An Interview with Dr. Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz about Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education

Edmund Adjapong, Kisha Porcher

This interview highlights how Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education can be utilized to consider new possibilities for and address inequities in urban schools. It discusses the importance of positive teacher identity as a prerequisite for effective CR-SE and Dr. Sealey-Ruiz’s framework of the Archeology of Self, which she describes as a framework that encourages educators to dig deep, peel back their layers, and explore how issues of race, class, religion, gender, sexual orientation live within them.

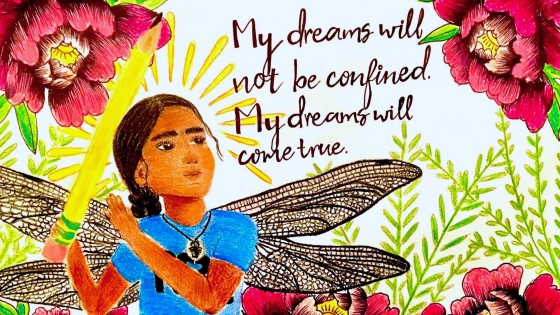

Leslie Martinez

Kisha: Right now, there is a big focus on Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Education as a framework to address inequities in schools. How do we empower teachers to develop skills and agency to engage in culturally responsive sustaining practices?

Yolanda: I think for those of us who have been on the front lines, we continue to do what we’ve been doing. That is to be really clear about no matter what we call it, this is about inequities that have been persistent, certainly for centuries that Black people have been in this country, but most notably since integration. We know, and we have always known, that school systems have not served Black and Brown children, particularly Black children, the way that they deserve to be served. We know that the schools have been structured with inequality in its roots and its blood. What I think is important with the movement, the nationwide movement is, number one, giving props to Gloria Ladson-Billings, Geneva Gay, even going back to James Banks and Cherry McGee Banks, Sonia Nieto, all of those folks and up to now with Bettina Love and Patricia Williams giving us the language to name it. To be very clear, that no matter what we call it, culturally responsive, culturally relevant, culturally sustaining, culturally responsive and sustaining, the bottom line is, it's about attacking the inequities. We must continue what warriors have been doing, hold on to the language even as it shifts, and for me, it comes back to the Archeology of Self. I have to tell you that’s becoming more and more real to me that people are not doing the self-work. We have been conditioned, particularly in professional development, and working with pre-service and in-service teachers to go straight to the curriculum. What’s your curriculum like? Does it include this? Does it include that? Do you know that theory? And we need all of that, but if the repository for that, which is the body, the heart, the mind, the soul is not in sync with what the theory, and curriculum, and curricula offer, it’s not going to work.

Kisha: As a teacher educator, I remind my students of the importance of the Archeology of Self as the foundation of the work; however, I am met with resistance from students. They are focused on the best practices or a “toolkit” that they can memorize as the magic bullet to “fixing” students of color. My students only see themselves as teachers, in which they separate their personal identities from teaching. I have engaged my pre-service teachers in PhotoVoice assignments in which they unpack their identities utilizing photographs and reflective questions. They capture photographs and reflect throughout the course about their identity, while exploring the assets of their students and communities, and culturally responsive and sustaining practices. This assignment is an example of a CR-SE assessment, as pre-service teachers are given the opportunity to express their diverse identities and experiences as assets in understanding how to prepare to become teachers of diverse students. In the course design, I ensure that students understand that this is a cyclical and reflective practice process - we have to continue to unpack who we are, explore the assets of our students and enact culturally and responsive sustaining practices. Students are given an opportunity to submit assignments and assessments multiple times to demonstrate CR-SE, as the work of self and understanding multiple expressions of diversity. At the end of the course, the students recognize the importance of self-work as an on-going lifelong journey.

