Latinidades for a pluralistic vision of culturally sustaining education

Pamela D’Andrea Martínez, Ashantie Diaz Johnson, Lilly Padía, & María Paula Ghiso

This article explores what culturally sustaining education means for Latinx students. Drawing on the concept of Latinidades, the authors suggest that culturally sustaining education for Latinx students necessitates problematizing the boundaries of this term altogether and making visible the tensions and multiple axes of oppression around what it means to be Latinx. They take inspiration from Latinx students—including one of the authors of this article—who are challenging bounded notions of culture (such as “affinity groups”) and instead foregrounding questions about equitable practices in the day-to-day context of schools.

Nandita Ramkesar

The Protector’s Testimonio [1] #1: Falling Through Cracks of Color

I’m more than just a box. I’m an Afro-Latina who can’t enjoy affinity spaces because they are confined by four walls that have posters of powerful White women and school values. Entering a Latinx affinity space and seeing the looks I get from the other Latinas in the room with their straight hair and their “perfect ideal Latina skin,” hoping to feel some form of acceptance, I just get pushed to the corners because I am not Latina enough. Then hoping to find that “enough,” I enter the Sisters of Color affinity space with comments of “Aren’t you Spanish? Why are you here?” and “Oh, you’re half Black, you don’t walk with the same target on your back.” Getting comments like, “you don’t look Black” from one part of my culture, and hearing, “you’re too American” from the other, is part of living life as an in-betweener.

Ashantie “The Protector” is a high school senior in a public school in New York City. People call her Shy but as her testimonios reveal there is nothing shy about her—rather, this naming reflects the type of irony and linguistic play so familiar to many Latinx peoples, like calling attention to a young man across the street by yelling, “Epa, viejo!” [2] In sharing her testimonios in this article, Ashantie has chosen to go by “The Protector” because that is the role she has taken on for students who are marginalized at her school (y además it makes her feel like a superhero). While adults at the school work to find ways to engage in culturally sustaining practices, The Protector’s experiences reveal the shortcomings in these attempts and raise important questions that we explore in this article: What does it mean for school spaces and pedagogies to be culturally sustaining for Latinx students? How can the testimonios and experiences of Latinx students themselves drive curricular and institutional reform?

In this paper, we draw on the pluralistic concept of Latinidades to probe these questions and tease out possible ways toward achieving anti-hegemonic pluralism in schools. We argue that culturally sustaining education for Latinx students requires problematizing the boundaries of this term altogether, and making visible the tensions and multiple axes of oppression around what it means to be Latinx. We take inspiration from Latinx students—including one of the authors of this article, The Protector—who are challenging bounded notions of culture (such as “affinity groups”) and instead foregrounding questions about equitable practices in the day-to-day contexts of schools.

Coined by Django Paris (Alim & Paris, 2017) in response to decades of research on culturally responsive and relevant education, culturally sustaining pedagogy emphasizes the premise that education must be anti-hegemonic. When traditional schooling requires the homogeneity of students, it makes success in school a white assimilationist project that subsumes or eradicates the many cultures, languages, learning styles, epistemologies, and histories students represent. Instead, culturally sustaining pedagogy offers an alternative: that we sustain pluralism in education, without attempting to bridge an idea of a dominant culture. Yet, for Latinx students, homogeneity persists in the construction of a singular identity amid many intersecting experiences and social hierarchies. Making schools more culturally responsive and sustaining for Latinx students necessitates problematizing the boundaries of Latinidad and making visible the tensions around what it means to be Latinx, to exist within a category that is both state-imposed and claimed for the purpose of solidarity. By virtue of grouping people with different histories and levels of societal privilege and vulnerability, the Latinx category can also serve to erase and assimilate.

