is necessary for radical change in order for every child to meet their potential.

Manual Units

[1] Positionality is the social and political context that creates your identity in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability status. Positionality also describes how your identity influences, and potentially biases, your understanding of and outlook on the world

[2] Edward Fergus book and Russell Skiba book

[3] The term “vulnerable” is used to indicate a person who is subject to exclusionary practices and biases rooted in racism, homophobia, misogyny, transphobia, religious discrimination, language discrimination or xenophobia