Before launching into the work of interrogating and addressing disproportionality, it is necessary to establish a strong and sustaining youth-adult partnership. Youth are ultimately centered in this work. They provide guidance, leadership, and knowledge in helping adults understand their experiences so that adults can fully support students.

What does a youth-adult partnership look like?

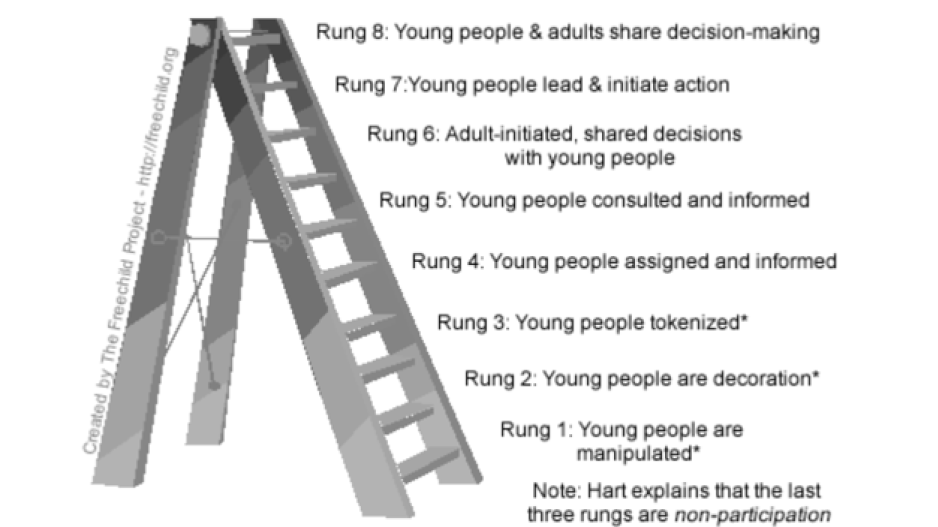

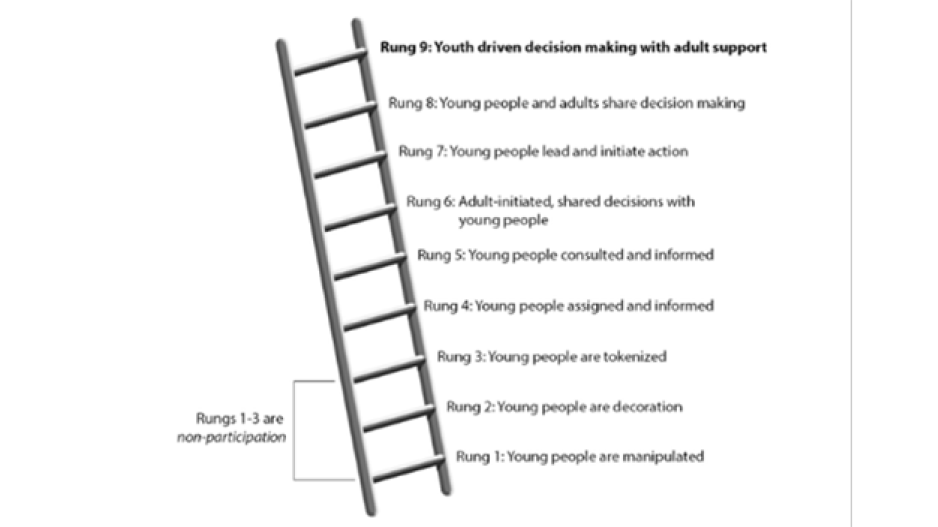

A productive youth-adult partnership is possible when the adult supports youth and youth voice. Often, “equality” is viewed as the end goal of a youth-adult partnership, however “equality” simply does not go far enough to redress power issues. When student voice is second to those of adults, the decision-making power of youth is quickly diminished and their inclusion in these spaces becomes performative, which emphasizes the “dramatic form of asymmetry between youth and adults” (Mitra, 2009 p.409). Adults do not have the embodied knowledge that youth have of the student experience. In order to truly support youth voice, adults must recognize that students are the highest authority on their own experiences and needs and therefore youth and adults cannot have equal roles in creating change. This view of youth-adult partnerships pushes past Hart’s “Ladder of Young People’s Participation” toward what we call a “Youth-Driven Ladder of Participation” (see Figure 2). We propose a 9th rung of “equitable partnerships” where youth drive decision-making and adults support their efforts to enact radical change to advance educational justice. This means that the adult’s role is to fully support the youth, as youth initiate decision-making and surface issues of concern.