In 2019, New York State released its Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework. [3] Statewide policy support for anti-racist education is situated among complementary efforts in New York City championed by grassroots and youth organizers, and at times by the leadership of the New York City Department of Education itself. This political backdrop creates conditions for schools to design spaces for youth to feel comfortable and explore issues that pertain to their identities. But as The Protector’s experience as an in-betweener within her school’s affinity groups suggests, the translation of culturally sustaining education theory to practice and school structures must stay vigilant in not creating new hegemonic norms. We, the authors, have come together as part of an inquiry group reflecting on our lived experiences as Latinx individuals with Venezuelan, Dominican, Chicanx, and Argentinean backgrounds, and how our Latinx identities inform our roles as students, educators, and researchers. Saavedra and Pérez (2017) identify critical reflexivity as an extension of Gloria Anzaldúa’s approach to theory of the flesh, of the spirit, and of the land as a healing process from the lasting effects and inflictions of colonization. This approach requires writing from within, rather than writing about, with a focus on lived experience. Theorizing from within, we wrote and shared our testimonios, our stories that “highlight the power of lived experiences in the production of knowledge, emphasizing that knowledge arises from the body” (Saavedra, 2019, p. 179), to heal wounds and share love through dialogue, and to imagine a culturally sustaining education for, and more importantly, with, Latinx youth.

For this article, we center the testimonios of Ashantie, a high school senior in New York City, and the youngest and most implicated among us, to theorize the transformative power of in-betweenness. Grounded in the experiences she shares, we argue that, while equity work in schools can reify inequities by covering the pluralities and power dynamics of a singular Latinidad, educators can also embrace Latinidades as sites for enacting the pluralistic vision of culturally sustaining pedagogies.

Exerting White Dominance over Latinx Youth: One Hierarchy of Power

The Protector’s Testimonio #2: Language, Appropriation, and Cultural Wounds

I had a Spanish class, something I thought I would look forward to ’til a teacher threw a chancla at me and took my culture and did more than appropriate it. Thinking back now, she never really engaged with us. I sat in the back of the room with the other kids who already spoke Spanish. Most of the time we did busy work. We were kind of our own island. The day she threw the chancla happened so fast. All I remember was she threw it at me because I had my head down so she felt like I wasn’t paying attention but I was actually not feeling well. So, my reaction was I picked up the shoe and threw it back at her. I remember the sound of the shoe hitting the blackboard. At that moment I knew I let her get to me. I never reported the incident to anyone. I was hurt but thought to myself my all White administration is just going to reprimand her for throwing a shoe. What is the point? They won’t truly understand why I was actually hurt. I would’ve had to file a report then apologize for my behavior as well. I kept it in all these years until now. But that day the teacher created a sense of trauma. Trauma that would lead me to learning new terms like inequity, disparities, and culturally responsive teaching. What truly is culturally responsive education when half of the time teachers don’t acknowledge my identity?

The Protector was able to take a Spanish class, excited to learn in an academic setting the language of her family. Instead, she encountered a non-Latinx White teacher in the classroom, who, backed by a colonial legacy of domination, first appropriated her language and then used the cultural trope of throwing a chancla to hurt and humiliate her Dominican heritage. The message of the incident, embedded in layers of context (i.e., in school, in a Spanish class, with a teacher who was perpetuating whiteness, with Latinx Spanish-speaking students in the room who were not being engaged academically, and in an anti-Black and anti-Latinx sociopolitical climate), convey to The Protector that she does not belong in school except to be eradicated, where her language and culture can be stolen and weaponized against her. In his ethnographic study of a high school in Chicago and its Mexican American and Puerto Rican students, Rosa (2019) describes the circulation of deficit notions of bilingualism—even by the Latinx principal—that delegitimized students’ linguistic practices against the backdrop of white English-centered curricular norms. Rosa argues that languagelessness—the notion of bilingual students being characterized as not having a language, is a form of “linguistically argued racism” that was instituted in the school’s practices and policies and was inextricably linked to the racialization of the Latinx students in the school. The Protector’s Spanish class was a space where she thought she could explore her cultural and linguistic repertoires, the parts of herself that are not usually sanctioned in school. Instead, her teacher’s actions rendered her languageless at school while Spanish became yet another tool of oppression against her.

