The article examines the experiences of Black and Latinx families across New York City to explore routes to prevention of cultural displacement as City schools undergo seismic demographic shifts as a result of gentrification. Diana Cordova concludes that we need racially just policies and research designed to truly integrate and stabilize racially and ethnically diverse schools.

Lessons from Gentrification for Integration in a Changing Racial/Ethnic Context

By Diana Cordova-Cobo

In the fall of 2015, I sat across from Rosa Chavez at a coffee shop near her daughter’s public elementary school. For two hours, she recounted her experience growing up in the surrounding neighborhood and attending the same school her daughter now attends. The stories she focused upon most intently were those of the residents in the school facing displacement, and the ways in which her school community and her neighborhood were changing as a result. She outlined the work done during the past school year to re-establish a Latinx parent voice in the school after a shift to a white, mostly-affluent Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) left several parents feeling as though they could no longer contribute in ways they once did. Battles raged over seemingly small decisions such as moving away from the local Puerto Rican DJ for the school dance or discouraging Abuelita's cooking because it did not meet healthy eating standards. All these seemingly minor events added up to a drop in attendance at PTA meetings on the part of previously active Latinx families. Rosa’s anecdotes, heartbreaking as they were, ultimately followed the same narrative as other parents with whom the Public Good research team spoke with between 2015 and 2017.1 Every interview was a web of stories about PTAs, school events, and mixed feelings about all the shifts parents were seeing in their neighborhoods and schools.

Though compelling, the experiences of these parents did not match up to the larger public narrative about the relationship between residential gentrification and school demographics at the time. According to a majority of journalists and researchers, gentrifiers were not enrolling their children in public schools. Capturing this sentiment, Hannah-Jones (2015) stated, “Gentrification, it turns out, usually stops at the schoolhouse door.” This mismatch between what I heard from parents about the changing racial/ethnic dynamics of their school communities and what I saw reflected in academic research and popular press media ultimately motivated much of the research I have done since that time. I find myself returning to this question: How can we learn from the experiences of Black and Latinx families across New York City to ensure we are proactively preventing cultural displacement as schools continue to experience changes through a variety of demographic phenomena? In the following discussion, I outline how we can draw from these experiences to better design research and policies aimed at creating integrated school communities through intentional school-level practices.

Cultural Displacement:

When Demographic Change Means Losing Representation

Along with residential and school gentrification has come an increased concern over displacement—the process whereby existing residents are increasingly pushed out and priced out of the neighborhood. Despite early observations about displacement (Glass, 1964), the research on residential gentrification has yet to come to consensus on what should be defined as displacement. Some researchers argue that various forms of displacement result from gentrification with a focus on longtime community members (Atkinson, 2000; Davidson & Lees, 2010; Newman & Wyly, 2006) and others suggest that more affluent newcomers bring resources to poor communities, creating positive neighborhood effects with little or no displacement (Ellen & O’Regan, 2011; Freeman, 2005, 2008; Freeman & Braconi, 2004; Vigdor, et al., 2002). On the other hand, in research on school gentrification, the direct impact of a growing white, affluent school population on existing families of color and low-income families has been central. This qualitative research overwhelmingly points to a change in power dynamics that may negatively impact families of color and low-income families (Cucchiara and Horvat, 2014; Cucchiara, 2013; Muro, 2016; Stillman, 2011; Posey-Maddox, 2012; Posey-Maddox, 2014; Roda and Wells, 2013).

Though research details the impact of gentrification on the existing school community, few studies focus on the experiences of low-income families and families of color. Overwhelmingly, the discussion is centered on the actions of white, affluent gentrifiers—the body of research focuses on who comes into the school instead of who leaves. Focusing on displacement at the school level reframes the conversation around the experiences of families of color and low-income families who are leaving the schools completely or simply exiting community spaces and spaces of power within their schools.