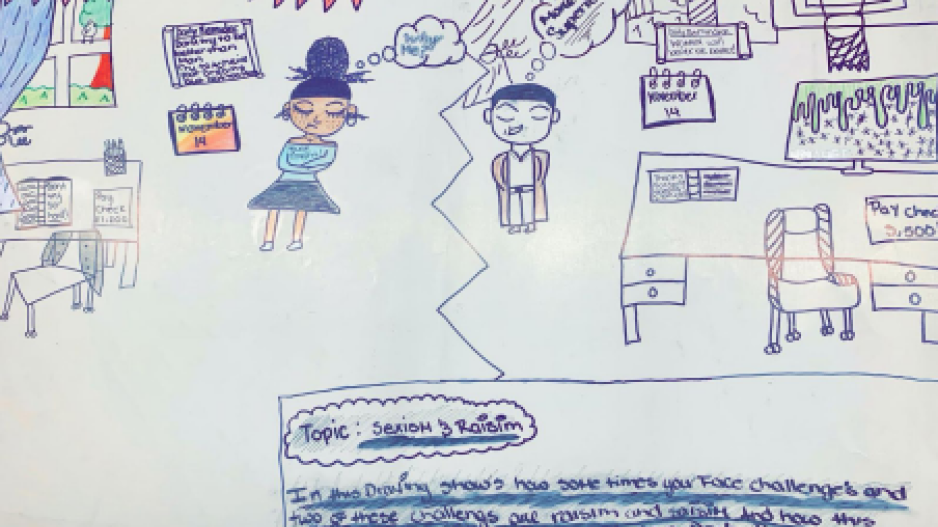

Edmund: I think it’s very important to share stories and experiences of diverse groups of people. In my work with pre-service and in-service teachers, I use various forms of multimedia to share stories that highlight inequities. I love to use documentaries, videos, song lyrics, to highlight experiences of historically marginalized groups. This pedagogical practice moves beyond the traditional examples of assessments, assignments, and instructional materials, by incorporating multiple modes of learning. This is an example of CR-SE as the cultures, assets and inequities of students are centered in the curriculum. I model for preservice teachers the importance of utilizing these strategies, as a model to incorporate the assets of students within the curriculum. I agree with you Yolanda when you say CR-SE work is about attacking inequities. We have to prepare educators to recognize inequities, both systemic inequities, and inequities that they have put in place through practice and pedagogy, then provide support in how they can dismantle injustices. Once we can understand these experiences and empathize with them, we can focus on being part of the change to help to create better experiences for all people.

Edmund: What does the framework of the Archeology of Self look like and what is its relationship to freedom? Further, how can we use that as a framework for freedom in school and school systems?

Yolanda: Before I answer, I would like to ask Kisha about your experience in schools as it relates to learning about your history, how did it make you feel? Did you feel freer?

Kisha: It looks like an exploration of familial and cultural history. It also requires deep reflection about my own schooling experience (K-12, college, and grad school). Our past and current experiences impact how we show up in classrooms. For example, I was bussed to a primarily white high school. I remember asking my teacher are we going to learn about Black people? Her response was “you’re taking all AP classes isn’t that enough?” I was the only person pushing back. Then I went to a historically Black college, Spelman College. I grew up in the hood and never saw Black professionals. Then I was in a space with Black people whose families are Black doctors, lawyers, nurses, directors, etc. It was such a space of dissonance for me. I asked my roommate “Is that your real Dad?” I had never met my dad. These were the questions I asked, but also having to look at myself and wonder, “was my life messed up?” I knew that growing up I was poor but when I got to college, I really knew I was poor. I was trying to figure out who I was and where I fit in this space. I remember asking myself every day, do I belong here? There’s no way they let me in here, not the person who grew up with her grandma, don’t know her dad, and don’t live with her mom. In the first course I took in college, we learned about the African Diaspora. And I just kept saying, hold on, wait, you mean to tell me, we were Kings and Queens? While learning these new things about Black excellence, I continuously thought about the stark differences between my family and my life in college. I wanted to share the new things that I learned. However, my family was focused on keeping food on the table.