Roger Hart's Ladder of Young People's Participation

Adapted from Hart, R. (1992). Children's Participation from Tokenism to Citizenship. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre

Youth-Driven Ladder

Adapted and modified from Hart, R. (1992). Children's Participation from Tokenism to Citizenship. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Establishing the Partnership

To establish the partnership a school or district representative must make a commitment to address educational inequity. This adult representative, or adult partner, is ideally a separate paid position or structured within an existing job description. The adult partner coordinates logistics of the group to move the work along. Ideal characteristics of the supporting adult includes (but are not limited to):

- A district representative or school representative (depending on the scope of the project)

- Reliable, trustworthy and invested in equity

- The adult (or team of adults) should be deeply invested in equity-- meaning they have a sense of what disproportionality is and its root causes. They are not fearful to address issues such as race and racism and other issues of power and privilege. They are willing to learn and grow with the immediate group and surrounding colleagues.

- The adult must also be willing to challenge their colleagues and superiors to stand in solidarity with youth toward the end goal of equitable schooling structures.

- The adult has done their personal work around identity, race, power, and privilege. The adult continues this internal interrogation throughout their work with youth

- Presents follow-through

- Helps work with youth to coordinate meetings and other events

- Has access to resources such as food and space

- Holds other adults—both those intimately involved in the project and those who are not—accountable for filling their roles and fulfilling promises so that youth can adequately do their work.

- Builds bridges between youth and education stakeholders

- Has a positive reputation among students around connecting with youth, being responsive to youth, and is a recognized advocate of students from historically marginalized communities.

- Handles logistics such as parent permission forms and communication with schools

- Is familiar with the “lay of the land”

- This person understands the structure of the school and district, politics of the district and knows the right people to get things done (chain of command)

- Grounds their trust in youth by stepping back and encourages youth leadership in the immediate group, throughout classrooms, and other educational spaces.

In our case, the youth-adult partnership existed between NYCDOE and the NYU Metro Center. Our adult team consisted of three dedicated NYCDOE personnel (a white woman, a white man, and a Black woman) and one lead Metro representative (a biracial Black and Asian woman) who created curriculum and facilitated meetings. Together the adult allies partnered with NYCDOE high school students to interrogate disproportionality in schools, conduct participatory action research and present their work at various conferences.

It is key that everyone is invested in the work and knows their designated role and responsibilities in order for this work to be sustainable. This means that those involved safeguard consistent time commitments and energy toward supporting and seeing through the mission, values, and activities of the youth-adult equity team. Members work together and look for opportunities to turnkey the work of the group in their classrooms and beyond. In addition, it is best when the school and district leadership are aware of the work and support.

In some cases, the group may want to identify a neutral space for meetings, such as a local library, community center, or university facilities. This way, students can begin the conversation safely from school and district leadership. In neutral territory, students can take the lead on issues without fear of infiltration and negative opinions from unsupportive school adults.

Recruitment of Students

After there is a committed adult (or team of adults) with a clear understanding of an equitable youth adult partnership, students are recruited. What is the ideal make up of students who should be involved in this work? Ideally, all students would take some role in this work. Realistically, however, not all students will join enthusiastically either due to lack of interest, lack of trust, or other time constraints. Therefore, this work should not be obligatory toward students. There should be multiple pathways for students to participate given their capacity and interest. With that said, a core group of committed students is the key to getting things done.

Students recruited to this group should ideally be representative of the student body in regards to race, socioeconomic status, gender, sexuality, academic status, grade level, leadership involvement, school engagement, and disciplinary status. The student body is not a monolith- students go into school with different sets of circumstances and identities that determine their experience within the learning environment. Black students experience school differently than white students, than Asian students, Latinx students and Indigneous students, etc. Some students may have special needs or vary in gender expression, therefore, it’s important to have representation. Administrators cannot possibly understand all of the different youth voices and experiences that make up their schools. Students who are marginalized by school administration tend to be more comfortable sharing their truths with other students rather than authority figures because they may share similar experiences and will not fear punishment. Therefore, students are more likely to have access to the voices of their peers rather than adults.