The anecdotes about the day-to-day interactions between families from different racial/ethnic backgrounds and the underrepresentation of Latinx and Black parents in the decision-making processes that Rosa and other parents described constitutes a form of displacement. Marcuse (1985) began advocating over thirty years ago for a framework that captured the indirect forms of displacement that longtime residents could experience during gentrification. One of the ways residents experience indirect displacement is through “the pressure of displacement,” which he describes as:

When a family sees the neighborhood around it changing dramatically, when their friends are leaving the neighborhood, when the stores they patronize are liquidating and new stores for other clientele are taking their places, and when changes in public facilities, in transportation patterns, and in support services all clearly are making the area less and less livable, then the pressure of displacement already is severe. Its actuality is only a matter of time. Families living under these circumstances may move as soon as they can, rather than wait for the inevitable; nonetheless, they are displaced. (p.207)

Cultural displacement, as an indirect form of displacement, involves the loss of place and belonging at the school level that ensues when residents start seeing their school community transform in front of them. Even if parents are able to keep their children enrolled in a school, “gentrification is experienced as a loss of self, community and culture” (Cahill, 2007). Most of the parents we interviewed were not physically displaced, yet they still expressed a sense of loss as they described their neighborhoods and schools changing around them. Mirroring Muro’s (2016) findings on symbolic integration, more often than not interactions between gentrifying parents and the existing parent community were pleasant but resulted in a white parent “takeover” of the PTA. This, in turn, left Black and Latinx families feeling undervalued and disenfranchised in the school community.

Mapping to Understand the Extent of Demographic Change Across New York City’s Elementary Schools

While doing qualitative research on gentrifying schools, it became apparent that part of why the phenomenon parents described was under-accounted for in research on New York City’s schools was that researchers were overwhelmingly focused on identifying schools by a shift in their overall racial/ethnic composition over time when compared to other schools. However, what most Black and Latinx parents described during interviews was the process of gentrifying—meaning there was a recent influx of more affluent, mostly white parents that was already having an impact on the entire school community. The gentrifying families were not yet distributed across all grades evenly and were heavily concentrated in the youngest grades. Rosa recounted one PTA meeting after another at which she grew frustrated with the board because so much of the extra programming for students funded by the PTA was being reserved for the youngest grades. The reality of this has been documented at length across the country. In sum, it takes a relatively small number of white and/or affluent parents with social and economic capital to shift the power dynamics in a public school in a way that marginalizes lower-income families and families of color (Cucchiara and Horvat, 2014; Cucchiara, 2013; Posey-Maddox, 2012; Posey-Maddox, 2014).

As important as the experiences of families in New York City’s schools are on their own, it is also important to understand the extent to which the experiences described by parents represented a pattern across the city during and whether this phenomenon was concentrated in certain areas of the city. Understanding if and where these changes in student demographics are taking place has important implications for proactively designing policies and practices in schools that serve to prevent the marginalization and disenfranchisement Rosa and other parents felt as their school communities changed.

With this in mind, I set out to understand if there were more areas of the City where multiple schools were gentrifying along racial/ethnic lines in particular because this is how parents characterized school gentrification in interviews. Using data from the National Center of Education Statistics (NCES) for the 2014-15 school year, I employed a spatial cluster analysis technique to understand the distribution of within-school demographic change for Black, Latinx, Asian, and white students in New York City’s public elementary schools. I focused on within-school change. Limiting my sample to public, non-charter schools that had both a kindergarten and fifth grade during the 2014-15 school year (n=716), I calculated the percentage point difference between the fifth grade and kindergarten for each racial/ethnic group’s share of the student population. Essentially, if researchers had only looked at the overall school racial/ethnic composition instead of differences between grades within the same school, there was a chance the phenomenon was being dulled by the fact that a shift in a racial/ethnic composition had not occurred in all grade levels yet.

Furthermore, focusing on schools where the racial/ethnic composition was substantially different between the youngest and oldest grades provided two important insights. First, it identified areas of the city that were on the frontline with respect to navigating complicated racial/ethnic dynamics at the school level as demographics shifted. Second, this focus allowed a better understanding of how changes varied by racial/ethnic group. I was especially interested in detangling the white/nonwhite binary as a way of understanding gentrification—and demographic change writ-large—in New York City’s public schools.