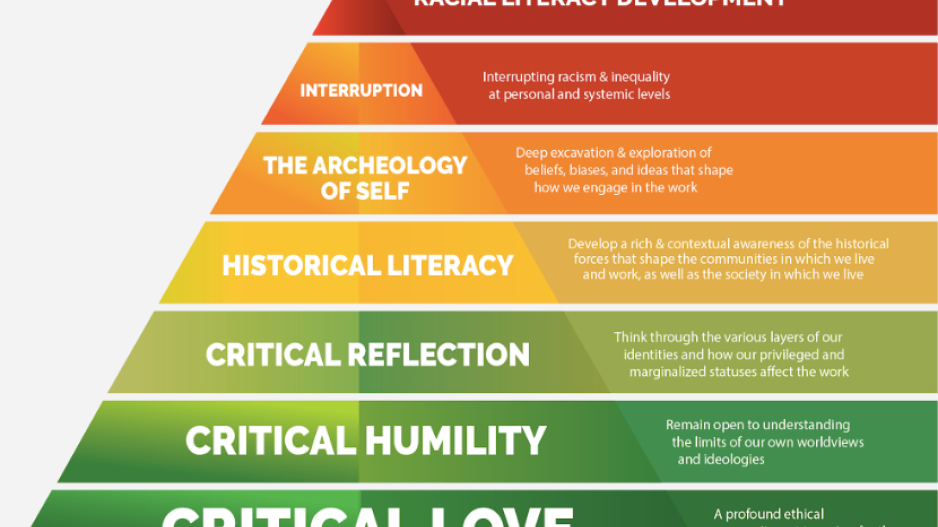

Yolanda: The Archeology of Self is truly a journey for the self. It's a framework (see Image 1). Certainly, the way that I’ve conceptualized it relates to K-12 education, but the Archeology of Self is something that is applied to all areas of life. So, for example when I talk about the Archeology of Self around love and intimacy, my artifact is my book, Love from the Vortex (Sealy-Ruiz, 2020). It is who I am as a mother and a teacher. So, it is a framework that is built on love, humility, reflection, and historical literacy. Archeology of Self is a framework of becoming what I see as ultimately, I’m hoping, of liberation, but the way it plays out in the pyramid of racial literacy development is knowing yourself within the educational context. My hope is that this framework is going to lead educators to then interrupt systems. So, you have to know yourself, you have to know history, and you have to be humble enough to recognize what you don’t know. You have to have a fundamental love for the communities that you’re serving. All of those elements or components as I’m calling them, are to help get you to this moment of self-excavation of what your beliefs are, your mindset, and values, as it relates to, in this case, education. Once you come to understand all of that, and you do that self-excavation, then you have to take appropriate action. So, for most people who decide to be abolitionist teachers (Love, 2019), warriors against inequity, they realize they are then led to interrupt racism, and that comes in different forms. We know that this thing of racism is in the air and in the water. My hope with the Archeology of Self framework is that it leads educators to be courageous, to interrupt systems and that that also offers a form of liberation.

Image 1. Archeology of Self Framework

Kisha: How do we do that self-excavation if we, in some cases as people of color, don’t really know our history, who we are, and where we come from?

Yolanda: Historical literacy is part of the framework. Kahlil Gibran Muhammad who talks about having historical literacy mostly in his book, The Condemnation of Blackness (Muhammad, 2019), looks at how systems and mostly political and police systems have been condemning Black folks from the beginning. For example, you know the so-called 13th Amendment, but then coming up with all these Trump charges to get Black people in prison, which is pretty much in another enslaved state. So, if we don’t know the history of people of color we will continue to perpetuate these systems. The Archeology of Self has to be built on something. It has to be built on the humility of understanding that you don’t know, that you have partial truth, and that you probably are operating on lies. History is filled with lies. So you have to have the humility of understanding that what you know is partial but also filled with lies, filled with mistakes.

Edmund: I agree. I think Black history is underrepresented in all educational settings. So it doesn’t surprise me that many Black folks don’t have a deep understanding of the African American experience here in the United States, but also globally. I was an Africana Studies minor in college and was able to learn about the African diaspora and African American history here in the United States. I think this grounded me in wanting to do more for my community because the reality of our history in this country is that we have never been given a fair hand. When you think about the African American experience as it relates to the premise of what this nation was built on, nothing has been fair to people of color and everything we have, we had to fight and sacrifice for. Having a deep understanding of the experiences and histories of people of color in this nation can encourage educators to be more empathic and more attuned with the historic needs of the populations of youth that they serve. Further, it will highlight the reality that education systems have never been equitable for people of color, so there’s an importance and sense of urgency to engage in pedagogical strategies such as CR-SE to really get to the root of inequities and provide better learning opportunities for our students.

Edmund: How can teacher educators and K-12 teachers empower students to develop agency to create change in their local and global communities?