That being said, the group must center the voices of students who are most marginalized even if they are in the minority. Students who have the most difficult time with school are needed voices, as white or privileged students cannot fully grasp the experiences of ostracized groups. It was important for white students to understand whiteness, how it functions, and to explicitly decenter whiteness in our conversations. For instance, in a predominately white school, it is necessary for Black and Brown voices to be heard and supported even if they are a smaller percentage. We believe that uplifting marginalized students will provide a more equitable and humanizing experience for all students. It is necessary that in this partnership, Black and Brown and other vulnerable students are not silenced.

When recruiting for students, adults tend to reach out to pre-existing student groups, such as student government.We urge you to look beyond such groups. Unfortunately, students who have the highest authority to speak on issues of inequity are often left out of these existing “student voice initiatives” or other leadership organizations. This is not to say that student leaders should not join youth-adult equity teams, but that such students should not be the only ones cherry picked for this work. Students of interest are those most impacted by the lasting legacies of segregation and marginalization experience excessive discipline, tracking, a lack of resources, and discrimination from both teachers and administration. Often, they are neither invited to these spaces because of the biases that exist against them (“bad” or “troubled” kids) nor are they enthusiastic about joining them due to a mistrust of the school. Further, if this is a district wide initiative, students should be recruited across the region given that segregation is rampant in school districts nationwide.

Beyond recruitment of these students, school adults should work toward deconstructing bias against students who have been marginalized by the education system. By forming a youth-adult partnership, school adults begin the process of acknowledging that the educational system has disproportionately disciplined and marginalized vulnerable students while uplifting privileged groups. School adults should question the ways in which they uphold a system that views vulnerable students as less capable and less valuable.

Youth Role

Youth leadership in school equity initiatives is the rightful role of students. Biases against youth because they are younger ignores the brilliance and capability of youth. Students know when they are not taken seriously by adults. If the youth-adult partnership is not rooted in trust, then the equity partnership will not succeed.

Youth enter this partnership with knowledge, experiences, and the ability to communicate with other students in a way that adults cannot. For instance, students are uniquely affected by school policies and practices such as teacher-student relationships and curriculum and instruction. Youth can often gauge the effects of school culture better than an administrative assessment tool because of their embodied knowledge of their school experience. For example, one of our students, Monique, who is one of the few Black students at her school, explained to us and her administration the discomfort and discrimination she experienced with her school’s disciplinary policy on durags and bonnets (Black hair care accessories). Because the school’s policies were rooted in whiteness, Black students who refused to assimilate were punished. Monique and her peer’s insights were invaluable in raising those points to reform school culture to support Black students and all students at her campus.

Therefore, youth have a critical role in this partnership. Some roles and responsibilities include:

- Creating the mission, vision, and values of the organization

- Planning or co-planning meeting sessions and topics

- Facilitating or co-facilitating planning and general meetings

- Hosting meetings with school leadership to turnkey information

- Disseminating information to youth beyond the group

- Determining the trajectory, goals, and activities of the team

Adult Role

Adults enter this partnership with years of experience, an intimate knowledge of the inner workings of the system, and an investment in equity. Again, the idea is for adults to support students and lead this work toward transformational change at an institutional level. Adult roles and responsibilities include but are not limited to:

- Providing resources and informing students of systemic racism and oppression in schools (policies, budgeting, politics) or other barriers so that they can tackle them together.

- Offering students literature and history related to the current educational context

- Providing students with necessary contact information for key administrators and decision-makers that are gatekeepers for critical change.

- Providing access to data (e.g., achievement data, discipline data, student interviews)

- Serving as a liaison between students and their adult counterparts

- Pushing policy change at school and district levels

Overall, adults should use their power to support and inform youth choices, not overpower them

Unit 1 Conclusion

In order to have a sustaining and solid youth-adult partnership, it is important for everyone to understand their roles. Adults must listen to youth and let their experiences guide the work. Further, adults must have an understanding of inequity and can offer insight into their knowledge on the socio-historical political landscape of schooling to deepen conversations and make radical change to transform the schooling experiences of youth.

Now that we have laid out the expectations of a sustaining equitable youth-adult partnership, we move toward a common understanding of a respectful and nurturing space when youth and adults come together to do educational equity work. We adapt the concept of “contact zone” to guide us toward establishing a generative youth-adult space during working meetings.