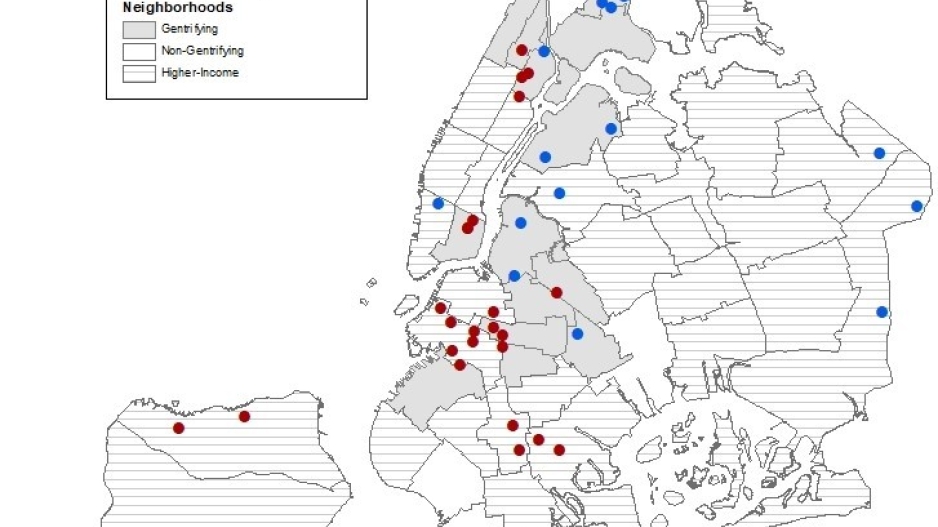

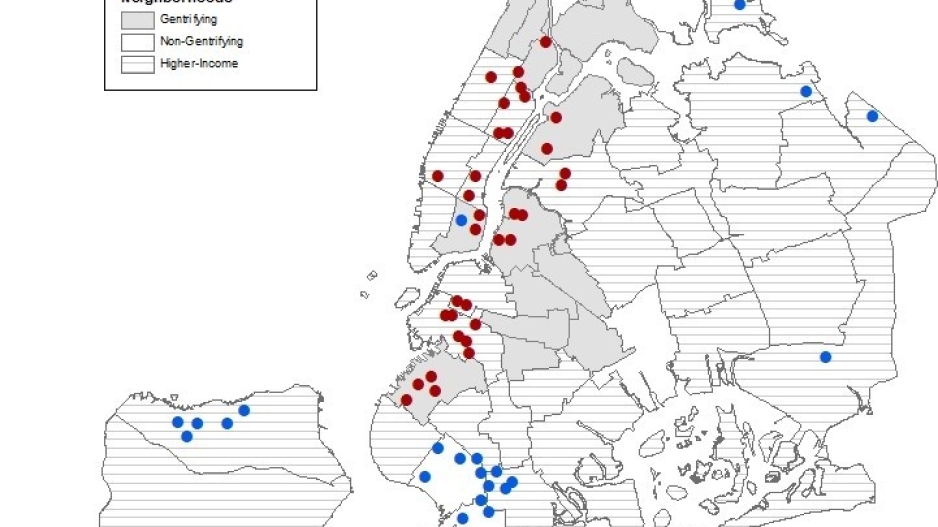

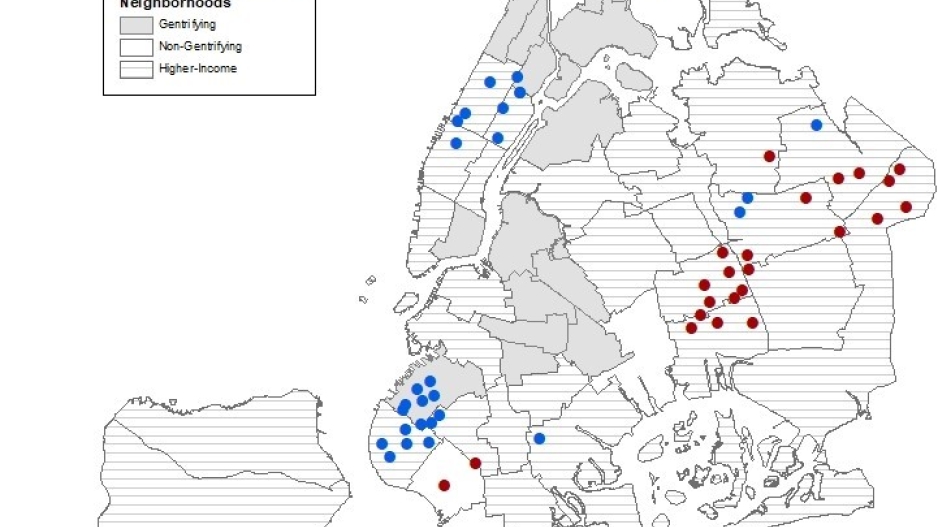

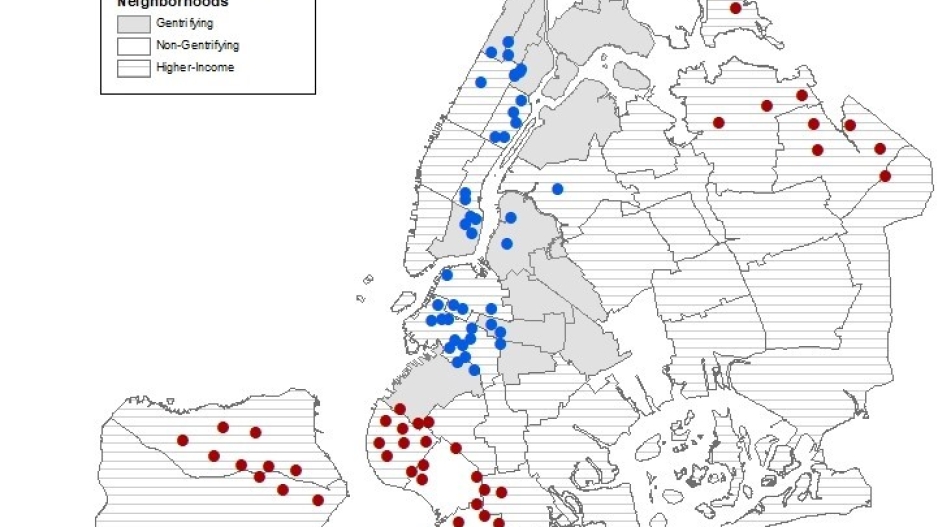

Once the data were mapped out, early observations hinted at a spatial pattern of unequal distributions of demographic change. Though the citywide averages for racial/ethnic percentage point differences between fifth grade and kindergarten ranged from a loss of 2.3 percentage points for the Black student population to a gain of 1.1 percentage points for the White student population, some schools experienced more dramatic differences. Seeing some indication of spatial patterns, I conducted a significant cluster analysis, which measures if there are geographic areas within the city where there is enough of the same phenomenon happening to show the statistical spatial significance for groups of schools. Figures 1-4 show clusters of schools that are experiencing spatially significant demographic change—defined as a percentage point difference in the share of students from a racial/ethnic group between kindergarten and fifth grade- for each racial/ethnic group. For contextual understanding, neighborhood boundaries and the NYU Furman Center’s neighborhood gentrification classifications are layered behind the clusters.2

These analyses indicate that some significant changes are happening within each racial/ethnic student category. For the Black student population, there is not as clear of a spatial pattern in terms of inner and outer city boundaries (Figure 1). But certain neighborhoods that are frequently discussed in the debate over gentrification and were identified as gentrifying in 2015 by the NYU Furman Center—such as Bedford-Stuyvesant and East Harlem—show significant clusters of schools