Even with the myriad educational initiatives aimed at supporting Latinx students, it is important to raise questions about which Latinx identities are being affirmed and which students continue to remain invisible under a white gaze or marginalized by the policies ostensibly implemented for their “benefit.” In both her affinity group exclusions (Testimonio #1) and the Spanish class chancla incident (Testimonio #2), The Protector experienced hegemonic violence in schools. Both of these incidents led her to ask, what does her school mean by culturally responsive education if in the spaces created for belonging, she did not belong? But there is an important distinction between the two events: in the Spanish class, The Protector was positioned negatively by the non-Latinx teacher and her classroom which reproduced white supremacy, while in the affinity groups, she was positioned negatively by her Black and Latinx peers, who had formed bounded groups that would serve to exclude her. These testimonios of The Protector, representative of the experiences of many Latinx youth, point to the need for culturally sustaining education to contend with vertical hierarchies between groups, and horizontal hierarchies within Latinx peoples (Aparicio, 2019).

Who is Latinx? Taking a Cue from Latinidades

Latinx Studies has been facing the tension between being Latinx and reifying coloniality, and we believe this transdisciplinary vantage point offers lessons for how schools can become more culturally sustaining—more attentive to the complexities, multiplicities, and contradictions of the “Latinx” category than its presumed homogeneity. Rather than thinking of Latinidad as a singular identity, Aparicio (2019) advances the term Latinidades to engage an anti-hegemonic framework for Latinidad:

The term Latinidades, then, allows us to document, analyze, and theorize the processes by which diverse Latina/os interact, subordinate, and transculturate each other while reaffirming the plural and heterogeneous sites that constitute Latinidad. Although we urgently need to analyze the vertical power differentials between the Anglo-dominant society and Latina/o racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities, particularly in the current political moment of Trump’s presidency and the state’s legitimation of white nationalist ideologies, we must also examine the horizontal differences, conflicts, tensions, and affinities between and among Latina/os of diverse national identities—what I propose as horizontal hierarchies (p. 31).

Latinidades, as opposed to the singular and narrow ways that being responsive to Latinx students comes to be codified in schools, entails reconceptualizing pluralism to include not only a vertical but also a horizontal analysis of social hierarchies. Individuals who self-identify as Latinx, including the four authors of this article, are all differently positioned around race, class, language, immigration status, and gender identities. Surface similarities mask consequential differences and historical oppressions. For example, differences in immigration histories—entangled with other identity markers such as race and class and languaging practices—are variously experienced by Latinx students. For Pamela, Lilly, and María Paula, being White Latinas allows us the privilege of not being subject to discriminatory practices that interpolate Latinx individuals through xenophobic and racist lenses. Some Latinx students and families experience economic and sociopolitical precarity more than others, and there is immense variability in the Latinx “category” from communities who work in the informal economy or who are targeted by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to social elites who have the financial resources and cultural capital to navigate schooling in the U.S. Even “migration” needs to be troubled, with the frequent back-and-forth between Caribbean contexts, like The Protector’s Dominican Republic, or the West and Southwest, where for Chicanx communities like Lilly’s, “the border crossed us” is a common refrain. Latin American contexts can be patriarchal and heterosexist, as well as reproducing coloniality through their marginalization of Indigenous and Black communities and their cultural and language practices (Anzaldúa, 2015).

School initiatives aimed at supporting Latinx students too often hinge on hegemonic forms of Latinidad that treat the Latinx category as one group, erasing these crucial differences across national identities, class, race, gender, language, and other social stratifiers (Aparicio, 2019). Even when we subscribe to the idea that we are all mixed (i.e., “mestizaje''), Latinidad is a homogenizing force that erases Afro-Latinx and Indigenous Latinx histories and experiences (Hernández, 2003; Saldaña-Portillo, 2017). Erasure can also happen in terms of language. The erasure of linguistic difference across Latinx peoples is yet another manifestation of colonial violence. This happens on the assumption that all Latinx people speak Spanish and in the erasure of Indigenous languages (Saldaña-Portillo, 2017) and the many Spanishes, Englishes, and hybrid languages Latinx youth speak. This brief list of (non-exhaustive) examples points to the complexities of enacting culturally sustaining education for Latinx students in order to attend to a broader array of equity issues. Emphasizing power asymmetries within the Latinx community turns us away from pedagogies premised on misguided assumptions about an “ideal” Latinx student and works to funnel resources so that they benefit Latinx communities who are made most vulnerable in the education system. We believe that making visible not only vertical inequities (e.g., Global North-Global South relations), but also horizontal hierarchies allows us to move beyond the unity/conflict narrative of Latinidad by creating spaces for critically engaging inter-Latinx dynamics (across identities) and intra-Latinx dynamics (within identities) (Aparicio, 2019); and by offering possibilities for working in solidarity towards addressing these inequities.