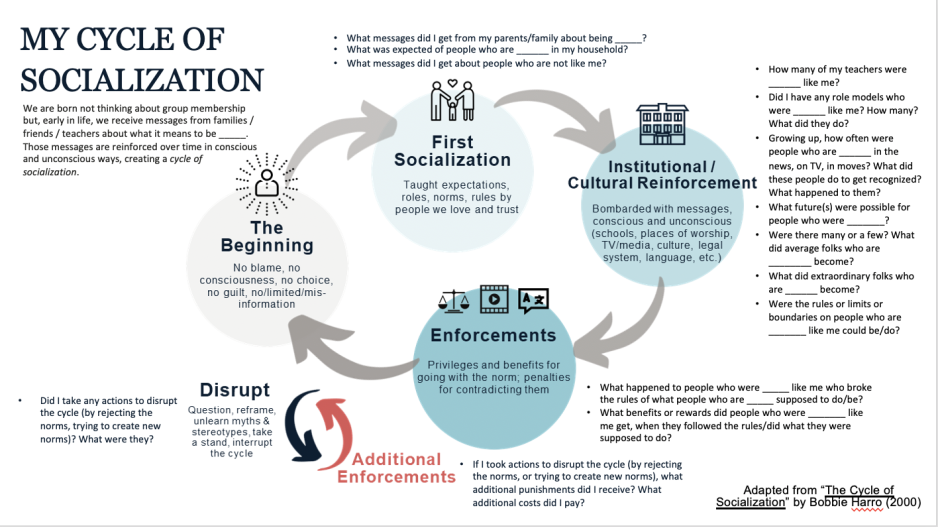

Yolanda: I don’t mean to be reductionist and simplify this, but the older I get the more I realize it is gonna have to come back always to the self. Teachers and teacher educators are not developing their own agency. How are you going to tell somebody you need to be an agent for change when you’re doing the same thing over and over? I’m thinking more and more that when we facilitate professional development, or when we engage in teacher education in our classroom, we need to be more focused on supporting teachers in developing self-plans; “self-development” plans. An example of a self-development plan, would be to explore one own’s cycle of socialization; especially around race (see Image 2 below). Teachers can begin their self-excavation by responding to the prompts. Self-development plans should be a staple assignment. For example, how are you tracking your development towards anti-racism? Physically writing stuff down, practicing it, bringing it back, discussing it with an accountability partner, and building your agency. As you uncover more about yourself, you see more. The hope is that your language changes, your questions change. I think that we have to be more deliberate in how we’re designing what we’re asking pre-service and in-service teachers to do as it relates to identity development. If teachers are actively participating and reflecting on ways they have and utilize their agency for the betterment of the community and students, it becomes easier for them to translate it into their own classroom. Many teachers lack proficiency as it relates to their own racial identity and we’re asking teachers and teacher educators to provide insight on how to harness and utilize insight to develop student agency when they're not proficient in themselves. I think we have to be very deliberate with every exercise that we ask them to engage with. Using archeology of the self as a framework to go deep, and recognizing everything we ask educators to do it comes back to the self. What racist statement have you said this week? How did it make you feel? How are you going to do it differently? Explicitly asking educators to name, and label and say very clearly, how they have been engaging in racism or anti-racism. I don’t know that our assignments do that.

Kisha: I agree. We have to model for students what we want them to do. If we want them to develop agency in their school and community, we have to demonstrate agency in our own contexts. What are we doing to empower ourselves? What are we doing to empower other teachers in the building? Our students watch us closely, to ensure that we are practicing what we preach.

Edmund: What does freedom look like? Within schools and school systems how can we achieve freedom for our most vulnerable populations?