with smaller shares of students who were Black in kindergarten than in fifth grade. For the Latinx student population, there were clear patterns in the school data that reflect both the narratives of parents in New York City and the qualitative research on residential gentrification (Figure 2). Clusters of schools with a smaller share of Latinx students in kindergarten than in fifth grade are mostly concentrated in the center of the city while clusters of schools with greater shares in kindergarten are concentrated in the outer rims. Additionally, schools with smaller shares of Latinx students in kindergarten than in fifth grade were located in neighborhoods such as the Lower East Side, Sunset Park, and Williamsburg that were identified as gentrifying by the NYU Furman Center.

The clusters of schools with a smaller share of students who were Asian in kindergarten than in fifth grade are mostly on the outer, eastern rims of the city in Queens and the clusters of schools with greater shares in kindergarten are almost entirely in the western section of Brooklyn or Manhattan (Figure 3). A similar pattern holds for the white student population, though more clearly spatially concentrated (Figure 4). Clusters of schools with greater shares of students who were white in kindergarten are exclusively concentrated in Manhattan and the parts of Brooklyn and Queens closest to Manhattan – including neighborhoods identified as gentrifying in 2015 and neighborhoods frequently described as gentrified or “hyper-gentrified” in the larger public debate over gentrification. Additionally, several of the schools with greater shares of students who were white in kindergarten also overlap with schools that had smaller shares of students who were Latinx or Black in kindergarten.