Anti-Hegemonic Latinidades as Transformative In-betweenness

Alim and Paris (2017) assert that as U.S. schools become increasingly diverse, education must sustain students’ cultural pluralism. First, cultures will need to be reclaimed and seen for their constant flux and renegotiation, careful not to essentialize or romanticize the past (Frantz Fanon as cited in Bhabha, 1994; Alim & Paris, 2017). Educators who subscribe to static ideas of culture, and singular categories like “Latinx” or “Hispanic” to encompass them, may perpetuate damaging stereotypes, shame students for not living up to what amount to cultural tropes, and even blame families for not teaching youth “their culture.” As such, the project of sustaining pluralism will require thinking beyond appearances of certain pedagogies, even those intended for educational equity. For example, a school may offer bilingual education, but do so in ways that privilege certain language varieties, and ultimately dishonor the many linguistic practices of students and their families. Static concepts of culture are homogenizing and, left unchallenged in reforms meant to be culturally affirming, will miss important distinctions among multiple intersections of identity.

We assert that Latinidades can offer a space for anti-hegemonic transformation, and for educators and students to learn what it means to sustain pluralism. Embracing a Latinidades framework entails seeing Latinx students as in-betweenners, both connected and disconnected from binary identity markers, fractured by colonial logics that would rather erase us than embrace us (Anzaldúa, 2015). In short, under a singular “Latinx,” we fall between the cracks, and worse, invest in the social hierarchies that will privilege some of us (e.g., light-skinned, heterosexual, cisgender, able-bodied, middle class) at the expense of others of us (e.g., dark-skinned, Indigenous, transgender, disabled, poor). Gloria Anzaldúa (2015) writes that when we confront the many intersecting social positions that fracture us, we have the opportunity to transform, and in that process:

It may be necessary to adopt some type of pan-ethnic term other than “latino” (given to us by mainstream media) or “Chicano/Latino” (cumbersome at best). To derive an appropriate pan-ethnic term we need to identify our common conditions and our different circumstances while honoring our diversity. (p. 74)

The Protector’s story of not belonging to either of the affinity groups at her school—of “living life as an in-betweener”—underscores the fissures of a Latinx struggle that involves reclaiming, rather than subsuming, pluralistic identities. Audre Lorde said, “It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.” While in-betweenness can mean falling through the cracks, it can also be where hope for something new begins (Freire, 1970/2017; Anzaldúa, 2015; Bhabha, 1994). If we take up in-betweenness as a cue to interrogate the ways we are differentially positioned, we can learn to sustain pluralism. For Latinx youth, critiques that arise from in-betweenness, from noticing injustices to leaning into studying those injustices, can mean taking the leap from passive receiver to agents of our lives and social transformations (Irizarry, 2017).

The Protector’s Testimonio #3: La rana que escapó el agua caliente

Being a queer Afro-Latinx student was hard enough, so imagine taking the role of The Protector. In the equity work I do, I spend a lot of my time observing. So imagine conducting walkthroughs and seeing all the Latinx students sitting in the back of the classroom in a group. Where they knew the White teacher would hardly pick on them and when the teacher does, she says, “You can associate words like sphere back to your own language” and you think to yourself, “Wow, so helpful” ’til she picks on one of the few Latinx kids in the room and says, “Isn’t this how you say sphere in Spanish? Esfera.” Seeing those kids in the back of the room reminded me of the time I was in the back of the room not feeling seen. The only time being acknowledged was because the teacher was trying to be culturally responsive but failed at it. Now, as an observer, I had to excuse myself from the room because this is why we see more and more Latinx students lose interest in school.