Yolanda: You know something, I don’t think that’s so hard to answer because I think we’ve had models. I think we’ve had models with Haki Madhubuti and Carol Lee’s schools in Chicago. I think we have had models through Afrocentric education. I’m thinking back to the 90’s Benjamin Banneker, and Lester Young. I mean the freedom dreaming I think for me is how do we dream away this racism? How do we break free from the white gaze and center the Black gaze? Which I think could help us toward reimagining. Kisha, this is what you and Shamari are doing with the Black Gaze Podcast (Black Gaze Podcast, 2020). I almost want to say reacquainting with some of these models that already exist. So, I think the freedom is we are dreaming of a world where racism doesn’t exist in the way that it does and has and has limited so much of our potential. I will continue to fight that, so I think it’s a freedom fight. I think we look at those African-Centric schools. I think we look at some of the principles of Garveyism. I think we look at some of the principles of the Nation of Islam. I think we look at some of the principles of these very Black centered organizations and schools and have the freedom to get the resources. I’m not saying for white men to please hand me the check, but get out of the way. So that I can actually have the freedom to get the resources in the same way that you do. So, when we talk about freedom dreaming, we’re freedom dreaming these philanthropic organizations that have for centuries been so tightly held by Rockefellers and Carnegies and other kinds of white monies. Aspen Foundation, all of that. See that’s what makes it so difficult, because we’re fighting against history. Where are we on the timeline? We’re going against this history, that it’s like, you know taking a shank and trying to break down a wall that’s existed for 400 years. Like the Great Wall of China. That's really what we’re doing. Racism is like this great wall that we’re trying to scale but also break down. So, the question is, how do we, you know, remove some of the bricks that the wall becomes weaker? Hopefully, the generation behind us will tear down the wall altogether. That’s my hope and dream. I think we reacquaint as we reimagine. Because we have models. We have examples.

Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Education is “grounded in cultural view of learning and human development in which multiple expressions of diversity (e.g., race, social class, gender, language, sexual orientation, nationality, religion, ability) are recognized and regarded as assets for teaching and learning” (Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework). The objectives of CR-SE align with Dr. Yolanda Sealy-Ruiz’s framework of Archeology of Self, which promotes the understanding and inclusion of diverse groups. Dr. Sealy-Ruiz’s framework of Archeology of Self focuses on identity development as a precursor to engaging in effective CR-SE practices. While we agree that CR-SE is the goal to engage all students, by highlighting and challenging inequities through curricula, we believe that teachers must interrogate their identities and their life experiences as a pre-requisite to engaging in CR-SE strategies and pedagogies. More importantly, in order for teachers to gain the skills necessary to be effective in engaging in CR-SE, teacher education programs and school professional development sessions must encourage teachers to develop historical literacies, as well as explore their personal and professional identities, and as it relates to the lives and experiences of their students.

For more information about Dr. Sealey-Ruiz’s Archaeology of Self Framework: https://vimeo.com/299137829

References

Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework. (n.d.). Retrieved April 30, 2020, from http://www.nysed.gov/common/nysed/files/programs/crs/culturally-responsive-sustaining -education-framework.pdf

Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Muhammad, K. G. (2019). The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, With a New Preface. Harvard University Press.

Porcher, K. & Bertrand, S. (2020). Black gaze podcast (Audio podcast). https://anchor.fm/black-gaze

Sealey-Ruiz, Y. (2020). Love from the Vortex & Poems. Kaleidoscope Vibrations LLC.

Teach for America. (2020). Cycle of socialization: Adapted from Harro, B. (2000). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W. J. Blumenfeld, R. Castañeda, H. W. Hackman, M. L. Peters, & X. Zuñiga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice: An anthology on racism, antisemitism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, and classism (pp. 15–21). New York: Routledge.

Author Bios:

Edmund Adjapong, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor and Program Director in the Secondary Education Program at Seton Hall University, and a faculty fellow at the Institute of Urban and Minority Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. His research addresses issues of race, class, inequities in education and misperceptions of urban youth and currently focuses on how to incorporate youth culture into educational spaces, specifically on utilizing hip-hop culture and sensibilities as an approach to teaching and learning. He can be reached Seton Hall University, Jubilee Hall 441, 400 S Orange Ave, South Orange, NJ 07079, and by email at edmund.adjapong@shu.edu.

Kisha Porcher, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of English Education at the University of Delaware and the co-host of the Black Gaze Podcast. Her research focuses on three distinct interrelated areas: 1) unpacking of self and identity as foundational to teaching and learning 2) exploration of assets and conditions of Black & Brown students and communities 3) centering Blackness in community-engaged learning and teaching. She can be reached at University of Delaware, 203 Memorial Hall, Newark, DE 19716, and by email: kporcher@udel.edu.