Figure 1. Clusters of Public Elementary Schools with a Difference in the Share of Black Students between Kindergarten and Fifth Grade, 2014-15

Figure 2. Clusters of Public Elementary Schools with a Difference in the Share of Latinx Students between Kindergarten and Fifth Grade, 2014-15

Figure 3. Clusters of Public Elementary Schools with a Difference in the Share of Asian Students between Kindergarten and Fifth Grade, 2014-15

Figure 4. Clusters of Public Elementary Schools with a Difference in the Share of White Students between Kindergarten and Fifth Grade, 2014-15

This initial analysis revealed that the patterns of Latinx, Asian, and white demographic change for percentage point differences between kindergarten and fifth-grade shares follow the patterns in residential and qualitative research findings. Though the cluster groups for the Black student population showed no immediate spatial pattern, a general pattern of loss is in line with the larger citywide demographic trends where the share of students who were Black in public, non-charter schools has steadily declined in recent years. Therefore, this small adjustment in how we define the demographic change in the school data – informed by the experiences of families across the city—revealed that the experiences of Black and Latinx parents in a handful of schools spoke to a much larger phenomenon. I argue that this phenomenon suggests that their experiences should be centered in the larger discussion on school gentrification (and integration). Though there is a further investigation to be done regarding the relationship between these school patterns and residential shifts in the city along racial/ethnic and socioeconomic class lines, these findings suggest there are broader implications of this work. Specifically, given the extent of these patterns, we must consider how practices and policies can be proactively implemented across the city to subvert some of the negative impacts of demographic shifts that were highlighted by parents like Rosa in schools seeing an influx of more affluent and/or white students.

Combatting Cultural Displacement with Affirming Leadership and Intentional Structures

Despite fear or cynicism for what an influx of white, more affluent families would mean for their own power and voice within their schools, Black and Latinx parents do see benefits of additional racial/ethnic and socioeconomic diversity for their children. The desire to maintain “diversity without displacement” was overwhelmingly evident. This sentiment among parents and community members has implications in any changing racial/ethnic context. While the sociopolitical dynamics that underlie the beginning stages of gentrification and integration differ, they both fundamentally represent a change in the racial/ethnic dynamics of a school community. How school leaders and families navigate the changing dynamics has implications for whether the change in racial/ethnic demographics results in the gentrification or the integration of the school community.

In many ways, policies and practices aimed at preventing the cultural displacement experienced by Rosa and other parents also serve the goals of true integration. Carter (2015) defines true integration as “deep intercultural exchanges in learning where no group is on the margins…. Integration weakens thick social boundaries and fosters empathy among people of varied social backgrounds as they teach, learn, communicate, and interact within a school community in ways that till the soils of a burgeoning democracy.” Though Carter articulates this as part of her focus on student learning, the same principles can live in the interactions between parents and families within a school community. To this end, two key factors arose while speaking with Black and Latinx parents that are needed to foster integration over gentrification: Affirming School Leadership and Intentional Parent Engagement Structures.

Parents overwhelmingly pointed to the importance of school leadership in counteracting the cultural displacement they witnessed in other schools throughout the district and the city.

School-level leadership—more so than district and citywide administrations—can directly influence the day-to-day interactions between different racial/ethnic groups. Black and Latinx parents described the ways in which the school administration systematically ensured that the voices of the incoming white, more affluent parents did not overshadow the existing Black and Latinx parents at the school. Several parents and staff members noted the racially-balanced approach to parent leadership and the explicit discussions the school had if it appeared that representation was not balanced along racial/ethnic lines. The same was true for other positions on the PTA board and for other school activities that required parent leadership such as the School Leadership Team and open houses. Parent coordinators even did intentional recruiting along with members of the PTA board if they felt like certain groups of families were not being represented. Though these efforts were not always successful in immediately achieving balanced representation on parent leadership teams, many Black and Latinx parents expressed a renewed hope that their voice was being valued and reinstated in the school community- particularly in schools that experienced periods of turmoil and tension between different racial/ethnic groups.

Additionally, there was overwhelming evidence that the administration’s messaging, which placed emphasis on the value of the existing school community before gentrification, served to simultaneously affirm the value of parents of color in the school as well as mitigate white, affluent parents who tried to enroll in the school under the assumption that they could “buy” the privileges they wished their children to have within the school or “help” the school “get better.” Some school leaders also opted to address gentrifying parents individually to address the implicit biases prospective parents had coming into the school.

While these school communities fight an uphill battle against the larger structural forces that are contributing to the physical displacement of their student population via housing instability and school choice, we observed success in mitigating the impact of cultural displacement for Black and Latinx parents in schools where leadership and staff took an asset-based approach to incorporating their voices in parent leadership structures. Instead of feeling as though their schools perpetuate the same disenfranchisement they witness with residential gentrification in their neighborhoods, explicit and intentional efforts to combat cultural displacement allowed parents to view their schools as a “safe place” where they could ensure that the needs of their children and families would not be overlooked in service of gentrifying parents with more political and economic clout.