The Protector’s favorite author, Audre Lorde, said in a 1979 feminist conference where she felt tokenized as a Black woman, “For the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change” (Lorde, 1984/2007, p. 112). Similar to what Lorde experienced, The Protector noticed that some teachers at her school only call on Latinx students for shallow and tokenizing participation that did not engage their existing linguistic repertoires, while substantive participation is catered to and reserved for other students. When her stomach churned with the discomfort of injustice, The Protector left the room. Rather than passive acceptance of injustice throughout her education, The Protector decided to act on it. Despite some bad experiences at her school, The Protector’s show of agency when confronted with her in-betweenness did not go unnoticed. At the behest of one of her “soccer moms,” (her nickname for two teachers who have forged genuine, caring relationships with her), The Protector became involved in Students and Educators for Equity, a youth-adult partnership between the NYC Department of Education, the NYU Metro Center, and high school youth in schools across the city working on uprooting racial disproportionality from within. Through this program, she conducts mixed-methods research on how students feel about their school and what they want from their school, while analyzing the data to understand whether and how students experience racial disproportionality. Her research praxis has led to positive results for her school: more teachers and administrators trained in restorative justice, the formation of peer mediation groups, added sections of AP classes and SAT prep for students to address racial opportunity gaps at her school, and bringing drag culture and Pride Week to a middle school also working with Students and Educators for Equity. Engaging in social transformation work means leaning into what falls between the cracks, and as The Protector began to interrogate her own in-betweenness with other students, she was able to have agency over her situation and to forge paths toward educational equity in her school.

The Protector’s Testimonio #4: In change, I matter

The first time I noticed real change in my school was later in my Spanish 3 class, with my favorite orgullosa Latinx teacher. Let me tell you, Profe is probably one of the best Spanish teachers I’ve ever had. We watched movies on famous Latinx people like Selena and Hector Lavoe. Something I love is my cultura. So imagine when you step into class and the objective of the day is on your community. She created a week's worth of PowerPoints on the Afro-Latinx community. Something I thought would never get to see ’til I got to college. I remember suddenly feeling like I was enough and in my space. Funny thing is it wasn’t a space that was created based off of what a box said I am. All I can remember was looking at Profe and wanting to tell her thank you for making me and my people matter. All it takes is a simple acknowledgment of our differences and at the moment a sense of healing was created.

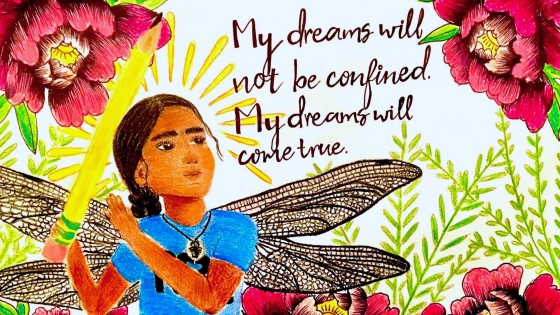

What matters to The Protector is not the Spanish subject. In and of itself, Spanish cannot be culturally sustaining, as her disparate experiences with this subject exemplify. What The Protector wants, what Ashantie wants, is to be seen for who she is and to be free to be fully herself in school. When The Protector began to experience for herself more humanizing educational spaces within her school, she partially attributed it to the student-led equity work she was engaging in, whereby she was able to inquire into her observations of school injustices, link her experiences to the perspectives of others, and help create plans to bring about change. Still, it does not escape her that as time goes by in her high school career, she has collected cariño from more of her teachers, like her soccer moms, whose individual actions eventually have woven together an indispensable web of love and support. She represents these teachers in her drawing (Figure 1); they are the hands that prop her up in healing from her in-betweenness. While The Protector feels teachers who see her and uplift her are invaluable, she still represents herself in a box because beyond individual teachers, broader systemic change is still needed to shift the school culture to be more culturally sustaining and to dismantle the categories and assumptions imposed on students.

Living in the space between identity categories means we have the power to cross barriers and boundaries, but not through ideas of “mestizaje” that end up being anti-Black (Hernández, 2003) and vanishing Latinx Indigeneities (Saldaña-Portillo, 2017). Cultures do not exist in bubbles, and when we try to name cultures as monolithic, we are enacting colonial logics that obscure differences. The official language of education often treats cultures in bounded ways that both homogenize and divide (e.g., a new initiative is for “Black and Latinx students,” as if these groups were as simple as two separately homogenous identities). Latinidades offers room to redefine our personhoods, and to demand and create school spaces that love our hybridities and pluralism. Interrogating the in-betweenness of being Latinx can mean the difference between sustaining pluralism and reifying racism, classism, and other manifestations of hegemony. In-betweenness is where young people can locate their pluralities and transformational brilliance, and where adults can follow their lead to a culturally sustaining education.

[1] To freely use our full linguistic repertoires as writers, we chose not to italicize Spanish words, as would be the convention under APA guidelines. Instead, we center our multilingualism and translanguaging practices in this piece by putting English and Spanish on an equal plane. We recommend this video by Daniel José Older to learn more about our stance on not italicizing non-English words.

[2] “Hey, old man!”

[3] http://www.nysed.gov/bilingual-ed/culturally-responsive-sustaining-education-framework

References

Alim, H. S., & Paris, D. (2017). What is Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy and Why Does It Matter? In Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World (pp. 1–21). Teachers College Press.

Anzaldúa, G. E. (2015). Light in the Dark/Luz en lo oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality (A. Keating, Ed.). Duke University Press.

Aparicio, F. R. (2019). Horizontal Hierarchies: The Transnational Tensions of Latinidad. In Negotiating Latinidad: Intralatina/o Lives in Chicago (pp. 27–43). University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.5406/j.ctvqc6h6r

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture. Routledge.

Freire, P. (1970/2017). Pedagogy of the Oppressed (50th Anniversary). Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.

Hernández, T. K. (2003). ‘Too Black to be Latino/a:’ Blackness and Blacks as Foreigners in Latino Studies. Latino Studies, 1(1), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.lst.8600011

Irizarry, J. G. (2017). “For Us, By Us”: A Vision for Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies Forwarded by Latinx Youth. In D. Paris & H. S. Alim (Eds.), Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Social Justice in a Changing World (pp. 83–98). Teacher College Press.

Lorde, A. (1984/2007). Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press.

Rosa, J. (2019). Looking Like a Language, Sounding Like a Race: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Learning of Latinidad. Oxford University Press.

Saldaña-Portillo, M. J. (2017). Critical Latinx Indigeneities: A paradigm drift. Latino Studies, 15(2), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-017-0059-x

Saavedra, C. M. (2019). Inviting and Valuing Children’s Knowledge through Testimonios: Centering “Literacies from Within” in the Language Arts Curriculum. Language Arts, 96(3), 5.

Saavedra, C. M., & Pérez, M. S. (2017). Chicana/Latina Feminist Critical Qualitative Inquiry: Meditations on Global Solidarity, Spirituality, and the Land. International Review of Qualitative Research, 10(4), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2017.10.4.450

Bios:

Pamela D’Andrea Martínez is a PhD candidate in Urban Education at New York University, researcher at NYU Metro Center, adjunct professor of Teaching and Learning, and a former public school teacher. Her research interests include antiracism in schools and equitable education for newcomers. She can be reached via email at pdm322@nyu.edu.

Ashantie Diaz Johnson is an undergraduate student at St. Francis College. Her research focuses on culturally responsive education. She can be reached via email at ajohnson10@sfc.edu

Lilly Padía is a PhD student and graduate research assistant in Teaching and Learning--Special Education at New York University, adjunct lecturer and graduate advisor in Bilingual and TESOL programs at the City College of New York, CUNY. Her research focuses on the intersections of special education, bilingual education, and culturally sustaining pedagogies. She can be reached at lilly.padia@nyu.edu.

María Paula Ghiso is an Associate Professor of Literacy Education in the Department of Curriculum and Teaching at Teachers College, Columbia University. She can be reached via email at mpg2134@tc.columbia.edu.