Finding ways to mediate parent and student relationships across racial/ethnic and class lines in ways that mirror and expand the aforementioned efforts should be at the forefront of the concerns that policymakers and researchers are addressing if the aim is to truly integrate and stabilize racially/ethnically diverse schools.

Notes

1. The Public Good project is a public school support organization that uses research to engage racially and culturally diverse school communities in facing power dynamics and difficult issues, while amplifying voices as needed to create a truly integrated and inclusive public school.https://www.tc.columbia.edu/thepublicgood/.

2. NYU Furman Center. “Focus on Gentrification” in State of the City’s Housing and Neighborhoods 2015. (2016). The NYU Furman Center established these classifications using the 1990 Census and the American Community Survey (ACS) 2010-2014 five-year estimates. Neighborhoods are defined by sub-borough areas. “Gentrifying neighborhoods” are neighborhoods that were low-income in 1990 and experienced rent growth above the median neighborhood rent growth between 1990 and 2014. “Non-gentrifying neighborhoods” are those that also started off as low-income in 1990 but experienced more modest rent growth. Higher-income neighborhoods” are neighborhoods that were in the top 60 percent of the 1990 neighborhood income distribution.http://furmancenter.org/research/sonychan/2015-report.

References

Atkinson, R. (2000). The hidden costs of gentrification: Displacement in central London. Journal of housing and the built environment, 15(4), 307-326.

Cahill, C. (2007). Negotiating grit and glamour: young women of color and the gentrification of the lower east side. City & Society, 19(2), 202-231.

Carter, P. L. (2015). Educational equity demands empathy. Contexts, 14(4), 76-78.

Cucchiara, M. B. (2013). Marketing schools, marketing cities: Who wins and who loses when schools become urban amenities. University of Chicago Press.

Cucchiara, M. B., & Horvat, E. M. (2014). Choosing selves: The salience of parental identity in the school choice process. Journal of Education Policy, 29(4), 486-509.

Davidson, M., & Lees, L. (2010). New‐build gentrification: its histories, trajectories, and critical geographies. Population, Space and Place, 16(5), 395-411.

Ellen, I. G., & O’Regan, K. M. (2011). How low income neighborhoods change: Entry, exit, and enhancement. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 41(2), 89-97.

Freeman, L. (2005). Displacement or succession? Residential mobility in gentrifying neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Review, 40(4), 463-491.

Freeman, L. (2008). Comment on ‘The eviction of critical perspectives from gentrification research’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(1), 186-191.

Freeman, L., & Braconi, F. (2004). Gentrification and displacement New York City in the 1990s. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(1), 39-52.

Glass, R. (1964) London: Aspects of Change. Centre for Urban Studies: London, England.

Hannah-Jones, N. (February 2015). “Gentrification doesn’t fix inner city schools”. This Grist. Retrieved fromhttp://grist.org/cities/gentrification-doesn’t-fix-inner-city-schools/

Marcuse, P. (1985). Gentrification, abandonment, and displacement: Connections, causes, and policy responses in New York City. Wash. UJ Urb. & Contemp. L., 28, 195.

Muro, J. A. (2016). “Oil and Water”? Latino-white Relations and Symbolic Integration in a Changing California. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 2(4), 516-530.

Newman, K., & Wyly, E. K. (2006). The right to stay put, revisited: gentrification and resistance to displacement in New York City. Urban Studies, 43(1), 23-57.

Posey, L. (2012). Middle-and Upper-Middle-Class Parent Action for Urban Public Schools: Promise or Paradox?. Teachers College Record, 114(1), n1.

Posey-Maddox, L. (2014). When middle-class parents choose urban schools: Class, race, and the challenge of equity in public education. University of Chicago Press.

Roda, A, and Wells, A. (2013) ‘‘School Choice Policies and Racial Segregation: Where White Parents’ Good Intentions, Anxiety, and Privilege Collide.’’ American Journal of Education 119:261–93.

Stillman, J. B. (2011). Tipping in: School integration in gentrifying neighborhoods (Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University).

Vigdor, J. L., Massey, D. S., & Rivlin, A. M. (2002). Does gentrification harm the poor? [with Comments]. Brookings-Wharton papers on urban affairs, 133-182.

Diana Cordova-Cobo is a doctoral candidate at Teachers College Columbia University and research associate for the Center for Understanding Race and Education.